CHAPTER I – INTRODUCTION

This paper outlines the need for a new model of strategic analysis of non-state actors, in the context of foreign security policy. Through careful analysis of the existing literature and theoretical frameworks. I demonstrate the validity of strategic identity as a concept and hypothesise that through the blending of narrative analysis and strategic culture analysis, a strategic identity analysis of a strategic actor can be conducted. A strategic actor is any actor with strategic aims and objectives, there is no condition for a strategic actor to be a state and this model is produced in a neutral way to apply equally to state and non-state actors. To illustrate this, I use the terrorist organisation Daesh as a case study. Also known as ISIS/ISIL, Daesh is an anglicised abbreviation of the organisation’s Arabic name, al-Dawlah al-Islamiyah fil-Iraq wa-al-Sham (Irshaid, F, 2015); it is used here because it is closer to the narrative put forward by the organisation themselves and so is more appropriate for use when trying to ascertain and analyse the strategic identity of the group. Because narratives are the way in which we define ourselves and other entities and express the way in which we experience events (Ochs and Capps, 1996 p21), it is important to pay close attention to the language used by the actor in construction of their own narratives.

This first chapter introduces the key concepts and literary works relied upon in the construction of the model. My hypothesis is introduced and then the theoretical landscape is established, first with a brief discussion of strategic culture analysis in point, then with a brief description of narrative analysis in point before finally introducing my model for strategic identity analysis in point. Chapter II explores some of the existing theory and explains first the strengths and short comings of strategic culture analysis point, then the strengths and weaknesses of narrative analysis before introducing strategic identity analysis as a bridge between the two areas. Ultimately strategic identity analysis is the blending of a positivist and a post positivist approach in an attempt to achieve a binocular perspective. Positivist approaches strive towards mathematical or scientific proof. Post positivists would argue that this approach to a social science is impractical because observation is fallible. By softening the rigour applied to the positivist model of strategic culture analysis whilst adhering to a codified and repeatable model with simple steps, a compromise can be achieved which allows for repeatable tests whilst also recognising the imprecise equivocal nature of the data being analysed. This is the knowledge gap in which strategic identity analysis takes root.

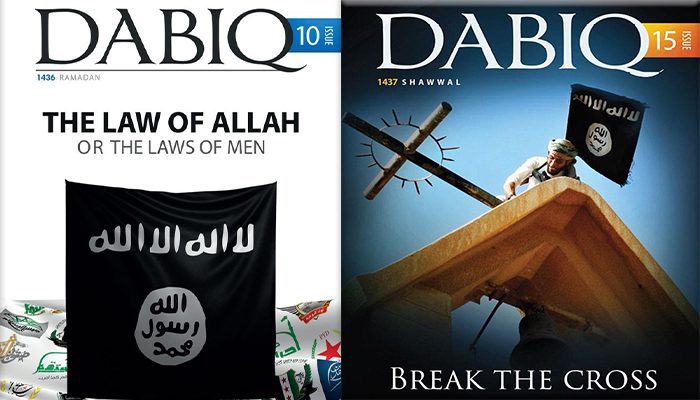

Chapter III of this paper is the case study. The model which is developed and justified in chapter II is applied to the context of Daesh using issues 8-10 of Dabiq. The case study is effectively a short strategic identity analysis to demonstrate the efficacy of the model. The paper concludes with a reiteration of the hypothesis, a summation of the methodological pedigree of strategic identity analysis and a brief discussion of the way in which the case study supports the creation of the model before suggesting future areas of development to the model.

Hypothesis

Strategic culture analysis is not applicable to non-state actors such as the terrorist organisation, Daesh, because it is a state centric model. Narrative analysis shares its disciplinary roots with strategic culture analysis, in Security Studies and International Relations, as such, the blending of the two fields to produce a hybrid model is to the overall benefit of the discipline. The amalgam of positivist and post positivist approaches removes dogmatic dedication to empiricism by allowing qualitative data and identity to be considered alongside empirically observable truths in a clearly defined framework for analysis so that tests can be repeated and the model applied to other case studies. This affords the academic a unique binocular view of the problem and as such, reduces the likelihood of such works falling foul of the archetypal criticisms associated with each approach. By allowing strategic culture analysis to evolve into the twenty-first century to face twenty-first century issues, the oxymoronic relationship between the scientific precision purported by strategic culture analysis, and the nature of assumptions is overcome through careful and reasoned examination of the narratives produced by the organisation themselves. The primary pitfall of parsimony, namely that actors are human beings and therefore inherently complex creatures; the intricacies of which may be lost in the process of distilling data to its most simplistic and base form, can be mitigated through blending in post-positivist thinking. Likewise, the oft cited criticism of narrative analysis and other post-positivist approaches, that they fail to approach even pseudo-scientific standards of analysis, can be overcome by blending the rigorous three-pronged model of strategic culture analysis. This blended approach is strategic identity analysis.

Introduction to Strategic Culture

Strategic Culture as defined by Gray (1981, p22) is based on the perceptions of the historical experience of a state referring to modes of thought with regard to the use of force. Whilst Gray does not explicitly use the term state, the definition was written to analyse the USSR on the assumption that the state was the appropriate unit for analysis. Subsequent attempts by strategists and academics to reapply this definition to non-state actors such as Al Qa’idah have been limited because the epistemological roots of the study are still confined within the construct of a global society of states. If we want to consider non-state actors as a referent object, then it stands to reason that a new model is required. There are four criteria for statehood as established in article one of the Montevideo Convention (Montevideo Convention, 1933–1936). A state must have;

- A defined territory

- A permanent population

- A system of governance

- The capacity to enter into relations with other states

The state seems an appropriate unit for analysis given that in conventional western discourse, the state has a monopoly on the use of force as proposed by Hobbes (Hobbes, 2005). However, in recent years we have seen a disciplinary shift within International Relations to consider the importance of the individual as a political actor. Furthermore, there has been a shift post Cold War, towards asymmetric conflicts between states and non-state actors. In light of these developments, it is archaic to limit strategic study to state centric models. We are instead, better served by focussing on nations than states.

In the globalised world, people are able to travel and communicate across the planet with relative ease. The notion of nations as being a term limited to groups sharing historical, ethnic or cultural heritage and territory is outdated; as evidenced by ever increasing migration patterns and the increased ease of global communication. Indeed as Tsagarousianou argued, with the rise of social media, a nation of people can be physically diasporic while being consolidated in the shared virtual space which they inhabit (Tsagarousianou, 2004). Therefore, in the modern world, nations are better thought of as divorced from the soil which they may occupy, and instead of being defined geographically, they should be thought of simply as groups of people with a collective cultural, historical, religious, ideological or ethnic identity.

This paper will attempt to build on the work of later Strategic Culture theorists such as Johnston and Narrative Analysis theorists such as Bruner and Reissman to, using the context of Daesh as a case study, provide a model which is tailored for use when analysing the strategic identity of non-state militant groups.

Strategic Identity Analysis

I define strategic identity as an identity, constructed by a strategic actor through narratives and normative assertions encompassing shared history and religious assumptions, and relating to conflict, the framing of adversaries and the perception of force.

I hypothesise that since all actors construct an identity, all strategic actors will therefore have a strategic identity. Because of the growing evolution of conflict leading to a shift towards asymmetric conflicts between state and non-state actors rather than traditional conventional inter-state war, it is important that International Relations continues to evolve in line with the real world. International Relations as a discipline was started as a normative study to prevent war and establish peace. Given that to date, all wars and asymmetric conflicts have ended in some form of negotiation (Wallensteen, 2015), this paper seeks to provide a framework which academics can use to dispel misconceptions about actors and in so doing, allow those actors to become relatable and therefore open the pathways to negotiation and peace.

Methodology

Building upon the work of existing Strategic Culture Analysis Theorists, I will use the model provided by Johnston (Johnston, 1995) which depends on three assumptions. The first of Johnston’s (Johnston, 1995 p46-47) assumptions is the frequency of war in human affairs. The second assumption, is the nature of the adversary. The third and final of Johnston’s assumptions, is the effectiveness of force. When considering a non-state actor such as Daesh, with no public policy papers and no diplomatic history, it is impossible to ascertain accurate results through the existing model of assumptions.

Fisher hypothesised that human beings are, as a species, homo narrans, (Fisher, 1984) a construction of our own design, brought to existence through the expression of narratives. This is particularly prudent for the analysis of non-state actors, especially those which are often physically diasporic such as terrorist organisations; because the national mythology that binds and motivates fighters is, in itself; a constructed narrative to provide a meaningful pattern to what would otherwise be a series of random and disconnected events (Riessman, 2008).

Consider for a moment, a hiker lost in the wilderness. To locate himself on the map, he must triangulate his position with bearings from known features. The thicker the line he marks on the chart, the less precise the end result is. If he is to precisely demarcate his position, he must use an appropriate tool. Narrative analysis is to Johnston’s assumptions, what a sharpener is to the hiker’s fine tipped pencil. The more precise the information fed in to the creation of each assumption, the more accurate the result.

Whilst the vigour with which the author condemns the actions of Daesh is not to be understated, to condemn and dismiss Daesh as evil and therefore irrational, puts the organisation beyond the realms of understanding (Nathanson, 2012) and so is not helpful for strategists, policy makers or academics. To refer back to the immortalised words of Sun Tzu, “…he who knows both sides has nothing to fear in a hundred fights” (Bowden edition, Calthrop Translation of Sun Tzu, 2010) J’amat al Tawhid wal Jihād has reared it’s ugly head under many names since its conception in 1993 (Burke, 2015), most recently as Daesh. It is long since time for us as academics to know them well.

CHAPTER II – THEORETICAL CHAPTER

To better understand non-state actors, we need a new model. I hypothesise that by blending strategic culture analysis as put forward by Johnston (1995), with approaches from narrative analysis, an academic is able to conduct what I call, strategic identity analysis. Strategic identity analysis is a new mode of analysis specifically tailored for use with non-state actors. In this chapter I first outline the pros and cons of strategic culture analysis. I then do the same for narrative analysis before explaining which attributes I take forward in to my new model of strategic identity analysis.

Strategic Culture Analysis Background

The disciplinary pedigree of Strategic Culture Analysis is firmly rooted in International Relations during the Cold War. First developed by Snyder during the 70s as a parsimonious model to plot the strategic culture of a state to explain or predict their actions. The discipline was designed to aid US policy makers, particularly the US Air Force, in anticipating their Soviet counter parts; (Snyder, 1977) but the impetus behind such thinking is far more ancient. Classical strategic authors Sun Tzu and also Machiavelli in their respective books, both entitled “the Art of War”, famously wrote of the value in understanding one’s foe (Bowden ed, Calthrop Translation of Sun Tzu, 2010) (Machiavelli, Campana, 2012). The idea was elegantly simple, distil an entire nation’s history and beliefs in to a short document. Elegantly simple, but imprecise. These models generally relied on the use of three questions or assumptions to triangulate a policy position which could then be plotted on to a strategic culture diagram. Johnston, (Johnston, 1995) would go on to develop this approach, codifying a framework which I update for the twenty first century and use as a foundational work in my strategic identity analysis model. His three assumptions approach relied on answering the following:

1: The frequency of war in human affairs

2: The nature of the adversary

3: The effectiveness of force

Johnston hypothesised that in answering these assumptions for an actor, its strategic culture would be revealed (Johnston, 1995). This approach has its merits. Strategic culture analysis was, in many ways, ahead of its time. It had an appreciation for the heterogenous international system. Recognising that rational actor models assumed a universal rationality (Beach, 2012) which isn’t necessarily reflected in reality. What may seem like an entirely irrational approach from one state perspective may in fact be entirely rational for another state. When Snyder first coined the term strategic culture analysis (Snyder, 1977), he hypothesised that this difference was due to variances between national and historic cultural factors between states. According to Snyder, (Snyder, 1977), people in the USSR were ‘socialized’ in to a strategic culture and the strategic culture of the USSR was too different to the USA for existing rational strategy models to apply.

Following the end of the Cold War, and the failure of existing models to predict the demise of the USSR, Strategic Culture Analysis fell out of favour. Indeed, were it not for the events of September 11th, 2001, Strategic Culture Analysis may have remained little more than a footnote on the disciplinary history of Security Studies. This is because the optimistic political discourse, ‘New World Order’ era and Fukuyama’s ‘The End of History’ (1989) were pervasive ideas and suggested that liberal democracy was now a universal truth; as such, there was no need to develop models for understanding actors who were diametrically opposed to Western liberalism. The post 9/11 era saw a renaissance as strategic culture analysis became seen as a method to explain the actions of an organisation apparently so vastly different from the US and with no public policy papers to analyse (Defense Threat Reduction Agency Advanced Systems and Concepts Office, 2006).

The three assumptions by Johnston (Johnston, 1995) established a model for analysis which was asking the right questions. The approach frames strategic culture as something which can be understood and in doing so, it affords policy makers a greater insight in to the rationale of actors who otherwise may appear incomprehensible. Strategic culture analysis recognises that actors are not homogenous. The definition of a rational response to a strategic policy problem is subjective. What seems appropriate and proportional for the one actor may not seem appropriate and proportional to another and vice versa.

Strategic culture analysis is not without its short comings though. By Snyder’s (1977) own admission, culture and identity are fluid concepts which change but strategic culture analysis is a positivist approach which strives for the empiricism found in the natural sciences. Snyder argued that this wasn’t problematic because he believed cultural practices would take many years to change and so the literature would be able to keep up with these developments. However, the construction of a narrative is a constant process (Bruner, 1991) and the overall narrative becomes an entity in and of itself, inseparable from identity (Fisher, 1985).

Furthermore, because strategic culture analysis, at its epistemological roots, is a model designed for analysing states, it doesn’t necessarily apply to non-state actors. Because non-state actors lack a bureaucracy and the capacity to engage in international relations, the majority of data is qualitative and often comes from propaganda, and reports rather than from policy papers, observable norms and official documents.

If conducted as a desk-based study, strategic culture analysis is based on assumption. Strategic culture analysis, through its existence, recognises the fact that the West-centric consciousness is not the only one present in the international order, however, it fails to step outside of the traditional western nodes of analysis. The actor being analysed is still viewed from the outside in rather than from the inside out.

Finally, it is important to note that non-state actors cannot act in the same way as state actors, so they should not be analysed in the same way. The effectiveness of force is one assumption which simply does not apply well to non-state actors. This is because conventional force is not an option for non-state actors and so, if the traditional understanding was applied, non-state actors would never engage in conflict with states, especially a superpower like the USA, because it would be impossible to achieve victory. Yet we see that non-state actors such as Daesh do engage in asymmetric operations against powerful states. This is often written off in mainstream media and in political discourse as ideological zeal or insanity. Such sweeping generalisations are not helpful in understanding an actor. This phenomenon must be explained. We return to these concepts later.

Narrative Analysis

The post structural methodology of using narrative analysis to develop an understanding of identity, whilst new to the field of strategic culture analysis, has been proven time and time again by feminist IR security scholars. According to Polkinghorne (1981) narratives are central in the creation of personal identities. Ochs and Capps (1996) go further; defining narratives as storied understandings of life that have a formative role in the creation and maintenance of identities. The construction of identities is of particular interest for scholars and strategists investigating non-state actors, particularly those like Daesh who collectivise, recruit and fight along cultural or religious lines.

Narrative analysis is not without its shortcomings however. The potential for mistranslation or misinterpretation of language is great. A further critique of narrative analysis is that it lacks a clearly defined model through which actors can be analysed. Instead, narrative analysis take a less empiricist approach. Nordstrom, (Nordstrom, 1998) for example, explores the stories and narratives told by survivors of the Mozambique civil war to explore the rationalities and identities constructed. Whilst this suits the qualitative nature of the data and allows for broad stroke understandings of identities, it lacks a rigorous methodology which can be transplanted from one case study to the next. Simply exploring stories to understand a war or conflict is difficult to repeat and replicate in the absence of a clear structure of questions to explore. This means that the efficacy of narrative analysis as a tool for use by strategists may be limited because the reading of these narratives is often open ended and so results are not necessarily repeatable. This is because of the subjectivity of narratives. If positivist social scientific observations are fallible because the person conducting the study necessarily impacts on the observations, this can be equally true of narrative methods. As Reissman (2008) pointed out, narrative is constructed with an audience. Whilst Nordstrom’s methods work well for her field-based study. In conducting a desk-based analysis of narrative, the academic to some degree becomes the audience (albeit an unintentional audience). Because of this, it becomes very difficult to distinguish the narrative constructed with the intended audience, and the one which the academic constructs themselves. Just as the natural scientist must establish standardised lab conditions for inquiry, so too must the social scientist codify a framework through which strategic actors may be analysed.

The advantage of strategic identity analysis is in the codification of an approach. The methodology is clearly outlined with a series of questions which must be answered using the narratives put forward by the organisation themselves. These questions are broad, and neutral of any value judgements; so they can be applied to different groups or different narratives from the same group to demonstrate repeatable results.

Indeed, this problem is exacerbated when multimodal narratives are analysed. Ochs and Capps stated that narratives are “not usually monomodal” (Ochs, Capps, 1996 p20) and often comprise of other means of communication such as facial expressions or pictures. Daesh uses photographs in Dabiq, but owing to the equivocal nature of pictures and subjectivity of interpretation, I think the model for conducting a multimodal narrative analysis would be complicated and difficult to apply to other case studies. For this reason, narrative analysis is best thought of as providing the methodological framework and lens through which other models might be applied to a case.

The Blended Approach: Strategic Identity Analysis

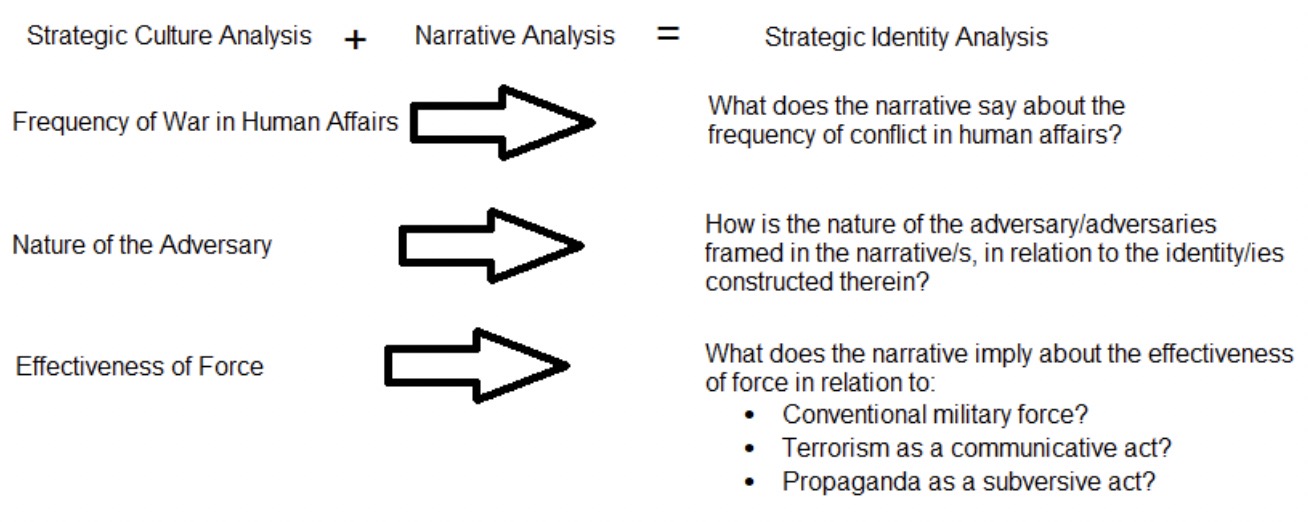

(Fig 1) disciplinary roots of strategic identity analysis

As we have seen, strategic culture analysis is generally asking the right questions, but not necessarily framing them in the right way to analyse non-state actors. Through considered use of narrative analysis, an academic can understand an identity constructed by a non-state actor and so conduct an analysis which is inside out rather than outside in. This blended approach results in a strategic identity analysis.

As demonstrated, strategic culture analysis is a model tailored for states as the unitnof analysis. As a result, some of the terminology is inappropriate or inapplicable to non-state actors and so the three assumptions have been slightly reconceptualised to allow for a more nuanced reading of strategic actors be they state or non-state. This reconceptualization is shown above in Fig 1. The term ‘war’ is a loaded one because of the monopoly of violence held by the state in western discourse. So it was replaced with the term ‘conflict’ to avoid analysis being diverted from the actor’s strategic identity towards questions of legitimacy and morality because from a traditional Hobbesian perspective, only the sovereign state has a legitimate right to force and the monopoly on violence (Hobbes, 2005). The ‘nature of the adversary assumption’ has been focussed more narrowly and framed as a question for ease of use when conducting a strategic identity analysis. Finally, the effectiveness of force and this conceptualisation of force in traditional conventional terms is not beneficial for the understanding of non-state actors. For my strategic identity analysis model, I reconceptualise force for the twenty first century to better suit analysis of non-state actors. I hypothesise that force for non-state actors such as Daesh comprises of three different methods: conventional military force, terror as a communicative act (Paldan, 1983), and finally propaganda as a means of subversion. Through this reconceptualisation of one of Johnston’s assumptions, I hypothesise that we are better equipped to understand why a non-state actor might deem it appropriate to engage in a subversive propaganda war rather than an asymmetric conventional conflict which it could not win. Likewise, by considering the use of terror as a communicative act, the efficacy of seemingly irrational, costly and tactically unsound attacks such as suicide bombings can be explained as part of a wider strategic approach to conflict.

Strategic Identity Analysis Methodology

The strategic identity analysis model that I propose, uses a three-step approach similar to the strategic culture model put forward by Johnston (1995) but seeks to answer each of those questions through a thorough reading of the literature and narratives produced by the actor to try and ascertain a better insight in to the identity/ies constructed by the actor themselves. Snyder (1977) hypothesised that national heritage and historical experiences shape strategic policy, I build on his work and go further, using the works of narrative analysis theorists who said that meta narratives can be self-produced (Bruner, 1990) and a construction in and of themselves (Reissman, 2008) and a construction of the plot (Polkinghorne, 1981) which in turn provides a frame of reference for identity and the construction of future narratives in relation to events (Bruner, 1991). These academic works, establish a disciplinary precedent for the notion that identity can be constructed through narrative and therefore, it can be interpreted and analysed through a close reading of the narratives. This theoretical thought process, when applied to the context of strategic actors, provides the necessary methodological framework for strategic identity analysis.

Because Daesh produces media in a variety of languages to reach different audiences, narrative analysis could be conducted across a wide range of material. For the purposes of this paper, only material produced in English will be analysed. This is to avoid the potential for mistranslation adversely affecting the accuracy of the model. In the construction of the case study below, I refer primarily to Dabiq, the magazine produced for the anglophone world.

I hypothesise then that the methodology for conducting a strategic identity analysis is as follows;

Material produced by the non-state actor being analysed must be identified and selected. The intended audience for this material must then be identified. This is because narratives are not constructed in isolation, they are produced interactively with both an audience and a context (Reissman, 1998). Once the material is selected and both the context and intended audience are identified, the analysis can begin.

As already mentioned, the three-step model I propose is based on that put forward by Johnston for strategic culture analysis and requires the following questions to be answered:

- What does the narrative say about the frequency of conflict in human affairs?

- How is the nature of the adversary/adversaries framed in the narrative/s, in relation to the identity/ies constructed therein?

- What does the narrative imply about the effectiveness of force in relation to:

- Conventional military force?

- Terrorism as a communicative act?

- Propaganda as a subversive act?

In answering these three questions using the narratives constructed by the non-state actor themselves, I hypothesise that a strategic identity of the actor can be revealed. It is important to note however, that identities remain fluid and so they are subject to change as the narratives and contexts which construct them change. This is not to say that the model is flawed, rather, the caveat provides scope for constant re-evaluation of the actor. Furthermore, as an actor can exhibit multiple identities, so to may they exhibit multiple strategic identities. Perhaps constructed within a singular narrative, but more than likely, constructed with a series of overarching meta-narratives (Streib, 1997) which may or may not be conflicting (Nordstrom, 1998). This is especially true of groups like Daesh which are comprised of many different languages, nationalities and ethnicities. As such, strategists should seek to engage in multiple readings of as many narratives as possible to conduct the most thorough strategic identity analysis. For the purposes of establishing a strategic identity model in this paper, only the narratives put forward in Dabiq issues 8-10 will be analysed.

CHAPTER III – CASE STUDY

As already mentioned, I will apply my model for strategic identity analysis to Daesh. Because this is an initial work supporting my hypothesis, in the case study I’ll be limited to exploring only the strategic identity constructed in material Daesh has produced in English for the Anglophone world. Though I make no claim that the strategic identity revealed through my analysis is the only strategic identity held by the group, nor is it to say that it is a static position which Daesh will continue to hold. Indeed, the fact that Daesh is able to produce such a wide range of media in so many different languages would indicate that there may be any number of strategic identities constructed within the organization and its multiple different audiences (Reissman, 1998).

Before this chapter begins in earnest I detail the overarching narratives from each issue of Dabiq from 8–10. These narratives continue to be developed throughout Dabiq issues 10-15, but for the purposes of brevity in establishing the methodological foundations for strategic identity analysis, only issues 8, 9 and 10 are analysed and discussed. In doing so, I produce a road map of meta narratives which allows a deeper contextual reading of each of the three questions in my strategic identity model whilst keeping this paper necessarily brief. After the narratives are listed, the model is applied to the case study. I start by considering the frequency of conflict in human affairs. Finding that conflict is framed as a prerequisite of existence for Daesh which fits within the Huntington (2002) understanding of jihādists. However, this is contrasted with the heavy focus on fulfilling the requirements and functions of legitimate statehood, present throughout the literature. It seems then, that the narrative put forward regarding unending conflict may be a rhetorical or recruiting device rather than representative of the aims of the organisation.

I then go on to consider what Daesh writes about the nature of the adversary. For Daesh, there are multiple adversaries to consider. Quite aside from the popular misconception put forward by Huntington (2002) that there is some sort of clash of civilisations between the Islamic world and the West, this paper breaks down Daesh’s adversaries to include co-religionist apostates, and regional powers as well as the Western world.

The third point of analysis is the effectiveness of force which, I have reconceptualized to encompass military force, terror as a communicative act and finally propaganda as a means of force. Finally, I conclude this short strategic identity analysis by summarising my findings; that Daesh, through the literature analysed, constructs a narrative of traditional Montevideano statehood (Montevideo Convention, 1933–1936). There is a dichotomy between the narratives constructed by Daesh. On the one hand, it opposes nationalism and on the other, it tries to appeal to it and fulfil functions of statehood. These diametrically opposed narratives provide us an insight in to the strategic objective of Daesh, which I suggest is sat somewhere in between the two positions, establishing a theocratic state.

How Does/Do the Identity/Identities in the Literature Express Perceptions of the Frequency of Conflict in Human Affairs?

In Dabiq, Daesh constructs its strategic identity in relation to conflict with the ‘other’. Much of the text across issues 8-10 of the magazine is devoted to defining the enemy and discussing the obligations placed on followers of the organisation to wage jihād. This at face value would indicate that Daesh has constructed a narrative of constant, inevitable conflict. The groups original name when founded in 1999 (Jama’at al-Tawhid wal-Jihād) literally translates to mean ‘Organisation of Monotheism and Jihād’. At the heart of the Daesh’ values, it considers that any deviation from its own extreme brand of Jihādist Wahhabi Salafism to be haram, forbidden (Burke, 2015).

Daesh believes that as it has declared a Caliphate, it is required to wage offensive jihād at least once a year to further the territories of the caliphate. This attitude is echoed repeatedly throughout different issues of Dabiq. In this section I explore the way in which the perception of conflict is framed by Daesh and how that relates to the identity they are constructing within the narrative. I do this first by analysing the dichotomy presented by Daesh’s argument against statehood and factionalism whilst pursuing a defined territory of their own. I then discuss the way that ideas of conflict are conflated with the divine in regard to the payment of Zakah, the tax or tithe owed to Daesh. Finally, I consider the way that Daesh presents itself in relation to its enemies, who, the organisation claims, have been put on the Earth solely for the purpose of being destroyed by the believers, before concluding this section with a quote from the editor of Dabiq which summarises the section succinctly.

The reason that the term war had to be removed from my strategic identity model and replaced with the term conflict, is because Daesh engages in conflict without satisfying many of the criteria of warfare. For example, on page 22 of Dabiq issue 8 (Dabiq 8, 2015), Daesh discusses “Erasing the legacy of a ruined nation”. This concept of fighting the history and identity of Iraq by destroying ancient artefacts ties neatly to Dabiq issue 9 in which Shaykh Abū Mus’ab az-Zarqāwī is quoted as saying, “We do not perform jihād here for a fistful of dirt or an illusory border drawn up by Sykes and Picot. Similarly, we do not perform jihād for a Western tāghūt to take the place of an Arab tāghūt. Rather our jihād is loftier and more superior…{And fight them until there is no fitnah and [until] the religion, all of it, is for Allah} [Al-Anfāl: 39]” (Dabiq 9, 2015).

The identity put forward across these two issues is one of staunch opposition to the colonial world. Tribal, national and ethnic allegiance is framed as abayillah (factionalism) and described as ‘shirk’. Daesh is presenting itself in these two issues as the antithesis of the perceived evils of factionalism, instead, the identity constructed here is one of Islamic asabiyya, (social unity and cohesion through shared purpose) of an egalitarian society based on universal moral truths. This method of constructing identity in relation to an enemy is further explored in point [III.2] entitled: ‘How does/do the Identity/Identities Constructed in the Literature Relate to the Nature of the Adversary?’.

This clearly defines the nature of the conflict Daesh sees itself embroiled in. In Dabiq 8, Daesh puts forward a narrative of a conflict which can only end with victory. Victory for Daesh is defined here as the absence of fitnah, the end of the trials and struggles which they believe have plagued the Ummah since creation. Daesh constructs a narrative across Dabiq 8 as the victim of systematic abuse by colonial powers. It is interesting then that the words used to describe victory conditions are related to the ending of struggle rather than the eradication of the enemy as would be suggested by Huntington (2002).

Daesh goes further to tie jihād with the functions of statehood. Linking jihād with raising taxes or zakah. “…as soon as I saw that Allah opened Abu Bakr’s heart (radiyallahu ‘anh) towards war, I knew it to be the truth’” (Dabiq Issue 8, p13, 2015) – Abu Bakr is afforded a position of moral superiority because of his perceived closeness to Allah. This is used to justify the waging of jihād on those who fail to pay zakah. By conflating the actions of Abu Bakr As-Siddiq with divinity, he, and by extension, Daesh, become beyond reproach. Conflict is framed in this way as a religious obligation to the Khalifah and by extension to the divine. All this whilst also demonstrating that in this narrative, the duty to jihād was predicated upon the existence of the state (Dabiq 8, 2015).

Dabiq issue 9 page 3 (Dabiq 9, 2015) describes the actions of the two jihādists who attacked the Curtis Culwell Center in Garland, Texas and says that the attack should serve as an inspiration for others living in the lands of Kuffar to fulfill their obligation to jihād. This is in reference to the doctrine of defensive jihād first put forward by Sheikh Abdullah Azzam (Burke, 2015). From this information then, we as academics and strategists can infer that Daesh accepts the tenets of Azzam put forward (Azzam, 1979) and this then provides an additional source of reference material to provide context for any assertions made through strategic identity analysis.

In an articulate piece featured in Dabiq issue 10 (2015), the author details the religious obligation of all believers to obey and love their parents. However, the real message hidden within this seemingly innocuous text comes later. Jihād is framed in Dabiq issue 10, page 15 (Dabiq 10, 2015) in a quote from Ibn Qudāmah, as an obligation which takes precedence over the will of the believer’s parents. This article appears to be targeted at recruiting for ashbal or lion cubs for Daesh’s army. This article is explored further in regard to its efficacy as a propaganda tool in point III.3.C entitled: Propaganda as a Means of Force.

For now though, in relation to the perceived frequency of war in human affairs, jihād is described as Fard’ ayn – a holy obligation above all others (Dabiq 10, 2015). It is framed alongside the less controversial obligation on all believers to pray. This association of moderate, widely accepted religious practice with extreme violence serves to construct an identity of pious militarism. The military strength and religious piety of Daesh are presented as indistinguishable from each other.

Issue 8 of Dabiq (2015) frequently refers to the perils of hypocricy. On page 51, it is explained that Allah does not choose to eradicate the hypocrites Himself because in doing so, He would deny the Ummah the opportunity to “exact revenge on your [sic] enemies”. This suggests that the co-religionist apostate enemies of Daesh exist for the purpose of being a target for the violence of the organization. Here Daesh constructs a narrative of being tested by the divine – by allowing the apostate hypocrites to exist, Allah affords Daesh an opportunity to not only exact revenge, but also an opportunity to demonstrate their piety and religious devotion. Creating their devotion in the mirror of hypocrisy just as Daesh constructs their identity in terms of the ‘other’.

In summary, across Dabiq issues 8-10, Daesh constructs a number of identities. The overarching meta narrative across the three issues of the publication, with relation to the frequency of conflict in human affairs, is one of absolute certainty. Conflict for Daesh is not an abhorrent anomaly, rather, conflict is at the heart of the group’s reason to exist. The fabric of the organization is entirely dependent upon the existence of enemies and the obligation to fight them. That said, the importance of performing state functions are levelled with the duty to jihād and presented as justification for conflict, blurring the boundaries between the two concepts.

I close this section with a quote from Dabiq issue 8 page 67 (Dabiq 8, 2015);

Editor’s note: A halt of war between the Muslims and the kuffar can never be permanent, as war against kuffar is the default obligation upon the Muslims only to be temporarily halted by truce for a greater shar’I interest…

How does/do the Identity/Identities of the Organization, Constructed in the Literature Relate to the Nature of The Adversary/Adversaries?

In conventional wisdom, the conflict between Daesh and the rest of the world is zero-sum. Daesh identifies everyone with a different belief system to theirs as a heretical enemy, kafir, infidels. The idea of negotiating with them is simply out of the question. This was exemplified by the many attacks on Shiite Muslims orchestrated by Daesh (then AQI) in Iraq during the second gulf war. These attacks drew condemnation from across the international Muslim community including the most extreme Salafist groups and eventually led to their formal separation from Al Qa’idah, to whom they had sworn allegiance in 2004 following the US led invasion of Iraq. In this section, I explore Dabiq issues 8-10 to find the identity/identities constructed within their pages in relation to the nature of their adversary/adversaries. Broadly speaking, Daesh has three enemies, the near enemy, comprised first of Arab states or Taghut, secondly as apostates, including co-religionist apostates such as Shia Muslims as well as atheists, Christians and Jews. Finally, there is the far enemy, broadly defined as the West or the “Army of Rome” (Burke, 2015). First I analyse the strategic identity constructed in relation to the near enemy, then the apostates before finally focusing on the far enemy. Though it is important to note that these enemies are not mutually exclusive, many of the adversaries are presented in Dabiq as comprising a wider coalition of unbelievers fighting against Daesh. The subsections then are more of an approximate guide for ease of analysis and reading rather than clear cut comprehensive divisions. Each of the adversaries is then brought together in a conclusion which highlights the way in which, even when discussing enemies, the identity established by Daesh in the literature analysed, is one of egalitarian unity. Daesh continues to construct an identity of a kind of Islamic utopia in which race, tribe and nationality are all irrelevant. In this way, I argue that Daesh is on one level, using the language of an international counter culture similar to that suggested by Huntington (2002), whilst actually pursuing the most internationally conventional goal of all, statehood and legitimate recognition.

Everyone who opposes…is an enemy for us and a target for our swords, whatever his name may be and whatever his lineage may be…the American Muslim is our beloved brother. And the kāfir Arab is our despised enemy even if we and he were to have shared the same womb” – Shaykh Abū Mus’ab az-Zarqāwī (Dabiq Issue 8, 2015) “

The Near Enemy

In Dabiq issue 9 (Dabiq 9, 2015), the near enemy or Arab tawāghīt is explained in great detail. The context is an article about the history of Sham (Syria) and explains how the Arab tawāghīt was placed in a position of power, and held there, by British Imperial designs. The implied role of Daesh is primarily as the educator of the Ummah, and secondarily as a holy force to fight back against the Western construct of the nation state and subsequent Arab tawāghīts. When Analysing this article, it is vitally important that we not forget who the intended audience is (Reissman, 1998). A narrative is not constructed independently of its audience, but rather, it is constructed interactively with them. The intended audience for this issue of Dabiq is the Anglophone world. Dabiq is written to influence disenfranchised Muslims living in the West (Atwan, 2015). Education on Britain’s colonial past is notably absent from school curricula and so Daesh is able to construct the narrative with minimal risk of it being rejected. The shameful acts of the British Empire, combined with disillusionment, allow Daesh to present Arab national projects simply as puppets of the Western ‘crusaders’ (Dabiq Issue 9 Pages 24–28, 2015)

Apostates

Dabiq issue 8 focuses primarily on co-religionist adversaries. Through consistent denigration of rival jihādist groups in Sham (Syria), Daesh establishes an identity of theological superiority and asserts itself as possessing the monopoly on the application of legitimate force in the same way that States do in the West (Dabiq Issue 8, page 39–56, 2015). On Page 19 (Dabiq issue 8 page 19), Daesh addresses criticism it has received from Al Qa’idah in the wake of the Daesh orchestrated bombing of a Houthi temple in Yemen. Al Qa’idah’s criticism on the grounds of Dhawahiri’s guidelines is dismissed as “blind partisanship”. The rivalry between Al Qa’idah and Daesh is a constant feature in the identity of the organization since the split in 2008. Both organisations claim legitimate religious and militant authority over the Ummah and so they are in the bizarre position of being ideologically very close whilst politically, diametrically opposed. Daesh carefully frames Al Qa’idah as hypocritical, citing a bombing of a Houthi rally in a public square as evidence of Al Qa’idah’s perceived double standard. This is particularly significant because the over-arching narrative of Dabiq issue 8 is about the hypocrisy of co-religionist apostates. By pointing out a double standard in Al Qa’idah’s position, Daesh implies apostasy without making an accusation and subsequently Daesh is able to avoid the risk of Takfir – falsely accusing a believer of apostasy, which in itself would be shirk – a forbidden religious practice which would compromise the morality of the accuser.

This careful choice of words demonstrates a high level of cultural competency. Dabiq Issue 9 (2015) goes further. In an article entitled: The Allies of al-Qā’idah in Shām: Part II, Daesh presents their jihādist rivals as being associated with a number of organisations who “are puppets of the Arab tawāghīt”. This association between jihādist groups that oppose Daesh, and the Arab states who oppose Daesh delegitimises the other jihādists and further serves to construct this identity of Daesh being the only legitimate jihādist force and therefore the only organization with a legitimate right to exact violence.

In Dabiq issue 8 page 16 (2015) the enemy faced in West Africa by Daesh’s offshoot Boko Haram is listed as a mixed force comprising “the murtad forces of Chad and Niger…in addition to the troops recently deployed from the Cameroon, as well as mercenaries, and even the French ‘crusaders’ based in Chad…”. This framing of the adversary as a multinational force being supported by European ‘crusaders’ allows Daesh to assume the role of an underdog thus making any victories against such a large coalition seem more impressive. Indeed, the next page of the magazine is an article all about victories won by ‘soldiers of terror’.

The Far Enemy

Daesh is a framed as a cleansing influence on the region. On page 22 of Dabiq issue 8 (2015), statues and historical artefacts in Iraq are presented as a kuffar plot to unify the Muslims of Iraq under nationalist boundaries. The article goes on to describe how mujahidin destroyed the artefacts to defeat this nationalist agenda. This, coupled with the foreword in the same issue (Dabiq Issue 8 page 3) constructs an image of Daesh as an egalitarian force with no interest in class, race, ethnicity, tribe or national citizenship. Indeed, all of these divisions are presented as a construct of the far enemy to divide, subvert and control the Ummah.

The adversary is framed consistently as an organised force all serving the same cause. The framing of Arab leaders as Tawaghut puppets and the presentation of other jihādist groups as hypocritical apostates who work for western crusaders belies the complexity of the situation on the ground and constructs a narrative of binary morality. The conflation of the various adversaries Daesh is opposing in to a morally corrupt or ‘shirk’ force affords Daesh a position of unquestionable moral superiority despite the various atrocities committed by the organisation. The overriding meta narrative on this subject, woven through the literature analysed, is one of Islamic utopia. The enemy is unified in apostasy and heresy, and so in the same way Daesh is presented as being unified in devout religious practice and moral practice.

How does/do the identity/identities constructed in the literature present the effectiveness of force with regard to; traditional military force and violence, the use of terror as a communicative act and the use of Propaganda as a means of force?

When analysing the effectiveness of force, I have divided force in to three categories. The first is traditional military force and violence, the second is the use of terror as a communicative act – primarily, but not exclusively against the far enemy. The third, and most effective means of force that Daesh utilizes, is the exertion of soft power through the production and distribution of high quality propaganda material. It is through propaganda that Daesh was able to attract 20,000 (Neumann, 2015) fighters to leave the relative comforts of their homes to participate in hijrah (a pilgrimage to the lands of the Caliphate) and live under the black flags of the Caliphate.

Military Force and Violence

Daesh, through offensive jihād, seeks to extend the borders of the caliphate to eventually encompass Rome and Constantinople. Initial military campaigns in the Middle East such as the breaking of the walls campaign in Iraq, were very successful and led to vast swathes of territory being very quickly claimed by the organization. Dabiq talks about growing the Khilafah’s control, citing the expansion in Nigeria (Dabiq Issue 8, 2015) as well as the capture of a military base in Iraq (Dabiq Issue 9, 2015) as evidence of conventional military success in carving out a territory.

Furthermore, Daesh chooses the word state one hundred and forty five times in Dabiq issue 8 (2015) whilst using the word caliphate only nine times in the same issue. The primary focus of the organisation then, appears to be conventional statehood. Whilst decrying nationalism as a Western construct which is anti-Islamic, Daesh uses the language of nationalism to promote their ideas about an egalitarian, Islamic utopia. As a result, conventional military force and recruitment are very important to the organisation because it is through these means that Daesh might expand its borders to occupy more territory.

Terror as a communicative act (Paldan, 1983)

Daesh uses terror as a communicative act (Paldan, 1983). The mujahidin campaigns across Nigeria are described as “a tremendous cause of celebration for the Muslims and yet another source of gloom for the kuffar (Dabiq issue 8 page 14).

Perhaps the clearest example of the use of terror as a communicative act is seen in Dabiq issue 8 Page 17 (2015); “This month, the soldiers of the Khilāfah sent a forceful message to the camp of kufr…striking and terrorizing them… and with no visas, borders, and passports to stand in the way. Strikes were carried out…by men whose allegiance lies, not with a false citizenship, but with Allah, His Messenger, and the believers. They readily sacrificed themselves…bringing massacre to the disbelievers and murtaddīn, not differentiating between them on grounds of nationalism.” (Dabiq Issue 8, Page 17). This quote exemplifies the use of terror as a communicative act and constructs Daesh as a far-reaching organisation who operates on a higher plane than that of the nation state. The concept of nationalism is yet again decried here, and the narrative is one of divine justice striking at the core of the international order, the nation state. The article goes on to describe, on page 18 (Dabiq, Issue 8, Page 18, 2015) an attack as an operation that “succeeded in bringing anguish to…[the] crusader coalition…” this state the intended aim of the attack to be inflicting anguish on the far enemy.

Soft power and propaganda as a means of force

Daesh demonstrates a level of cultural sensitivity and awareness in its literature. The organization clearly makes an effort to produce material for specific audiences, recognizing the cultural and linguistic nuances that exist among different audiences and then exploiting those to great effect. The material is produced in a targeted manner to reach specific audiences. As already mentioned, this case study deals exclusively with English material produced for the anglophone world, particularly the magazine Dabiq. Dabiq is a glossy magazine put together with high production values. Each issue of the magazine is approximately 60–70 pages in length and features high resolution images alongside opinion pieces and interviews with theologians and jihādists. The magazine also features quotes from Western policy makers and strategists, generally painting Daesh as a formidable foe and a force to be reckoned with. This effective propaganda machine is credited with recruiting some 20,000 foreign fighters (Neumann, 2015) to join the ranks of the Khalifa and allows Daesh to grow its borders without using conventional military force. Propaganda and subversion as a means of force underpins the effectiveness of everything Daesh does. Without propaganda the organisation would be unable to recruit western attackers and suicide bombers (Burke, 2015). So propaganda can be seen as the primary tool which allows for the use of terror as a communicative act. Furthermore, whilst Daesh is reportedly exploiting local tribal conflicts in the region to expand its forces and eradicate opponents, the narrative established in Dabiq is one of anti-tribalism and anti-nationalism. Daesh is able to expand its borders in the minds of its followers rather than simply along geographical constraints. As referenced earlier (Moubayed, 2015), Tsagarianou (2004) states that nations are dependent on people sharing identity, rather than geography. Daesh exploits this concept, growing the Caliphate by collecting bay’ah (pledges of allegiance) from around the world.

Daesh accuses others of apostasy despite this, in itself, being forbidden as takfir. Whilst they weren’t explicit in this accusation about Al Qa’idah, it is explicitly said in regard to others. The risk of accusing someone of apostasy, is that only Allah can truly know, and if an accusation is false, the accuser has himself denounced the faith. This is used to great effect against the co-religionist enemies and the near enemy. By linking Islamic rivals to the far enemy, Daesh establishes a narrative which places themselves as stalwarts of the true faith. A bulwark in the crashing ocean of non-believers, Daesh becomes the only legitimate authority on the use of jihād and therefore all force used against them is shirk and the entire Ummah is obliged to support their cause.

Daesh, through overarching narratives in Dabiq, ‘othering’ abayillah factionalism and establishing their own brand of Islam as the true faith through theological arguments against opposing co-religionist rivals, constructs an identity of social cohesion and equality. The concept of an egalitarian state is constructed as intrinsically Islamic whilst commiting takfir to provide the ‘other’.

This focus on effective statehood is exemplified by an article in Dabiq entitled ‘Healthcare in the Khilafah’ (Dabiq 9, 2015) in which the author talks about the medical feats achieved by the healthcare professionals of the Khilafah. Indeed, they claim to have opened their own Medical College in ar-Raqqah and the College for Medical Studies in Mosul to enable them to prepare future generations of healthcare professionals. All this is done not only to recruit healthcare professionals, to whom this article is clearly targeted, but also to attract fighters to the region, safe in the knowledge that they will be joining an organisation with effective and virtuous state apparatus. This article, rather than simply serving as a tool for subversion or recruitment, is also intended to shape the discourse in the West. A regular feature in Dabiq is entitled ‘In the words of the enemy’ and includes quotes from Western policy makers talking about the severity of the threat posed by Daesh and suggesting the group is now a de-facto nation state (Dabiq 8, 2015). Using the words of the enemy to present themselves as internationally recognized, even if despised, provides Daesh with a sense of legitimacy required by all states to govern and echoes of the requirement for sovereignty – that the state be recognized internally and externally. The Anglophone audience to whom this publication is targeted, are used to exacting standards of healthcare and the concept of Westphalian sovereignty.

So, what is the strategic identity of Daesh?

Daesh constructs a narrative of unending conflict whilst simultaneously constructing a narrative of legitimate statehood. These two strategic objectives are at odds with each other. Either Daesh wants endless conflict, or, they want to secure a territory and govern it. By presenting both narratives, Daesh is able to construct more than one identity and so appeal to a greater number of possible followers who may identify with one strategic identity more than the other.

I then analysed the way in which the identities constructed in the literature related to the nature of the adversary. The difference between Daesh and western or even Arab states is a focal point of the literature. Much time is spent on framing rival jihādist groups and rival states as colonial projects and therefore present them as one and the same. The adversaries are conflated in to one homogenous force of immorality and this affords Daesh a unique position of moral superiority. Furthermore, the organisation eludes to racism in western states and so tries to appeal to the disenfranchised youth who have suffered discrimination. Claiming that there is no difference between Muslim members of the group based on national or ethnic identity constructs a compelling picture of egalitarian utopia for believers.

Finally, the effectiveness of force is framed in three distinct ways to further construct this strategic identity of legitimate religious statehood. The efficacy of conventional force serves to demonstrate that Daesh can defend and expand its borders – a key requirement of Westphalian statehood. The use of terror as a communicative act represents the organisations ability to strike its enemies around the world but also in a perverse sense, demonstrates the capacity or at least willingness to enter in to relations with other states. Those relations may be destructive in nature, but all the same, Daesh is sending messages through its attacks. Last but not least, the use of propaganda as a means of force is not so much a theme presented in the literature outright, but it is something which can be inferred through a close reading. Talk of recruitment and Bay’ah obviously speak of the draw of Daesh in building a permanent population, but the narratives around effective statehood, medical care and bureaucracy are the most significant found in Dabiq. These articles construct an identity of effective statehood and invite the reader to come and be a part of the state project. The strategic identity constructed in Dabiq issues 8–10 can be said then, to focus primarily on asserting the legitimacy of Daesh by constructing an image of an Islamic polity that fulfils the criteria of statehood.

From this strategic identity analysis we academics and strategists can infer that achieving these aims is the primary goal of the strategic identity represented in the literature. This may serve to inform policy makers on intelligent strategic options to counter the narratives being established by Daesh and in doing so, undermine the organisation at a political and identity level rather than simply engaging in asymmetric warfare in the tactical sphere.

CHAPTER IV – CONCLUSION

This paper has built on the work of later Strategic Culture theorists such as Johnston and Narrative Analysis theorists such as Bruner and Reissman to, using the context of Daesh as a case study, provide a model which is tailored for use when analysing the strategic identity of non-state militant groups. Strategic culture analysis is an outdated means of strategic analysis. Its inability to properly approach non-state actors as a unit of analysis means that modern asymmetric conflicts are rendered incomprehensible. Existing models of narrative analysis allow for a closer reading of non-state actors like Daesh but lack the methodological rigour to produce succinct meaningful results in an established framework which can be transplanted and applied to different case studies. Strategic identity analysis enables IR scholars to develop and explore new understandings of non-state actors like Daesh. The methodology takes the base framework for strategic culture analysis as put forward by Johnston (1995) and adjusts the terminology used for the 21st century.

Strategic identity analysis bridges the gap between the two approaches of strategic culture analysis narrative analysis, through reconceptualization of key terms used in Johnston’s framework to remove any implicit bias or normative statements towards states. Then, through careful and considered analysis of the literature of a non-state actor, narratives can be identified. These narratives, when applied to the strategic identity analysis model, afford the academic and strategist alike, a new insight in to the self-constructed strategic identity/identities of the strategic actor. The framework put forward in this paper is new and original, but fits neatly within conventional practices of strategic studies and IR. Indeed, the aim of this framework finds its roots in classical strategic authors such as Sun Tzu. Strategic identity analysis is simply a new framework for achieving the ancient strategic goal of understanding one’s enemy which has been updated for the historical context in which we find ourselves today.

The greatest difficulty I faced in producing the strategic identity model was in the case study. Because this is only a foundational work, I was limited in the level of detail that I could achieve. I was also limited solely to English material rather than being able to engage with material in other languages. Though I recognise the limitations in the quality of analysis that can be achieved through such a restricted reading, I believe the model shows promise and it is my intention to further apply it in future works, to conduct a more robust analysis of the strategic identity of Daesh.

References

Abbott, H.P. 2008, The Cambridge introduction to narrative, Second edn, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Al-Muntada Al-Islami, (2009). The Qur’an: English Meanings Revised & Edited by Saheeh International. Riyadh: Abul-Qasim Publishing House.

Atwan, AB. (2015) Islamic State the Digital Caliphate. Second Edition. London: Saqi Books.

Azzam, A. (1979) Defence of the Muslim Lands [online]. Not Given. (Year of publication) Title [online]. Edition (if not first edition). [Accessed 22 May 2018].

Beach, D. (2012) Analyzing Foreign Policy. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Berger, JM, Stern, J. (2015) ISIS The State of Terror. London: Williams Collins.

Browning, CS. (2013) International Security a Very Short Introduction. . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bruner, J. (1990) Acts of Meaning. Harvard: Harvard Universtiy Press.

Bruner, J. (1991) “The Narrative Construction of Reality”, Critical Inquiry, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 1-21.

Burke, J. (2015). The New Threat From Islamic Militancy. London: The Bodley Head.

Burnham, P, Lutz, KG, Grant, W, Layton-Henry, Z. (2008) Research Methods in Politics. Second Edition. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

R. A. Gribben 2006, “The Literary Cultures of the Scottish Reformation”, The Review of English Studies, vol. 57, no. 228, pp. 64-82.

Collins, A. (2016) Contemporary Security Studies. Fourth Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fisher, W.R. (1985) “Homo Narrans The Narrative Paradigm: In the Beginning”, Journal of Communication (pre-1986) [Online]. 35(4), pp. 74. [Accessed 12 October 2017]

Fukuyama, F. 1989, THE END OF HISTORY?: As Our Mad Century Closes, We Find the Universal State The End of History, WP Company LLC d/b/a The Washington Post, Washington, D.C.

Gibbon, E. (1910) The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire: Mohammed and the Arabs. Sixth Edition. Bath: The Folio Society Limited.

Gray, C.S. 1981, “National Style in Strategy: The American Example”, International Security, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 21-47.

Gray, C.S. 2013, “The strategic anthropologist”, International Affairs, vol. 89, no. 5, pp. 1285-1295.

Hehir, A. (2013) Humanitarian Intervention. Second Edition. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hobbes, T., Rogers, G.A.J., Schuhmann, K. 2005, Leviathan, .London: Continuum.

Huntington, S.P. 2002, The clash of civilizations and the remaking of world order, Free, London.

Irshaid, F, / BBC (2015) Isis, Isil, IS or Daesh? One group, many names. Available from: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-27994277 [Accessed 10 October 2018]

Jerry Mark Long Prepared for: Defense Threat Reduction Agency Advanced Systems and Concepts Office Comparative Strategic Cultures Curriculum Contract No: DTRA01-03-D-0017, Technical Instruction 18-06-02 STRATEGIC CULTURE, AL-QAIDA, AND WEAPONS OF MASS DESTRUCTION. Online. [Accessed 10 October 2017]

Johnston, A.I. (1995). “Thinking about Strategic Culture”, International Security, vol. 19, no. 4, pp. 32-64.

Lamont, C. (2015) Research Methods in International Relations. . London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Machiavelli, N. & Campana, J. 2012, The Art of War.

Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 1977. Available from: https://www.rand.org/pubs/reports/R2154.html. [Accessed 10 October 2018].

Montevideo Convention (Convention on Rights and Duties of States adopted by the Seventh

International Conference of American States) 1933-1936 (RN 3802)

Moubayed, S. (2015) Under The Black Flag. Second Edition. London: I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd.

Nathanson, S. (2012) Terrorism and the Ethics of War. Second Edition. Cambrdige: Cambridge University Press.

Neumann, PR. / ICSR (2015) Foreign fighter total in Syria/Iraq now exceeds 20,000; surpasses Afghanistan conflict in the 1980s. Available from: www.icsr.info/2015/01/foreign-fighter-total-syriairaq-now-exceeds-20000-surpasses-afghanistan-conflict-1980s/ [Accessed 07 October 2017]

No Author. (2015) Break the Cross. Dabiq Issue 15. 2015.

No Author. (2015) From The Battle of Al Ahzab to the War of Coalitions. Dabiq Issue 11. 2015.

No Author. (2015) Just Terror . Dabiq Issue 12. 2015.

No Author. (2015) Shari’ah Alone Will Rule Africa. Dabiq Issue 8. 2015.

No Author. (2015) The Laws of Allah or the Laws of Man. Dabiq Issue 10. 2015.

No Author. (2015) The Murtadd Brotherhood. Dabiq Issue 14. 2015.

No Author. (2015) The Rafidah from Ibn Saba’ to the Dajjal. Dabiq Issue 13. 2015.

No Author. (2015) They Plot and Allah Plots. Dabiq Issue 9. 2015.

Nordstrom, C. (1998) “Terror Warfare and the Medicine of Peace”, Medical Anthropology Quarterly, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 103-121.

Ochs, E. & Capps, L. (1996) “NARRATING THE SELF”, Annual Review of Anthropology, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 19-43. rev. 20 November 2006

Paldán, L. (1983) Violence as Communication. Insurgent Terrorism and the Western News Media. Current Research on Peace and Violence [online]. 6 (1), pp. 68-73. [Accessed 20 April 2018].

Riessman, C.K. (2008) Narrative methods for the human sciences, SAGE, London;Los Angeles, Calif;.

Rougier, B. (2015) The Sunni Tragedy in the Middle East. English Translated Edition. Woodstock: Princeton University Press.

Roy, O. (1992) The Failure of Political Islam. Third Edition. London: I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd.

Snyder, JL. (1977). The Soviet Strategic Culture: Implications for Limited Nuclear Operations. Santa

Streib, H. (1997) “Mass Media, Myths, and Meta-Stories: The Antiquity Of Narrative Identity”, British Journal of Religious Education, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 43-52.

Sun Tzu (1908 Calthrop Translation, Bowden Edition). (2010) The Art of War Ancient Classics Including the Translated The Sayings of Wu Tzu With an Introduction by Tom Butler Bowden. Twelfth edition. Chichester: Capstone Publishing.

Tsagarousianou, R. (2004). Rethinking the concept of diaspora: mobility, connectivity and communication in a globalised world. Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture [online]. 1(1), pp.52–65. [Accessed 01 October 2018]

Wallensteen, P. (2015) Understanding Conflict Resolution. Fourth Edition. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Warwick, J. (2015) Black Flags. London: Bantam Press.

Written by: James Brackenbury

Written for: Dr Stephen McGlinchey

Written at: UWE Bristol

Date Written: May 2018

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Nuclear Brinkmanship in Russia Today: A Strategic Narrative Analysis

- Offensive Realism and the Rise of China: A Useful Framework for Analysis?

- Queer Asylum Seekers as a Threat to the State: An Analysis of UK Border Controls

- Terrorism as a Weapon of the Strong? A Postcolonial Analysis of Terrorism

- National Identity and the Construction of Enemies: Constructivism and Populism

- How National Identity Influences US Foreign Policy