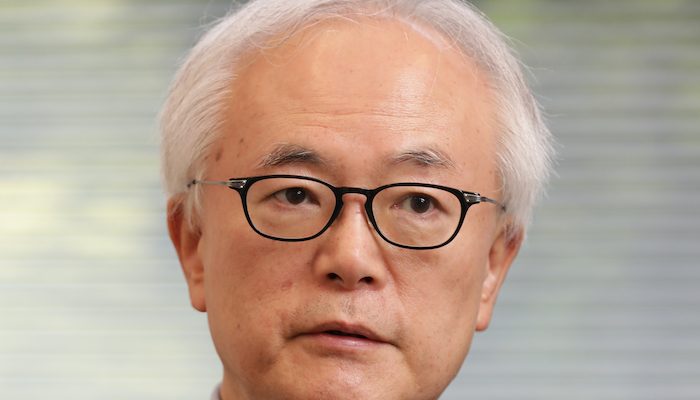

Tomohiko Taniguchi, PhD, is a Professor at Keio University Graduate School of System Design and Management and Special Adviser to Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s Cabinet. He was awarded an LL.B. from the University of Tokyo. In 2005 he joined the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as Deputy Press Secretary. He spent the next three years writing speeches for then Foreign Minister Taro Aso. Since January 2013, he has been Prime Minister Abe’s primary foreign policy speech writer. Previously he was a journalist for 20 years, during which he spent a stint in London, 1997-2000. In 1999 the Foreign Press Association in London elected him President, the first from Asia.

Where do you see the most exciting research/debates happening in your field?

In my narrowly defined field of Japanese foreign policy, I have been enthused not necessarily by research or debates but by the unravelling drama out there in the field, such as whether the Republic of Korea (ROK) and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) will merge with the North’s nuclear arsenal which is largely intact; or what will happen to US military deployment on the Korean peninsula; or what will happen to China’s snowballing debt.

How has the way you understand the world changed over time, and what (or who) prompted the most significant shifts in your thinking?

If you are not socialist at the age of twenty, you are heartless. But if you are still socialist when you get to forty, you are brainless. I recall that Winston Churchill said something like that. I was NOT heartless around twenty years of age, and NOT brainless either at around twenty-five years of age. The change came from the cognizance I gained from my former colleagues. For the first time in South Korea, labouring, not arguing and reading, earned positive value. This was in the late 1970s when Japan’s immediate neighbour was ruled by Park Chung-hee. The lesson I gained was that one should not get obsessed with one single simplified perspective but rather, one should better look at both sides of the same coin.

Also, I spent roughly twenty years with Nikkei Business, a Japanese business and finance weekly magazine. During that time, I spent a stint in London. The London-based Foreign Press Association is the world’s oldest such institution. I was fortunate to be elected its President in the late 1990s. Those experiences obviously gave me a broader world outlook, which I may say, remains important whenever I write foreign policy speeches for Shinzo Abe. As an academic, I fondly read the British School of International Political Economy (IPE) with my students.

2019 marks the sixth anniversary of PM Abe’s “Abenomics” policies. Could you explain what the policies aim to do and how they have impacted Japan’s national and international politics?

Japan is still the second largest democratically run economy. International attention gives you recognition, which can be turned into a source of your soft-power. It has been great that Japan, under Abenomics, has caught more attention from the worldwide investment communities such as Wall Street, the City of London, Hong Kong and Singapore. Many newspapers that range from the Financial Times to the Wall Street Journal run more Japan-related articles these days. The crux of Abenomics is to sow seeds of hope among the nation’s younger generations. The prolonged economic malaise that lasted more than twenty years deprived the younger generations of hope for the future, and their can-do spirit that one might consider being similar to self-efficacy. Without hope, one could grow no more and thus, one takes less and less risks. A risk-averse attitude also leads fewer people to establish families and raise children, which has the net effect of negative population growth. Abenomics has lifted the degree of self-confidence among the young. Currently, 98 out of 100 job-seeking Japanese college graduates are being employed by decent employers, with little to no debt on their shoulders. Of course, much more should be done. Also, Tokyo is hosting the Rugby World Cup in 2019, the Olympics and Paralympics in 2020, and the Osaka-Kyoto area will host the World Expo 2025, all of which also boosts the morale of the people.

How successful do you think PM Abe has been in his efforts to promote Japan and improve its foreign relations and global standing? How will the upcoming G20 Summit in Osaka and the 2020 Tokyo Olympics & Paralympics feature in these efforts?

For any country hosting the G7/G20 and great sports events such as the Olympics gives a one-off, and yet extremely cost-effective marketing and self-promotion opportunity, as the host nation receives much media coverage from around the world. One must first win the bid to be the host city in the case of the Olympics and World Expo or must be patient enough to be able to host G7/G20 meetings, as, for instance, the latter reaches you once in as long as 20 years. Being a long-serving Prime Minister, Shinzo Abe has won the right to host those events and not just by luck. He started off his second premiership at the end of 2012. For around the two-plus years that followed, the mainstream world view was that Shinzo Abe was a reactionary, ultra-nationalist, and even a war-mongering leader. Scarcely any such view surfaces any more, for the following reasons:

1) He opened Japan to more, not less, influence from abroad

2) He succeeded in reinvigorating the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TTP) that was losing its life and brought it into effect by leading the pack of 11 signatory nations

3) He exhibited his gifted talent of befriending both Barack Obama and Donald Trump – a rare talent indeed

4) He also showed his strategic mindedness by strengthening Japan’s bonds – not only with its seasoned ally of the United States – but also with Australia, India, France and the UK; essentially, democracies with a maritime identity, to secure Japan’s standing while at the same time bringing the long-tattered Beijing-Tokyo relationship into a much calmer stage.

What are your views on Japan’s current position in the Asia-Pacific with constant Sino-Japanese tensions, a more active North Korea, poor relations with South Korea, and a weaker US-Japan alliance?

My own set of presuppositions in viewing Japan’s neighbourhood is that the US-Japan Military alliance is stronger than ever before. Whatever their motives, China’s topmost leaders have, for some time, ceased to say anything nasty about Japan and instead have shown their willingness to improve bilateral ties, evidenced by the planned state visit of Xi Jinping later this year. These two factors have given Shinzo Abe intensive communication channels, especially with the President of the United States (POTUS) that is essential for Japan to deal with Pyongyang. In addition, almost all Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) are willing to work more closely with Japan. South Korea poses a distinct challenge. As for the regime in Seoul, I sometimes remember the maxim: history is your best teacher, but it can be your most horrendous master.

You recently participated at a roundtable on “Japan’s current political and economic relations with its Northeast Asian neighbors and the United States”. What are the crucial outcomes regarding Japan’s Northeast Asia relations?

What matters in one nation’s international relations is no different from what matters for you as a shop owner: location, location, and location (Mr. Trump should be well aware of this). Given where Japan is, the country could choose one way or another: a continental way or a maritime one. Under Shinzo Abe, Japan revisited and reinforced its long-standing maritime identity. Overseas — in Japan’s case, not overland — you find like-minded, sea-faring, and democratic partners that increasingly include Britain and France; both are what they call “residents” in the vast stretch of the Indo-Pacific oceans. The question concerning what would happen to US primacy in the region is not “what-if.” Is there any value in asking what-ifs in the case of the USA, like what if the US pulls out of Asia? What if the US withdraws even from Japan? The correct question Tokyo should ask itself is what could/should Japan do even more to stabilize the presence of US forward deployment. As it is Japan that can provide the US with the best possible basing facilities, even considering the ongoing problem associated with the US Marine Corps air-base relocation case in Okinawa. So, in the roundtable’s outcome paper cited above, I made the case that Japan is a stabilizing force for the US’ Asian engagement.

How will Economic and Strategic Partnership Agreement between the EU and Japan affect their relationship? You’ve argued that Brexit could turn out to be a ‘blessing in disguise’ – is this still the case?

In real terms, it stands out as the biggest and the most advanced trade and investment liberalization agreement ever forged between two advanced economies. It should thus benefit both parties. For Japan, the tall entry barrier – long maintained by France and other EU states – for Japan’s brand cars and car parts finally goes away, which is probably the best news regarding the EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA). Symbolically, it is also important. I know very well how protectionist Japan was in the 1980s. I still sometimes scratch my head looking at where my country stands, and yet, Japan can now present itself in the international arena as a primary flag bearer for the free, open, and rules-based international order. Quite a departure from its past, yes, but the successful completion of both TPP and EU-Japan EPA have strengthened Japan’s status. As far as Britain-Japan strategic ties go, the answer is still a resounding yes. I am not talking about broader economic relations. It is the state-to-state relationship I look at, and if one looks at where it stands, it is safe to say that never before has it come to be this deep and wide regarding cooperative military relationships, to take just one aspect. One must go way back to the early twentieth century to find something similar when Britain chose Japan as its first-ever alliance partner. This is a blessing in disguise for the Brexit turmoil which has urged British leaders to reinvigorate the country’s engagement in the Indo-Pacific region.

You are a professor at the Graduate School of System Design and Management (SDM). Could you explain what SDM studies involve and what is innovative about this approach?

The discipline of systems engineering came to its present-day fruition only of late. The new academic discipline, however, has its roots deep into history as its cradle was the US and European defence industries. To launch a missile, it took multi-disciplinary efforts – putting together knowledge of aerodynamics, thermopower, and electronics and so on. This gave birth to a distinct set of methodologies with which engineers designed, tested, validated and verified complex products of which failures cost millions of dollars. Blessed with well-developed, non-verbal but highly contextual communicative skills, Japanese engineers from design and manufacturing factories such as, for instance, Toyota, once succeeded in developing products which were less faulty. Now, in the age of Society 5.0, which ushers in the Fourth Industrial Revolution, one must speak with others from different backgrounds and with a different set of skills and knowledge. The discipline of systems engineering, particularly what is called model-based engineering, gives you a universal language with which you can pursue innovations more effectively. Japan has a long way to go in that respect. Why am I with such a school? Because I want to help build future leaders that are equipped not only with engineering savvy but also with a good enough sense of history. I am in that sense the school’s designated outlier.

What is the most important advice you could give to young scholars of International Relations?

As with history, one should never make mathematics your master. Susan Strange is less and less talked about one of these days. But I know she was proud of her books that her LSE colleagues often dubbed “descriptive.” I know that because I chanced to be her last interviewer before her death, and I still admire her. She was strong in grasping history. How could she turn herself into a trail-blazing pioneer in the field of IPE after raising children, as many as six? Her career tells us that it is never too late. I should say that the young scholars raised in countries such as the UK are blessed, for in those countries people greatly value reading biographies. One well-researched and vividly written biography is worth dozens of school textbooks when it comes to grasping the reality our forerunners lived under.