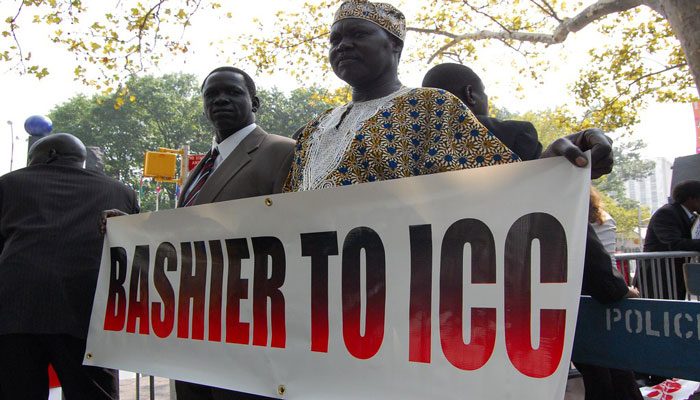

One of Omar Bashir’s last major international exploits before he was ousted from the Sudanese Presidency on 11 April was to oversee the latest iteration of South Sudan’s peace deal. The deal, first resolved in 2015, was meant to end the civil war that began in 2013, only to fail and was followed by a long negotiation. With Bashir’s removal, many are pondering the potential impact on the viability of the agreement that relied to some extent on his personal influence and funding support from Sudan and its allies.

This is, of course, not the first peace negotiation or civil conflict in what is now South Sudan. The country itself was born of Sudan’s second civil war. Importantly, there is far more continuity between early conflicts and agreements in the current situation than differences. A 2005 peace agreement between the Sudan People’s Liberation Army/Movement (SPLA/M) and Bashir’s government ultimately resulted in South Sudan’s independence from Sudan. After independence, South Sudan has struggled to escape the structures and dynamics of conflict that became entrenched during the long first civil wars starting after Sudan’s independence from Britain in 1956.

Bashir stepped in where many in the region and most of the Western members of the international community had given up and, in September 2018, shepherded the Revitalised Agreement for the Resolution of Conflict in South Sudan (R-ARCSS). Bashir had deep links with the various groups involved in South Sudan’s conflict as a key feature of the 1983-2005 war was the successive Khartoum regimes’ employment of divisive ‘divide and rule’ tactics in what is now South Sudan. Purchasing the loyalty of various armed groups in local communities and key leaders was the vehicle through which much of the war in southern Sudan was fought. This was particularly the case after Bashir came to power since before rising to the Presidency through a coup in 1989, he had been a key broker and military leader in the campaigns in the oil-producing regions that now make up Sudan and South Sudan’s border.

With the support of allies such as China, Russia, and Saudi Arabia, Bashir used resources and his influence on various armed and opposition groups to broker a deal. Although the resulting agreement is acknowledged to be replete with flaws, it is a deal none-the-less, and there has been relative stability since its signing.

That’s not to say, however, that there has been much progress on its implementation. As a major deadline for the formation of a Transitional National Government looms in South Sudan, many fear the peace is faltering. With the upheaval in Sudan and Bashir’s ouster on April 11th, many appropriately fear that without the key brokers for this agreement, an already tenuous situation in South Sudan is now bound to collapse sooner than later.

The situation in Juba, South Sudan has been tenuous for weeks as apparently there has been little progress on key elements of R-ARCSS. At the time of writing, Riek Machar, the leader of the opposition group, Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-in-Opposition (SPLM-IO), was refusing to return to Juba and take part in forming the Transitional Government, while President Salva Kiir asserted his determination to form the government with or without Machar. It seems the stage is set to replay aspects of the previously failed peace of 2015. Given Sudan and Omar Bashir’s role as the major broker that sealed R-ARCSS, the removal of Bashir, the military’s take over and the continued civilian protests have raised major doubts that Sudan can provide the shepherding peace implementation that South Sudan clearly requires.

In assessing the complicated nature of the prospects of the current situation in Sudan on the peace in South Sudan, the following looks at the role Bashir and Sudan have played in South Sudan’s politics. Situating the thinking about the impact of the transformation in Sudan on South Sudan in historical context is important as it allows a view of the nature of the relationships between the key players and the key dynamics. It also affords a view of what has changed. Through this, we can see that, despite the removal of Bashir, it is clear the senior military in Sudan and the senior leadership (of both government and opposition) have deep ties. The mutual dependency on shared oil resources between Sudan and South Sudan continues. This all points to incentives for Sudan to continue to support the South Sudan peace and facilitate the process of its implementation. However, Sudan and South Sudanese politics have a tendency to defy conventional wisdom.

Sudan and South Sudan Linked by Oil, Personality, and History

Conventional wisdom would hold that, due to continued mutual economic reliance on each other, Sudan would be compelled to continue every effort to support peace in South Sudan. Juba and Khartoum are linked through an oil economy that straddled the two states as the oil is largely located in South Sudan, and the only infrastructure to export lies in Sudan. Both countries depend on the oil as the largest component of their GDPs, with more than 90 Percent for South Sudan. Facing protests born of economic grievance, Sudan arguably needs the peace to be implemented in South Sudan more than ever to secure the oil revenue.

Sudan and South Sudan politics are far from conforming with conventional wisdom however. Localized politics, competition framed by ethnic groups, individual ambitions, community perceptions, and deep-rooted customary political economies built around patronage can confound conventional wisdom.

On the other hand, compounding the complexity, leaders in Juba and Khartoum fought a long bitter civil war, ending in Sudan agreeing to the peace which many in the security services felt was humiliating. Many resent Bashir for his agreeing to the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) in 2005, and some of these figures may now be poised to assert themselves with Bashir’s exit.

Another key consideration is the longstanding connections between senior South Sudanese leaders and Sudanese military and security officials. The very senior leadership and the old guard of the SPLA/M share deep connections with top Sudanese military leaders. A second category of relationships was formed in connection with the CPA after 2005. At the time when many senior SPLM/A leaders took on roles in the transitional unity government in Khartoum, many developed strong working relationships. Finally, a large number of those armed group leaders and opposition political figures that have challenged the SPLA/M during previous wars, the CPA period and since the South Sudan civil war, have long had relationships with Khartoum officials as they acted as allies and/or proxies of the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF).

Before the outbreak of civil war in 1983, many of the older South Sudanese leaders, such as Salva Kiir, served in some capacity in the Sudanese military. Kiir was one of the Anyanya rebels that were integrated into the SAF after the 1972 Addis Ababa Peace agreement which ended the First Sudanese Civil War. He received training and became an officer. During that time, he built numerous relationship with Sudanese leaders in spite of the later rebellion. Some of the senior staff that has now taken control of the government in Khartoum are from the same era as Kiir, including Ahmed Awad Ibn Auf, the former Minister of Defence who initially took control after Bashir’s departure. The new head of the Transitional Military Council (TMC) General Abdel Fattah Al Burhan Abdelrahman studied at the Sudan military college when the late SPLA/M founder Dr. John Garang De Mabior was an instructor.

A key feature of the second civil war in Sudan was the use of local armed groups to fight opponents, demonstrating a ‘divide and rule’ strategy. The cleavages and competitions between southern groups were as significant as the cleavage between the SPLA/M and Khartoum. Many of the leaders that currently oppose Kiir’s government were the very same leaders that fought Garang and Kiir’s SPLA/M in one way or another during the second civil war and in so doing received the support of, allied with, or formally joined, the Sudanese military. Some opposition leaders remained in the Sudanese military, such as the late Peter Gadet, who was a General in the Sudan Armed Forces and a General in the SPLA at the same time and then also rebelled from the SPLA. Many of those that would later become the opposition to Kiir’s SPLA/M government in Juba had fought against the SPLA/M during the second civil war. Other South Sudanese opposition groups’ leaders who became Sudanese military officers during the civil war still chose to accept the support of the Sudanese military to fight against SPLA/M, for example of, most prominently, leaders such as Riek Machar, and Lam Akol after their breaking away from the SPLA/M in 1991. These links were maintained and have been the source of much consternation between Juba and Khartoum as Kiir pushed for the SAF to end its support to armed groups opposing the SPLA/M, and Bashir pushed Kiir to end support to the various SPLA/M groups that remained in Sudan territory after the independence of South Sudan in 2011, for example of the SPLM-North in Blue Nile and South Kordofan.

A third type of relationship was fostered after the CPA beginning in 2005 when a number of senior SPLA/M figures were chosen to go to Khartoum to be appointed to most of the key offices including the National Intelligence and Security Service, as the peace stipulated there to be a southern deputy or joint-head in many ministries. While in Khartoum, a number of SPLA/M figures cemented longer relationships based on the above or built new connections.

These three types of relationships between the Sudanese military/security establishment are now increasingly significant with the emergence of the military and security establishment as the primary broker of power in Khartoum.

Meanwhile, since the use of paramilitaries and militia allied to the Khartoum government in security and counter-insurgency efforts have long been institutionalized in the Sudanese security apparatus, which has become the domain of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) over the last ten years, the inclusion of the figure in charge of the RSF in the transitional committee may indicate another dimension of impacts on armed groups’ commitment to peace. The RSF is a catch-all entity that coordinates and leads the various paramilitary and allied militias that the security services and military utilize to carry out often brutal security operations throughout Sudan, the most notable being the Janjaweed in Darfur. The RSF became important elements in conflicts in Sudan’s regions like Darfur, South Kordofan, and Blue Nile, their precursors operating throughout southern Sudan. The head of the RSF, Mohammed Hamdan Dagolo, is now the deputy head of the military transitional committee and interim vice president.

The precursor of the RSF directed, funded and supplied a range of southern armed groups against the SPLA/M from 1983 to 2005, for example of the factions of the South Sudan Defence Forces (SSDF) to implement the strategy of ‘divide and rule’. As a result, the relationship between the various former proxy forces in South Sudan and the officers that formerly were the key connections between southern armed group leaders and Khartoum security services is now especially relevant. This includes prominent figures in South Sudan including Riek Machar who on a number of occasions agreed to coordinate with Sudanese military and political organs against the SPLM/A.

With such a central role of the RSF in the direction of the wide range of paramilitary and militia throughout Sudan, the inclusion of the head of the RSF in the upper echelon of leadership presents apparent opportunities for southern armed group leaders to engage individuals they know. With their key brokers now in a central role in government, the leaders of the various militia and paramilitaries will more likely than not find renewed significance and at the very least perceive new avenues to assert their interests. Most worryingly, this may result in an increased perception that asserting oneself as an armed group in South Sudan could find support from Khartoum should the government in Juba not agree to include them in the peace process and transitional governance and security arrangements of R-ARCSS. This may potentially contribute to undermining the relatively stable situation where the two governments had committed not to provide support or political cover to the insurgents operating just across borders inside each other’s countries.

Political Upheaval in Sudan and its impact on South Sudanese Opposition

The alternative view to the conventional wisdom is that the turmoil in Sudan remains unresolved and likely to continue for some time. It is becoming abundantly clear that in Khartoum, the focus and capacity of the leaders are directed at internal issues. This means at best the peace in South Sudan will be left with little outside direction and support, bearing in mind that the international community (that is Western states and international organizations) had largely backed away from the process. More delay to R-ARCSS implementation is likely to lead to positioning and maneuver efforts by both South Sudan’s government figures and those from the opposition groups. Meanwhile, the key players in Khartoum are at least not in a position to maintain their influence over a range of the various armed groups, which make up much of Riek Machar’s SPLM-IO contingent, who at the time of writing appeared to be struggling with internal coherence.

Facing internal SPLM-IO cleavage, expressing security fears and citing poor resourcing, Riek Machar has proven unwilling to return to Juba and take up a role in the Transitional Government, a key step in the implementation of the peace, and demanded a six-month extension. Bashir’s apparatus had long been brokers with Machar and his associated forces. As previously explained, Bashir had influence because he and his senior military had employed Machar and various other opposition leaders as proxies during the second civil war and thereby maintained influence, with many remining in SAF or continuing to receive financial and material support. Since Bashir’s ouster and the military takeover, leaders in Khartoum appear unable or unwilling to provide the guarantees and resources Machar is looking for, and Juba is not likely to be able to provide what he is requiring, even if a six-month extension were agreed.

In relation to new individuals asserting power in Khartoum, the balance of power in South Sudan may also be shifting, which will impact the implementation of R-ARCSS. A range of opposition figures are politicking heavily, looking to leverage their relationships with the new powers in Khartoum. For example, the numerous political and armed group leaders, such as Taban Deng Gai, Gatkuoth Gathoth, Johnson Olony, have challenged Kiir’s government under the banner of the SPLM-IO and in their own right as well.

These figures are reportedly working to secure themselves and their groups in relation to the emerging dispensation in Khartoum. For example, some are now asserting themselves after the recent death of the powerful opposition military leader Peter Gadet. Some appear to have stronger relationships with the new senior military figures than Riek Machar himself. At the time of writing, there have been active and hurried efforts afoot by these alternative opposition leaders to leverage their relationships and secure their own emergence as Machar faces uncertainty and cleavage in his own camp, further deepening the challenge of anyone committing to a Transitional Government and moving forward on the practical implementation elements of R-ARCSS. It is not implausible, for example, to see Taban Deng Gai return as the main opposition figure in a Transitional Government in South Sudan, similar to the way he stepped into the role of Vice President after the 2015 peace agreement which effectively split the SPLM-IO, with Riek Machar and others continuing to struggle against Kiir and the government in Juba.

Juba Supports Whoever is in Power in Khartoum

As protests strengthened in Khartoum through February and March, Salva Kiir expressed support for the now deposed and imprisoned Omar Bashir. Shortly after Bashir’s was removed from office, Juba’s envoy to Khartoum, Tut Kew, formally congratulated the new military leaders. With those leaders handing over to new military leaders and talking with political parties to form a government in Sudan, Juba is offering support to whoever takes the reins in Khartoum.

This rapid switching of loyalties may seem fickle, but President Kiir and the government in Juba had little choice to first support Bashir and then indicate their support for the new powers in Khartoum. Regardless of who is in power, Kiir relies on Khartoum’s support to undermine the threats posed by opposition groups.

Since South Sudan’s independence, Bashir and Kiir accused each other of supporting armed groups in each other’s states. The two leaders expressed intent to end respective support to insurgent armed and political groups in each other’s territory. Combined with the same commitment by regional leaders, the security dynamic had become less tenuous. This led to opportunities for government in Juba to more effectively assert itself as the sovereign authority. With Bashir’s ouster, this deal, along with many other agreements between the leaders, is in question.

Although Kiir and South Sudanese leaders have long and sustained relationships with many in the Sudanese military now in control in Khartoum, it was Bashir who drove the agreements with Kiir that in some instances ran counter to the interests of some in his own inner circle. The survival of these agreements raises important challenges to the peace process in South Sudan. With new lifeblood or support from neighboring leaders, various opposition groups could see value in acting as spoilers to the peace or at least believe it viable to challenge a deal that many amongst opposition groups and leaders dislike and regard as too much of a surrender.

Prospects, Contradiction, and Confusion

As is so often the case in Sudan and South Sudan, the politics contain a mixture of often competing and contradictory elements. With respect to the potential impact of the current revolution in Sudan on the South Sudan peace process, the underlying features suggest it should not change the situation radically. However, the dynamic politics involving personalities and the apparent tendency for Sudanese leaders to focus inwardly when facing such domestic upheaval suggests the peace will be negatively impacted.

Seen together, prospects are likely that the situation in Sudan will result in less pressure and resourcing for the peace process to move forward in South Sudan. The uncertainty and exacerbated maneuvering of various armed and political leaders from South Sudan is likely to further complicate matters. The confusion will likely cause further delays in key implementation milestones, most importantly, the security arrangements and the formation of the Transitional Government. Without the action by regional parties and/or Sudan, if the Transitional Government is not formed, the R-ARCSS may collapse. At the time of writing, indications are that Riek Machar will reject forming a Transitional Government and a range of newer figures will jockey for influence in relation to the transition in Khartoum.

The underlying force of the need for Sudan and South Sudan to find a way to maintain some kind of stability sufficient to keep oil flowing will see renewed effort, likely with backing and active engagement by China and Russia. With other international actors remaining on the sidelines, Sudan’s role in facilitating the progress of R-ARCSS, or not, will prove important. If domestic focus precludes any engagement in South Sudan, the situation for Juba and Khartoum is likely to worsen as both stand to lose much of the oil revenue. In such an eventuality, we are likely to see the Sudanese economy struggle with the continued rising of prices, the very thing that set-off this round of protests. Without the oil revenue and active engagement by Khartoum, Juba will struggle to fund the patronage structures that allow Salva Kiir to continue governing and certainly preclude their ability to fund implementation of the peace.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Self-Determination as a Process: The United Nations in South Sudan

- The Fall of Omar Bashir in Sudan: A People’s Revolution or a Changing of the Guard?

- The Internal Displacement of People in South Sudan

- Opinion – The Sudanese Conflict and the Abyei Dispute

- Resilience Governance: A New Form of Colonialism in the Global South

- Unseen Frontlines: Narratives on Sudanese Women in War