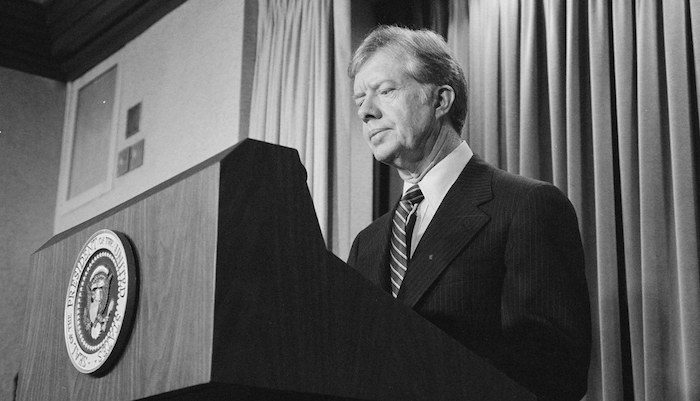

US President Jimmy Carter took office in 1977, armed with a set of liberal ideals and aspirations that he believed would revolutionise American foreign policy. Carter had strong convictions that it was timely to initiate overhauling reforms in the country’s foreign policy by advancing human rights globally and pursuing a policy of arms restraint. During the onset of his regime, many administrations in the global landscape were dictatorships that committed human rights violations and were hungry for advanced armaments the US could offer. Carter meant to resolve this situation by infusing humanitarian concerns into the US foreign policy and implementing reprisals against governments that engaged in human rights abuses. Another ideal Carter romanticised about was disarmament, reduction of arms sales overseas (especially to none NATO nations), and non-proliferation of nuclear weapons. Going as far as making the sales of arms to foreign nations something that was done on an ad hoc basis. Carter believed that the time had come for the United States to move past Cold-War tensions and alter the US’s approach to containment in spite of Soviet determination to proliferate communist ideology on a global scale. As noble as they were, in practice Carter’s ideals crumbled due to his double-mindedness and want to compromise to please multiple parties. His liberal policies such as advancing human rights, democracy and education globally crumbled against an embedded strategic realpolitik policy set of deeply embedded policy packages, such as the Nixon administration’s policy of arming the Shah. This caused Carter to cave to the pressure of grander Cold War containment policy, which underpinned US foreign policy during the Cold War.

The purpose of this paper is to offer an in-depth analysis of Carter’s foreign policy on human rights and arms, using primary and secondary sources. It will aim to illustrate the main reasons why Carter’s foreign policy is largely considered a failure following his re-formulation and the impact that his posture had in these areas. To be precise, the discussion and analysis covers the differential way in which Carter ended up coercing nations into advancing human rights and the idealistic posture he had towards human rights and arms. For example, funding authoritarian dictators such as the Shah of Iran, via arms donations and sales and training of his ruthless internal police, the SAVAK. However, abiding by a stricter policy when facing less geopolitically important states, thus Carter’s foreign policy unraveled in a paradoxical way. Although the analysis of this paper is based on Carter’s foreign policy, rather than theories of international relations, the importance and relevance of realist and liberal theories will be utilised in order to underpin the central argument that Carter, as a true liberal who believed in arms control, human rights and free markets and societies was forced into conforming to the realist dominated tensions of the Cold War. This will provide wider contextual understanding and offer a deeper insight into Carter as an individual and the effects this had on US foreign policy.

Chapter 1 – Jimmy Carter’s Human Rights Policies and Practices

In 1977, Jimmy Carter’s administration embarked on a noble mission to elevate human rights considerations into American foreign policy. Carter entered office with the deep conviction that liberalism was the best way to champion human rights and to counter Russia’s geopolitical assertiveness. In his inaugural address, Carter articulated that the country’s “commitment to human rights must be absolute” (Carter, 1977) and setoff to fulfil this mandate. The president believed that the best way to champion human rights was to reshape the US foreign policy entirely, following liberal ideals. Carter was desirous of a global landscape where authoritarian regimes would be replaced by democratic regimes, an ideal that would follow on long after Carter’s tenure. This was a bold move away from traditional containment pursuits, which only served to divert attention from widespread human rights violations across the world whilst enhancing U.S geopolitical interests. Needless to say, Carter’s administration was set against the backdrop of Soviet carnage, communist uprising and high geopolitical stakes. Carter took the moral high ground and maintained that his administration would not prioritise strategic geopolitical interests over human rights. The president believed, “arguably naively, that the idealistic nature of his human rights policy would overcome issues of the inherently realistic pursuit of national interests” (Willis, 2014, p. 10).

As the president later wrote in his memoirs,

“I was familiar with the widely accepted arguments that we had to choose between idealism and realism, or between morality and the exertion of power, but I rejected those claims. To me, the demonstration of American idealism was a practical and realistic approach to foreign affairs, and moral principles were the best foundations for the exertion of American power and influence” (Carter, 1982, p. 143).

Carter shunned the conventional way of tackling human rights concerns across the globe and perceived, correctly, that the pursuit of realism came at the expense of human rights. As geopolitical interests are rare to merge directly with those of human rights. His predecessors typically issued strong statements to criticise nations and administrations whose practices were inimical to people’s inherent human rights. For example, the Eisenhower administration attempted to prevent large-scale wars such as the Korean War, which would have violated multiple civilians’ human rights. However, he did so from a strategic point in order to save the U.S. economic resources and direct ‘boots on the ground’ symmetric containment, opting for an asymmetric approach to foreign policy. Carter however wanted to make human rights the dominant goal, not a second-tier issue.

The traditional posture demonstrated by Carter’s predecessors was founded in realism whose key propositions claim the state should seek survival and status via the acquirement of military power and geopolitical interests. Carter thought differently and believed that the US could leverage different approaches to achieve foreign policy goals. His strong conviction was that it was necessary to back the stern presidential statements with suitable reprisals that would give foreign administrations an incentive to desist from human rights abuses. His new strategy entailed deploying a mix of diplomacy, aid reductions as well as reduced military support. The expectation was that taking such as hard posture would ultimately pressure nations into adhering to the requirements imposed on them by the United States.

As a start, Carter sought the inclusion of additional voices in policy formulation and revived the defunct Humanitarian Association in the State Department. The Humanitarian Association was first established during Gerald Ford’s administration, and its primary mandate was to integrate humanitarian issues into the country’s foreign policy formulation. This change registered some notable successes as the administration reduced the degree of military assistance afforded to dictatorial regimes in Latin America. Carter also transformed the way his administration framed the country’s policies by requiring the consideration of moral as well as humanitarian concerns (Snyder, 2016, p. 4). Evidently, there was some merit to Carter’s approach, but it was the double-minded way in which he pursued this goal that unraveled his plan. For example, his efforts in Latin America the amount of human rights abuses decreased due to Carter applying a hardline stance. In Iran though he sacrificed this hardline policy to pander to geopolitical interests. Carter also appointed advisers with differing convictions on human rights and the importance of geopolitics, such as Zbigniew Brzezinski as National Security Advisor who was much more concerned with geopolitical gains than moral concerns such as human rights. Brzezinski held similar ideals to hardline realpolitiker, Henry Kissinger who previously held office of National Security Advisor. Carter’s Secretary of State, Cyrus Vance, was far more focused on the moral change for human rights that Carter imposed as his new foreign policy approach and less concerned with the traditional geopolitical interests of containment policy. In this way, the president set the stage for what would be an incredible and confounding patchwork of disparate policies that stalled his humanitarian efforts.

Carter assigned equal influence on the proponents of integrating humanitarian concerns into US foreign policy as well as traditional realpolitik foreign policy ideas. The critics, such as Brzezinski felt that focusing on human rights would divert the administration’s efforts and resources from other pressing developments such as the containment of the Soviets. This problematic foundation was merely a precursor to greater hurdles that lay ahead. Sharply conflicted voices behind the president stalled decision-making processes. For instance, Brzezinski who favoured the prioritisation of Russia’s containment and geopolitics faced off with Vance who supported the president’s intent to integrate humanitarian concerns into US foreign policy (Murray, 2010, p. 14). Brzezinski gained dominance over Vance as he did not quiver from political standoff that the U.S. was grid locked in via Cold War bipolarity. Highlighting the ease of the trap Carter began to fall into which was characterised by listening to the traditional already established hard line realpolitik approach to foreign policy, which many of his predecessors did.

The first concern with regards to Carter’s policy of cutting aid to nations was characterised by widespread human abuses and the differential manner in which he applied this reform. It soon became apparent that Carter was quite selective in the way he dispensed reprisals against so-called errant nations. Apparently, there were exceptions to Carter’s “absolute commitment to human rights” as some countries were not treated any differently despite committing human rights atrocities. For example (as will be unpacked below) Carter’s absolute commitment to human rights did not waiver when addressing less strategically important regions such as South America and his new approach was able to enjoy success. Whereas, with regions such as the Middle East, which housed nations such as Iran proved impossible to pursue this absolute commitment to human rights as the geopolitical interests were impeded far too deeply to risk upsetting or removing them in exchange for human rights interests.

Carter’s Latin America Foreign Policy

In 1977, Carter cut down military assistance as well as arms sales to select countries such as Chile, El Salvador, Uruguay and Argentina under the guise of forcing them to adhere to international human rights policies. Carter’s human rights policy towered over Latin America as he perceived that the threat posed to US geopolitical interests by the region was minimal. The administration military funding to Latin America reduced by 75 percent from $233.5 million to $54 million in 1976 and 1979 respectively (Kaufman, 2008). Although this military funding consisted of arms sales and more general preservation of the region to keep it out of Soviet reach, it had a large impact for human rights. As multiple leaders in the Latin American region toed the line and checked humanitarian abuses, even setting off the implementation of democratic governance.

For instance, Argentina was under the leadership of a Military Junta at the time, and the scale of human rights abuses they committed was worrisome (Clymer, 2003). The disappearance of Argentinians under the Military Junta’s governance was the main factor that drove the Carter administration to reduce military funding to the country. The president insisted on a shift to democratisation as a precondition for lifting the measures. Even so, he was unwilling to go as far as banning the sale of pipeline goods as proposed in a Senate bill in 1977. It is worth mentioning that major strategic assets that could be leveraged against communist interests were not at stake in the case of Argentina, Uruguay, and Chile. As a result, Carter maintained an unwavering stringent posture against the countries. In El Salvador, Carter was forced to reinstate military aid to quell the impending threat of a revolution in the nation, which perpetuated yet another authoritarian regime.

Elsewhere, Carter took a more lenient stance especially in regards to countries that he perceived as either strategically important or nations that posed a high national security risk if tampered with. His posture towards Nicaragua’s then authoritarian president Anastasio Somoza Debayle was entirely different from his initial humanitarian convictions in spite of the human rights atrocities committed under his regime. Carter quickly took up Brzezinski’s suggestion that meeting reprisals against Anastasio would be inimical to halting the proliferation of communism in the region. A communist guerrilla movement known as Sandinistas had burgeoned in the Nicaraguan political scene and was an indicator that if the group continued unabated, they would topple the authoritarian administration and align the country with Russian communism. As a result geopolitical influence took the fore over humanitarian concerns in this case. Aamose faced no punishments from the U.S. Instead, the U.S. government armed the dictator to enable him to quell the guerrilla group. Policymakers considered the political crisis that later culminated in the fall of Somoza in the summer of 1979 to be a greater priority than the advancement of human rights (Jones, 2015, p. 216).

Carter’s reluctance to fully follow through with the absolute commitment was becoming less clear to the international stage. Creating a patchwork rather than a neat weave between human rights policy and practice. The measures Carter intended to leverage to stop human rights abuses were morphing into avenues to secure the country’s strategic interests. The Humanitarian Association’s role in informing foreign policy became less meaningful as geopolitical considerations took centre stage. The administration principally focused on curtailing communist proliferation. The institutional changes implemented by Carter’s administration to drive human rights causes were far greater than the ones initiated by his predecessors. However, the pressure of Cold War realist tension was taking an increasing toll on Carter’s unwillingness to follow through with his undertaking fully. This crippled the attainment of significant traction globally regarding advancing human rights and human dignity.

Carter opted to make deals with errant administrations that repressed their citizens in an effort to curb the communist tide and imposed sanctions on other nations where he perceived that the country’s interests would not be harmed. Latin America serves as a great regional illustration of his highly inconsonant endeavor. Cutting military aid to nations such as Brazil and Argentina yielded significant humanitarian milestones in these countries while siding with the authoritarian Nicaraguan regime to prevent a possible revolution by a communist guerrilla meant turning a blind eye to widespread human rights abuses. This disparate posture was a bid to maintain the country’s dominance in geopolitics as espoused by Brzezinski. As a result, Carter produced a highly inconsistent and inefficient foreign policy that involved the abandonment of the noble pursuit to advance human rights as his administration expended its efforts on containment and securing strategic geopolitical interests.

Carter’s Human Rights Approach in China & South East Asia

Carter chose to be lenient towards China even though human rights abuses were rife within the state. Since China became communist in 1949, diplomatic channels were all but non-existent between the US and China. The two countries had fought one another in proxy format during the Korean War and were certainly not open to communication. However, in a shock move by former president Nixon, when he travelled to China on a diplomatic visit in 1972 reopening the diplomatic lines of communication between the two nations. In doing so Nixon thrust a tension and played on an already shaky relationship between China and the USSR, attempting to plant seeds for further distrust between one another.

The Carter administration’s pursuit of normalisation in China was continued after the former president Nixon travelled to China on an official state visit in 1972 which successfully reopened diplomatic channels with the communist giant. The policy aimed to treat and communicate with China like any other state, reversing the tensions and lack of communication between the two powers previous to this. This put an end to Carter’s original stance that human rights protection was a compulsory precondition to any engagement with the United States. Carter had successfully championed the policy of normalisation when following months of secret negotiations, the United States and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) announced that they would recognise one another and establish official diplomatic relations. ‘The United States of America and the People’s Republic of China have agreed to recognise each other and establish diplomatic relations’ (Carter, 1978).

Showing that a good relationship with China for strategic gain had far greater appeal than the human rights agenda that his administration had started to pursue in other Asian countries. Consequently, Carter moved to acknowledge the Chinese government and Taiwan as a part of China, ‘There is but one China, and Taiwan is a part of China’ (Carter, 1978). In doing this Carter left abandoned Taiwan’s hope for international support for its sovereignty and independence. Instead his administration left Taiwan to the mercy of China where the US had intelligence that human rights abuses were rife. In Cold War realpolitik fashion Carter choose geopolitical U.S. gains via a more positive relationships with China. Using this as a tool to install mistrust and skepticism between the Chinese and the USSR. The U.S. gained strategically from this choice, in Carter’s speech on normalisation with China he noted, “China plays already an important role in world affairs, that can only grow more important” (Carter, 1978). In the same speech, Carter noted China’s rising power and high population was only “reality” and that it was in “normalisation …. will contribute to our own national interest” (Carter, 1978).

Carter gave a televised speech where he revealed that the United States and Communist China had covertly and abruptly opted to put an end to the decades of warlike estrangement (Olson-Raymer, n.d., para 15). The initiative was championed by Brzezinski and Vance who conducted an official visit to the People’s Republic, keen on normalizing diplomatic relations between the nations. At the time, the Chinese faced considerable pressure from Moscow as well as Soviet-influenced Vietnam. Convinced that the United States could leverage the incremental tension between the two nations, Carter’s administration gave assurances to China that the US would maintain a strong presence and involvement in the Asian continent to limit Russia.

On the South East Asian frontier of the Cold War, Carter began restructuring containment with China as centrepiece for the region. China’s importance to the administration quickly escalated as human rights violations that typified authoritarian regimes in East Asia were abandoned all too easily. It sufficed simply that the United States would gain strategic geopolitical traction with the Republic of China on its side. For the U.S., China’s strategic geographic position would act as a physical barrier against the Soviets from East Asia as well as Pacific countries. China had since declared the Soviet Union as its archenemy (Metzl, 2016, p. 87). China also considered the normalisation process favourable because maintaining ties with the US would help thwart Vietnamese and Russian pressures on the Republic.

Initially, Carter’s foreign policies in China and South East Asia integrated humanitarian concerns. This yielded some successes such as Indonesia’s release of political prisoners as well as the promise of democratic suffrage in the Philippines. In Indonesia, the Humanitarian Association managed to obtain Haji Mohammad Suharto’s agreement to grant 30,000 political prisoners their freedom (Clymer, 2003). The U.S. also persuaded the Filipino regime to permit democratic suffrage in the country (Kaufman, 2008). Other than that, Carter took a hard stance with regards to South Korea and intimated that the United Stated troops, which comprised 5% of South Korea’s military, would be withdrawn over human rights violations (Dobson and Marsh, 2006).

The Asian nations, however, quickly subverted these requirements. In the Philippines, for instance, President Ferdinand Marcos executed an election that was fraught with irregularities and arrested as well as intimidated his opponents openly (Kaufman, 2008). Marco’s also moved to limit the Humanitarian Association in the country to reduce the degree of influence to human rights issues would have on his talks with the U.S. Instead, the talks majored on the vast military bases that the U.S. had in the Philippines (Kaufman, 2008), and Carter felt disinclined to jeopardise this tactical advantage over human rights concerns. In Indonesia, the U.S. gained success in the release of thousands of political prisoners. However, the Carter administration supplied arms to Indonesia following the East Timor’s invasion in 1978 and the slaughter that took place there was genocidal (Simpson, 2009). He also opted to repudiate his initial threat to withdraw American troops from South Korea. Evidently, Carter’s emphasis on the preservation of human rights and dignity in East Asia did not produce any lasting outcome due to his inconsistency.

Carter’s Human Rights Approach in Iran

Iran is the pinnacle example of Carter’s exception to his ‘absolute’ commitment to advance human rights. Iran and the United States were close allies prior to the onset of the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Carter depended heavily upon Iran to further Containment within the Middle East. The working relations between the U.S. and Iran dated back slightly before the joint CIA and MI6 engineered coup d’état in 1953 which installation the Autocratic Shah of Iran (Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi) who was more than willing to maintain close ties with the United States (Gasiorowski, 2013). Even so, a successful revolution led by Ayatollah Khomeini in 1979 threatened the political landscape in the Middle East as well as Iran’s posture regarding Russia. Iran had a strategic geographical importance as it bordered the USSR making it vulnerable to communist invasion. Iran is endowed with rich oil reserves, access to the Persian Gulf and large amounts of desert and mountain ranges, the largest being the Zagros mountains. These factors made Iran the ideal state for the U.S. to make their Middle Eastern centrepiece for offshore containment.

Fundamental to this Iran centric strategy was the need to maintain sound diplomatic ties with Israel. As the Shah of Iran viewed Israel as a progressive state (as he believed Iran was) and neither Iran or Israel would wish to for themselves or the U.S. to develop closer ties to Arab nations. Consequently, perpetuating sound diplomatic ties with Iran had greater appeal than advancing human rights. Carter, therefore, prioritised the continuation of a strategic working relationship between Washington and Tehran and again feigned ignorance of the abuses perpetrated by the Shah of Iran. The Shah had initially given the indication that he would undertake human rights reforms during the 1976 U.S. electioneering period. He even went so far as to permit nonprofits and charities like Amnesty International to enter Iran and examine the extent of human rights abuses in the country (Trenta, 2013). The Shah’s relaxation of dictatorial policies made the opposition increasingly vocal and even led to the emergence of nascent political parties like the Radical Party, which opposed his regime (Pollack, 2004). However, these were mere opposition parties, as Iran remained a one-party state.

In any case, it was an indicator that the Shah, as an autocratic dictator, was willing to be more lenient to the opposition than he had been in the past. Another encouraging move by the Shah entailed removing some hardline advisors as well as his premier in favour of candidates who were liberal to try and ameliorate the advancement of human rights in Iran (Pollack, 2004). Carter’s continuous reiteration that the United States will infuse human rights considerations into its policy led the Shah to believe that Iran would not be exempted in the imposition of punitive measures to abandon authoritarianism. Fearing that Carter’s administration would refuse to support him, the Shah rolled out some lenient policies in a bid to court Carter toward a solid pro-Iran stance. Carter never actualised his undertaking sanctions against administrations that failed to curb or advance human rights abuses in Iran’s case. The reprisals that the Shah feared did not come into fruition. Carter’s inconsistency in touching on human rights as it related to Iran soon became clear as the Shah realised that his attempts to unwind authoritarianism if only to suit the US leader’s interests were unnecessary. Arms, oil and economic dealings between the nations continued unperturbed as Carter’s administration wilfully overlooked the human rights atrocities committed by Iran’s despotic government. It sufficed simply that non-interference with Iran’s internal affairs was a means of safeguarding the United States’ geopolitical dominance.

While it is true that Iran was strategically monumental to the United States, Jimmy Carter overplayed the risk of losing the country over criticisms concerning human rights abuses. Indeed, the nation’s geographic proximity to the USSR coupled with the fact that it’s land mass served as a buffer between the Soviets and their ally Iraq meant that good relations with Iran were key to the stability of the Gulf (Murray, 2010; Kaufman, 2008, p. 153). Continued access to the vast oil reserves in Iran was also material (Kaufman, 2008, p. 153). It is also true that Iran housed critical highly advanced sites for electronic-based intelligence collection that permitted the US to gather intelligence on Moscow’s ballistic missile trials (Pollack, 2004). Admittedly, the risk of losing the intelligence sourced from these sites would have been highly injurious as the Carter administration feared (Pollack, 2004). Despite this, Carter’s failure to leverage the Shah’s anxiety regarding fears that the Carter administration would impose sanctions on Iran was his main undoing regarding advancing human rights in the nation.

Before the onset of Carter’s presidency, the Shah moved swiftly to relax his authoritarian grip over the nation to the extent that opposition parties budded and humanitarian non-profits set up an office in Iran. As Carter’s presidential campaign reiterated the importance of human rights in foreign policy. There was very limited indication that the ruler would switch sides entirely and opt to pledge his allegiance to the Soviet Union. He had an incentive to maintain close ties with the United States, which helped him suppress the same communist guerrilla problem that most pro-Western administrations were facing. The Shah had already started to put in place strategic structures to appease the US leader, but it soon became evident that his efforts were futile. Carter exempted Iran from the hard posture he had taken toward Latin America thereby letting the Shah realise that Iran was so valuable to the United States that its poor human rights records would not be taken into account.

Iran is a good example that some consistency of Carter’s part would have gone a long way into increasing the strides in human rights advancement that he longed to actualise. At best, the recognition of Iran’s value should have gone as far as affording the country some leniency in the application of punitive measures. Carter had the opportunity to convince the Shah to loosen his dictatorial grip over the nation however, Carter was not successful in this. If Carter was able to deliver, it would have been a win-win situation where the Iranian people would have received a reprieve from constant violations, and the diplomatic ties between the nations would not have been severed. From the vantage point afforded by four decades since Carter’s presidency, it is disconcerting how the administration failed to read accurately into the Shah’s initial posture and take advantage of it by bringing in human rights considerations.

Implications of Carter’s Differential Advancement of Human Rights in Iran

It is interesting to note that Carter strengthened authoritarian administrations that committed the human rights violations that he purported to fight elsewhere. Carter deemed his differential actions rightful as he at least managed to bring about as much progress in human rights as was possible to keep the United States from losing its geopolitical influence. Focusing on what was advantageous about Carter’s moves at the expense of human rights can cloud one’s judgment of what his support for autocratic governments in the respective countries meant for the citizens. This then begs the inquiry as to what situation Carter saw in these nations that prompted him to make his original ‘absolute commitment’ in the first place and what his shaky posture meant.

In 1975, the Shah made Iran and one party state (Mousavian, 2014) and controlled most facets of the country’s civil society via the ruling party, which was known as The Resurgence Party (Pollack, 2004). He used his covert police force, SAVAK, to suppress the opposition. SAVAK spread terror throughout Iran and tortured as well as executed the Shah’s opponents brutally (Pollack, 2004). Jones (2015, p. 411) affirms this by noting “SAVAK ruthlessly cracked down on political dissent against the regime, denying an outlet for dissatisfaction against the regime”. The U.S. continued to fund the SAVAK as it maintained stability for U.S. offshore interests, but that did not mean that the U.S. approved of the SAVAK’s actions. In the meantime, the CIA continued to work closely with SAVAK in spite of their brutality against the people of Iran. This reality was a far cry from the president’s directive that his administration would not align itself with autocratic governments.

Aside from the extreme brutality demonstrated by SAVAK, a wide array of economic issues weighed down on Iran’s population because of the Shah’s obsession with acquiring weapons. Trenta (2013) affirms this statement by noting that the ruler’s fixation on weapons and advanced military equipment strained Iran’s economy. This was further aggravated by high inflation rates and corruption (Trenta, 2013). As a result, most Iranians languished in abject poverty with 20% of the population depending on state handouts for survival (Pollack, 2004). The substantial income that accrued from the sale of oil was not enjoyed by the country’s citizens (Jones, 2015, p. 411). Illiteracy, unemployment, poor housing, and lack of access to proper health care diminished the Iranians human dignity, but Carter looked the other way and backed the Shah openly. Carter went as far as to publicly toast the Shah on New Year’s Eve of 1978. As he stood by the Shah’s side whilst attending a celebration as an esteemed guest he deemed, “because of the great leadership of the Shah. Iran is an island of stability in one of the more troubled areas of the world” (Offiler, 2015. p. 156).

In the meantime, widespread discontent brewed across Iran. The breaking point over the Shah’s suppression was the publication of an article in an Iranian newspaper that was slanderous of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, an exiled Shia cleric who was a symbolic figure around which the Shah’s opposition coalesced (Jones, 2015, p. 411). The article sparked violence for the remainder of 1978. The police met protests with severe brutality, but the killings did not deter protests. Instead, more agitators ganged together to honour the deaths of the martyrs, fuelling further police brutality. Unfortunately, the administration was slow to realise the severity of the ongoing crisis and thought that the Shah had the turmoil under control (Jones, 2015, p. 411).

The stark contrast in policy leanings that underpinned Carter’s administration between realpolitikers like Brzezinski and moralpolitikers like Vance stalled the response of the United States. The administration was caught up in a sharp conflict of whether to view “Iranian affairs through the lens of human rights concerns” or as a “prism of geopolitics” (Jones, 2015, p. 411; Kaufman and Kaufman, 2006, 155-158). Neither side could conceive the possibility of a “regressive revolution,” which was the eventual outcome that led to Khomeini’s reign and subsequent establishment of a virtual Iranian theocracy (Seliktar, 2000, p. 123). Carter’s double-mindedness and an impossible patchwork of liberal positions contrasted by inimical realpolitik failed as Khomeini rose to power and established a virtual authoritarian theocracy that would perpetuate additional human rights abuses. Showing that Iran was the pinnacle example of the ‘tail wagging the dog’ when it came to geopolitical interests trumping Carter’s human rights agenda, a vital and popular part of his successful presidential campaign success in 1978. It is also worth noting that Carter’s human rights policy not only resulted in losing Iran but that the next regime in Iran, a theocracy which still holds power today, meant that carter’s policies left a significant wake of human rights abuses in its path.

As Beinart (2006, para 5) so succinctly articulates, “Carter’s foreign policy is widely considered a failure”. Unfortunately, his attempt at advancing human rights instead of containment failed incredibly. He only managed to register some success in dispersed areas such as Latin America and other nations that did not have a great geopolitical importance. Afterward, it would seem the president strived to fit into the conservative refrain and consequently, “Jimmy Carter never met a dictator he didn’t like” (Renouard, 2015, p. 496). For Carter, the continued allegiance of authoritarian governments became indispensable. As a result of this, Carter and his administration opted to look the other way as they perpetrated serious atrocities against their citizens.

Chapter 2 – Jimmy Carter’s Arms Policies and Practices

High expectations, contradictory aspirations, and tactical errors infused Carter’s approach to arms sales and nuclear nonproliferation across the globe. As a staunch believer of arms restraint both in foreign policy and domestically, the president aspired once more to lead the world in abandoning conventional ways surrounding arms sales. The reduction of the scale of arms dealing pursued by the Carter administration were relevant to humanitarian considerations. Carter ascended to the presidency of the United States with the firm conviction that cutting back arms supply was an important way of coercing authoritarian nations into abandoning practices and laws that undermined human rights. Another key humanitarian concern was that the global arms race was inimical to lasting global stability. Carter found the speed at which nations especially Third World Countries strived to build their military capacities at was very fast and hard to keep in check. After all the global arms race that the two superpowers were locked in served as a trigger for the rest of the international system to gain as much power as possible via military build up. Creating an insatiable global demand for increasingly advanced weapons and military technology that Carter found particularly disconcerting. His campaign undertaking was that he would lead the world into an entirely different direction, once again negating key realism propositions. As a result of holding liberal ideals Carter saw different, believing that nations did not understand what was best for them and once again set himself up for great difficulties in executing his moralist principles. Such as persuading nations to peruse a path of open discourse and diplomacy instead of confronting one another through military tension and conflict in the thick mist of the realpolitik Cold War era.

Carter’s Proposed Policies on Arms Sales

In 1976, then-governor Jimmy Carter announced, “I am particularly concerned by our nation’s role as the world’s leading arms salesman” (Klare, n.d.). He further asserted, “The United States cannot be both the world’s leading champion of peace and the world’s leading supplier of the weapons of war.” Therefore, he gave his undertaking that if he became the US president, he would “increase the emphasis on peace and to reduce the commerce in arms” (Klare, n.d.).

Hence in his first year in office Carter engineered and authorised PD13. The goal of PD13 was to limit arms sales abroad through “establishing [a] policy of restraint” (PD13, 1977) in regards to arms sales. This policy introduced new caps on the value of arms sales and consequently ensured that a lower value of items could be sold to a non-NATO member states. This document was designed to stop authoritarian and aggressive regimes such as the Shah’s Iran from acquiring and introducing new U.S. developed weapons systems in a specific region. As point 2b of PD13 states, “The United States will not be the first supplier to introduce into a region an advanced weapon system” (PD13, 1977). This was designed with these types of regimes in mind, to attempt to curb the lust and excessive amounts of arms client states such as Iran were purchasing. In addition to this, the US sold $55 billion worth of ammunition alone between the 1971-1977 periods, which was three times the aggregate sales in the preceding two decades (Klare, 2006). Carter, therefore, saw the utility in putting an end to this incremental trend as part of his administration’s wider goal of moving past containment and reducing the global arms race.

After terming PD-13 a “policy of arms restraint” and imposed an aggregate dollar value limit on arms transfers with few exceptions (Kaufman, 2008). In Carter’s first interview as the US president, he reported that the National Security Council had accepted that it was necessary to implement “very tight restrictions on future commitments” to send arms to foreign recipients (Klare, n.d.). However, this was not to be the case as his time in office showed, as path entrenched secret policies of arming proxy nations had been set in place by former president Richard Nixon. Nixon designed the blank check policy, where the Shah of Iran could buy as many weapons as he desired from the U.S. with the exception of WMDs. Nixon designed this partly as a response to the British announcement in 1968 that they would make a military withdrawal from their former colonial territories in the Gulf, upgrading Iranian power to fill the vacuum left by the British. “While a path regarding U.S., arms flowing into Iran was already in place by the end of the 1960s, the significant developments that impacted upon the Carter administration were set into motion by Richard Nixon in May 1972. In a meeting with the Shah in Tehran, Nixon agreed to unlimited and unmoderated arms sales with Iran – with the exception of nuclear weapons technology – in return for the understanding that Iran would use its newfound might to protect the Gulf by proxy (Alvandi, 2012).

This resulted in Carter’s arms restraint policy facing intense pressure from the US and global forces to remove the arms restraint policy. Brzezinski detailed in his book, The Grand Chessboard, that the biggest zone of percolating violence in the world at this point in time was centred in the middle east. Iran holds centre piece in this zone which extends as far as up into Russia and down into Sudan. Brzezinski uses this to argue by default at time of the Carter administration Iran must be kept an ally that was able to protect itself and therefore offshore US interests. This provides wider context as to why Nixon offered the Shah the Blank Cheque deal, leaving Carter with a policy of arming Iran. Carter had to face this intense path dependent foreign policy as well as facing domestic pressure. The pro-Israel groups pushed for its exemption from the PD13 policy and the reinstatement of uninhibited high-technology weapons transfers. The US arms industry also advocated against the restrictive PD13, which limited their profits. Overseas, the Soviets undermined Carter’s resolve to comply with the self-imposed restraint by imposing itself on Third World nations particularly Afghanistan. Ultimately, in 1979 Carter was forced to cave into the mounting antagonism and lift the arms ceiling. This final resolution was a culmination of isolated decisions to permit arms sales that contravened the PD13. Note that PD13 had not done much in the way of halting arms sales, for instance, the total arm sales to Iran alone in 1977 (Carter’s first year in office) was “$5.7 billion” approximately “four times the 1976 total” (McGlinchey, 2014, p141). This demonstrates the path dependent policy of arming the Shah and the power it held over Carter’s arms policies.

The inadvertent failure of PD13, a policy that certainly seemed appealing theoretically is a good illustration of how most of Carter’s liberal ideals fell apart when put to practice. Unlike his human rights policy where let go of his moralist leanings from one case to the other, Carter remained adamant in perpetuating the arms ceiling. PD13 persisted in spite of geopolitical events that threatened US strategic interests elsewhere that occasionally forced the president into making concessions and exceptions. The pursuit of arms reductions across the globe was certainly noble, but its execution during Carter’s regime was nothing but an outcome of misreading the geopolitical landscape.

As the curtain fell on Carter’s administration, the arms policy he had alluded to and so energetically pursued in the early period of his administration had failed. The is best capsulated through the fact that Carter’s first year in office was the highest annual arms sales to Iran on record. This ultimately made way for Carter’s successor president Ronald Reagan who took office in 1981 to effectively retracted what little survived of the previous administration’s arms policy.

The AWACS Sale

The Airborne Warning and Control System (AWACS) were a large and very controversial aspect of the above-mentioned record-breaking year for U.S. arms sales to Iran. The sale of the state of the art developed AWACS was something Carter strongly opposed when he entered office. The sale of this new arms technology would directly contradict PD13, which asserts that “The United States will not be the first supplier to introduce into a region an advanced weapon system” (PD13, 1977). The AWACS were just this as they were by far the most advanced early warning system available, years ahead of any competitor.

Just five days after Carter’s inauguration, the Iranian Ambassador to the U.S. Ardeshir Zahedi visited Brzezinski. At this meeting, Zahedi reminded Brzezinski of the Ford administrations agreements to “raise Iran’s military and civilian purchases by anywhere between $15 and $50 billion” (McGlinchey etal, 2017). Even the lower $15 billion-dollar estimate was “comprised of pending arms sales such as the AWACS, multiple fleets of F-16 fighters and lower order military equipment, spares and ammunition” (McGlinchey etal, 2017). This clearly demonstrates that pressure on the Carter administration was present from Iran from the onset of the administration.

To further add pressure on Carter, Capitol Hill was pressing Carter to limit the amount of weapons sold to the Middle East region. “In a thinly veiled reference to Iran, Senator Frank Church noted that arms sales to Middle Eastern nations had run out of proportion” (McGlinchey etal, 2017). Vance added pressure claiming, “we will sink the peninsula if we keep selling arms”. (McGlinchey etal, 2017). As a result of Carter ’s campaign platform and formulation of PD13, which stated, “Arms transfers are an exceptional foreign policy implement” (PD13, 1977). It is clear why Congress would have expected Carter to limit arms sales, to limit the amount of sensitive technology that could be intercepted by the Soviets or used against the US. This shows that pressure was building from Congress, creating cross-sectioned pressure, both domestically and systemically.

However, Carter went against this pressure and sold Iran, “five AWACS” despite U.S. arms sales being on “hold for the first half of 1977” (McGlinchey etal, 2017). This move was designed to keep the Shah on side whilst only providing him with half the amount he wished to buy. It was also a bid to satisfy Carter’s domestic government that he was attempting to restrict the volume of arms sold abroad. However, the underpinning reason Carter sold these initial AWACS to Iran was that he wanted to be seen as honouring America’s word to its allies abroad. Fearing that if he did not then nations would lose faith in the U.S. and potentially turn to the Soviets. This pivot would be very costly for US geopolitical interests that spanned the globe. Already in the first year of Carter’s term his arms control policy was showing vulnerability to stand the four-year test, demonstrated through this early short coming.

The issue of the full sales of the AWACS and the continuing and growing arms relationship with Iran came to a head in a series of congressional hearings. The overall conclusion within the Carter White House was that this was the biggest government opposition to date over an arms sale. This is best capsulated through Senator Culver, who had extensive knowledge of the AWACS. In Culver’s own words, “we are trying to reverse a very dangerous policy of five years ago, which has got a momentum and a life all of its own, but we have got to draw the line” (Culver, 1977). This was the crunching point at which Cold War containment policy of outsourcing for geopolitical gain was faced with Carter’s liberal agenda, which stated arms sales were to be restricted. However, Carter decided not to withdraw the sale, demonstrating the sheer intensity of Cold War geopolitical strategic demands had over Carter who held genuine intent to halt the arms relationship with Iran. The fact that this happened during Carter’s first year in office is evidence that his arms control and restriction agenda had failed and that this would not be reversible during his tenure in office.

After Carter had left office he recorded and justified the sale of the AWACS on the basis that he did not want to break pre-existing deals, “I was attempting to reduce the sale of offensive weapons throughout the world, but it was not possible to make excessively abrupt changes in current practices, because of the contracts already in existence” (Carter, 1995). However, there is strong doubt that this was the reason at the time of the decision as examined above. Also, contradicting Carter’s overhaul of U.S. foreign policy.

Nuclear Nonproliferation

Carter had the intention of seeking further military as well as paramilitary expansions. Carter, however, was disinclined to the building of the B-I bomber. Kaufman states that Carter’s non-proliferation stance proved consistent with his advancement of human rights as a major foreign policy theme, as the diffusion of atomic technology threatened life and siphoned funding away from essential domestic social programs (Kaufman, 2008, p. 14-15). Even so, the administration’s policy and approaches to key global concerns such as arms control and nuclear non-proliferation posed a threat to trilateral consensus (Ahlberg, 2015, p. 303). In each case, peculiar circumstances with regards to American politics, personality differences as well as a mix of other elements placed the country at odds with its trilateral allies (Ahlberg, 2015, p. 303). Like most of Carter’s foreign policy propositions, trilateral consultation was quite effective in theory particularly at the onset of the administration. However, in practice the administration found itself entrapped in inescapable criticism of pursuing policies that were inimical to strategic interests.

The first snag that the administration hit was during the pursuit of nuclear nonproliferation, which became an immediate testing episode of the trilateral relations that Carter envisioned. In his presidential campaign, Carter revealed the approach he would apply to non-proliferation (Ahlberg, 2015, p. 303). His intention was to reduce the amount of plutonium and uranium, pursue the amelioration of global safeguards, and advocate for delays in commercialising nuclear technologies (Ahlberg, 2015, p. 303). By linking nuclear exports to non-proliferation, the president made it possible to fuse American nuclear program with his aspiration to reduce the proliferation of weapons throughout the globe (Martinez, 2002, p. 265). When Carter entered office, he immediately sought to pursue these goals domestically and declared reforms in April 1977. In short, the new US policy detailed seven initiatives in non-proliferation such as the postponement of plutonium reprocessing, an embargo on the export of uranium enrichment equipment (Ahlberg, (2015, 304). Carter’s approach defied the precedent set by previous administrations. As Martinez (2002, p. 269) notes,

“Through a principled, high-profiled, politicised stance that cast aspersions on any nations that contributed to proliferation, the United States moved away from its previous efforts at building an international coalition.”

The move threatened alliances because key US allies already had arrangements in place that contravened the policy. For instance, Germany and Brazil had a 1975 agreement that permitted nuclear technology imports into Brazil and was set to begin following Germany’s 1977 license grants to Brazil (Ahlberg, 2015, p. 304). Even though the arrangement opposed Carter’s policy, West German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt justified the intended sale stating that it was for peaceful purposes and, therefore, within the transfers permitted by the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (Kaufman, 2008).

Most European leaders were not pleased the Carter’s “new departures of nuclear nonproliferation” and it “evoked strong protests against American unilateralism” (Brzezinski, 1982, p. 292). U.S. relations with the Federal Republic of Germany and Brazil became strained. At the time, the U.S. had abundant uranium coupled with significant non-nuclear energy sources became prone to “the charge of being the dog in the manger-denying to others something which it did not need itself” (Smith, 1986, p. 61).

Another controversy ensued that threatened trilateral cooperation with regards to the administration’s stand on enhanced radiation weapon also referred to as the neutron bomb (Ahlberg, 2015, p. 306). This situation plunged Carter in a bind where if he did not authorise the weapon, the US military and Congressional members would be angered (Kaufman, 2008, p. 50). Cancelling the Enhanced Radiation Weapon (ERW) production on the heels of his denial of the B-1 bomber would make him seem weak in the eyes of his critics (Kaufman, 2008, p. 50). Alternatively, proceeding with the production would anger policymakers as well as Americans who deemed nuclear weapons immoral and a direct violation of his principle to advance human rights (Kaufman, 2008, p. 50). Also, it would amount to a contradiction of his call for disarmament (Kaufman, 2008, p. 50). Rather than make his decision immediately, Carter chose to stall and directed the Department of Defence (DOD) to submit a comprehensive report detailing the utility of the weapon or otherwise.

Eventually, the Department of Defence issued its report in favour of the production of ERW as a key component of a wider modernisation tactic and to act as a deterrent against the USSR (Ahlberg, 2015, p. 306). An idealist at heart, Carter was not desirous of the production of the new warhead, let alone their deployment and wished to be far-removed from the production of the ERW (Strong, 2000, p. 133). Carter, consequently, found another dilatory tactic by making his approval for the creation of the ERW contingent upon the open agreement of European leaders regarding its deployment or he would terminate the initiative altogether (Ahlberg, 2015, p. 306). As fate would have it, European dissent of ERW intensified throughout 1977 (Ahlberg, 2015, p. 306). On their part, North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) members privately supported the weapon and expected that the president would kick off the production, and leave the issue of deployment to be determined at a later date (Ahlberg, 2015, p. 306).

In the end, Carter decided not to produce the neutron weapon. The leader later justified his decision by articulating that it was “not only logical on its own merits and compatible with the desires of most of our European allies, but it also conformed to our general policy of restricting nuclear weaponry” (Carter, 1982, p. 220). Even so, his “double message” regarding ERW needlessly complicated American relations that were already fractured to some extent by the administration’s shaky policy on human rights (Kaufman, 2008, p. 51). Even though the outcome was pleasing to European allies, the entire episode surrounding neutron weapons damaged Alliance relations. However, Carter managed to demonstrate a strong commitment to trilateralism when he heeded Europe’s concerns, demonstrating that the US would treat key economic and military allies in an equal fashion (Strong, 2000).

Carter’s Approach to SALT Accord with the Soviets

The most pertinent arms-related policy with Russia concerned the Strategic Arms Limitations Treaty, also popularly referred to as SALT. Rather than leverage the rapport that Moscow’s Leonid Brezhnev and his immediate predecessor President Ford had established, Carter took a parallel route. Carter developed SALT II as Carter felt SALT allowed for the U.S. and USSR to pick and choose what option to follow which did not make a complete arms trade treaty. The SALT II treaty however, in Carter’s words, “For the first time, it places equal ceilings on the strategic arsenals of both sides” (Carter, 1979). This was done as it established numerical equality between the two nations in terms of nuclear weapons delivery systems and MIRV missiles. As well as tackling newer arms technologies such as strategic nuclear weapons that were being developed. However, this never happened as the U.S. refused to ratify the treaty when a Soviet brigade was located off the Cuban coast by the U.S. The U.S. believed this was recently positioned by the USSR. Later after the USSR invaded Afghanistan, any hope for U.S. ratification was abandoned.

Carter’s naval experience made him fear the destructive power of existing nuclear weapons, and he desired that his efforts in formulating SALT II would put a stop to the dissemination of nuclear weapons to other nations. He also hoped to check the relentless arms race that characterised the geopolitical landscape. In a speech in 1979 he called for peace between the U.S. and USSR, “The truth of the nuclear age is that the United States and the Soviet Union must live in peace” (Carter, 1979). The central issue of Carter pushing a more liberal agenda via SALT II is that when it was met with Soviet hard line realpolitik approach it could not stand its ground or adjust accordingly. Emphasising the issues of idealistic policy in the Cold War.

Carter adjusted to this as his administration began following the recommendations of Congressman Joe Wilson and CIA agents. As a result, they furnished Mujahideen guerrillas with heavier weaponry to fight the USSR-backed government through operation Cyclone. By mid-1979, the United States had started a “covert program to finance the Mujahideen” (Meher, 2003). Showing that the Carter administration opted to preserve geopolitical interest opposed to continuing his liberal agenda. Once again demonstrating that carter did not only have to bend his liberal agenda in the Cold War era, but was forced to board the realist train that formulated US foreign policy in the administrations before and after. The Carter administration went a step further attempting to provoke the Soviets into further war. Brzezinski was later quoted as saying that the goal of the program was too “induce a Soviet military intervention” (Gibbs, 2000). This startling revelation from the Carter administration emphases the about turn from a human rights agenda to a realpolitik stance, looking to protect geopolitical interest in the Middle East, mainly Iran which neighbours Afghanistan.

Donald S. Spencer on the Carter’s administrations arms policies and behaviour

Donald Spencer is Associate Dean of the Graduate School and Associate Professor of History at the University of Montana. Spencer offers an academic insight that fuses a critique of Carter’s arms policies with the context of the Cold War realpolitik period. Spencer noted that due to the final year of Carter’s tenure, “his campaign promises had disintegrated into the spectacle of a great nation in confused and global retreat” (Spencer, 1988, p. ix). In summary, Carter’s foreign policy on arms failed. The main reason for this is that the president focused on implementing idealistic policies that were parallel to the prevailing context of his leadership as he was keen on moving the world past traditional realpolitik containment. Consequently, the Carter administration took steps that threatened its alliances as well as its national security.

Carter’s double-mindedness kept his supporters, critics, and strategic national allies guessing at all times, to the extent that it almost fractured trilateral cooperation. The president-engulfed stakeholders in great suspense over the ERW production that he later declined on the basis that he could not enlist European support for its deployment. In the meantime, NATO read accurately into the USSR’s moves as well as the prevailing geopolitical environment accurately and supported the production. Spencer’s (1988, p. ix) statement that the “administration lacked any sophisticated understanding of how nations behave” is highly befitting of Carter’s tenure. He seemed overly persuaded by the progress made in SALT II and failed to read into the actions of the Soviets globally. As the curtain fell on his tenure, SALT II debates had been put on hold to the extent that he could not openly lobby for its ratification. In the meantime, nuclear proliferation gained new appeal effectively reversing the administration’s nonproliferation efforts.

Perhaps the only area where Carter stood his ground, albeit speciously was with regards to the arms ceiling. The president perpetuated PD13, another highly-romanticised theory that stemmed from his liberal leanings. Carter felt that it was timely to pursue widespread disarmament to ensure global peace, but his timing limited this. Implementing PD13 was problematic as its basis ignored the realist setting foreign policy was being formulated in. Administrations across the world needed access to arms due to prevailing instability including Afghanistan. The outcome was the removal of a US-friendly president and subsequent installation of a pro-Soviet leader. The best indication of the failure of PD-13 is that the president abandoned it altogether as his regime ended. At the vantage point of four decades after Carter’s tenure, the abandonment of PD13 verifies all criticisms that Carter failed to heed that his policies were unrealistic given the prevailing circumstances.

Conclusion

Carter’s proposed foreign policy to revolutionise it from a foundation of strategic realpolitik basis to a liberal based policy of arms restraint and human rights was a failure. Carter held a genuine liberal ideology but lived in a realist era, perhaps if his tenure had fallen during the 1990s post Cold War era his foreign policy record would have been different. Due to Carter’s nature, this led to him attempting to appease both sides both systemically and domestically by micromanaging every issue, ultimately leading to his administration having one foot in liberalism and one foot in realism. Carter’s presence was an idealist hub surrounded by a White House engrained in hardline realpolitik policy making.

With regards to his human rights policy, Carter achieved notable successes in promoting human rights in Latin America, except Nicaragua. However, rather than build on these achievements, he took an entirely different posture toward Iran, China and South East Asia, which were far more strategically important frontiers of the Cold War. Once a sharp critic of authoritarianism, Carter got entangled in plying the interests of dictators, even in instances where he had the opportunity to raise human rights concerns such as Iran. The implication of this disparate application of his original intention was the success registered in certain parts of Latin America along with the perpetuation of human rights violations by dictators in China, the Philippines, Indonesia, and Iran. What the president ended up accomplishing in this area was a far cry from his ‘absolute’ commitment to advancing human rights by infusing humanitarian concerns into American foreign policy. Rather the support for the aforementioned regimes resulted in the Carter administration funding the oppressing of civilians.

Carter’s liberal principles regarding arms also failed to stand the test of a single term as president. This came as his administration’s policies ignored the prevailing geopolitical landscape and attempted to include moral change where it was not possible. His administration misread and underplayed developments in the global scene that served as an indicator that idealist standpoints would be impractical. As a result, the administration expended its efforts on arms policies that failed completely even before the end of Carter’s tenure. Most of what would have been the president’s signature policies on arms were unsuccessful including SALT II, PD13, attempting to halt the AWACS sale and nuclear non-proliferation. The implementation of these miscalculated and mismanaged measures strained trilateral relations greatly and put the country and its strategic foreign policy at risk in light of incremental Soviet assertiveness overseas. In his memoirs, Carter defends his idealist leanings with regards to arms as moral as well as practical. While morality that informed Carter’s decisions is indisputable, the preceding argument demonstrates that the feasibility of his policies did not match the period his presidency spanned and failed due to the hardline realpolitik White House they were trapped in and the politically fierce world they were applied to.

References

Ahlberg, K. (2015). Trilateralism in A Companion to Gerald R. Ford and Jimmy Carter, ed. Scott Kaufman. New York: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 290-311.

Alvandi R, ‘Nixon, Kissinger, and the Shah: The Origins of Iranian Primacy in the Persian Gulf’, Diplomatic History, 36: 2 (2012); and Stephen McGlinchey, ‘Richard Nixon’s Road to Tehran: The Making of the U.S.-Iran Arms Agreement of May 1972’, Diplomatic History, 37:4 (2013).

Beinart, P. (2006). The rehabilitation of the Cold-War liberal. The New York Times Magazine [online] 30 April. Available at <http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/30/magazine/the-rehabilitation-of-the-coldwar-liberal.html> [Accessed 25 Feb. 2017].

Brzezinski, Z. (1982). Power and Principle: Memoirs of the National Security Adviser, 1977-1981. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux.

Carter, J. (1977). Inaugural address. UCSB [online] n.d. Available at: <http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=6575> [Accessed 1 Mar. 2017].

Carter, J. (1978) Speech on Establishing Diplomatic Relations with China. [online]. The Miller Centre for Public Affairs. Available from: https://millercenter.org/the-presidency/presidential-speeches/december-15-1978-speech-establishing-diplomatic-relations [Accessed 08 April 2017].

Carter, J. (1979). Speech on SALT II. The White House. Available from: http://www.cvce.eu/content/publication/1999/1/1/6f1ced84-c4ee-42ba-a57b-41013c49a4a4/publishable_en.pdf [accessed 07.03.2017]

Carter, J. (1982). Keeping Faith: Memoirs of a President. New York: Bantam Books. p123, p240

Clymer, K. (2003). Jimmy Carter, Human Rights, and Cambodia. Diplomatic History, 27 (2) pp. 245-278.

Statement by Senator Culver, (1977). ‘Hearings before the subcommittee on Foreign Assistance and the committee on Foreign Relations on Proposed Sale of Seven E-3 Airborne Warning Control System Aircraft to Iran: July 18, 22, 25, 27 and September 19, 1977’, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington D.C. 1977.

Dobson, A. and Marsh, S. (2006). US Foreign Policy since 1945. 2nd ed. Oxford: Routledge.

Dreyfuss, R. (2005). Devil’s Game: How the United States Helped Unleash Fundamentalist Islam. New York: Holt Paperbacks.

Gibbs, D.N. (2000) Afghanistan: The Soviet Invasion in Retrospect [online] Available from: http://dgibbs.faculty.arizona.edu/sites/dgibbs.faculty.arizona.edu/files/afghan-ip.pdf [Accessed 7th April 2017].

Gasiorowski, M (2013) The CIA’s TPBEDAMN Operation and the 1953 Coup in Iran. Journal of Cold War Studies, Fall 2013, Vol. 15, No. 4 [online] Available from: http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1162/JCWS_a_00393#.WPrhWVPyuis [Accessed 10th April 2017].

Jones, B. W. (2015). 1979 Year of Crises in A Companion to Gerald R. Ford and Jimmy Carter, ed. Scott Kaufman. New York: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 410-429.

Kaufman, B. I., ad Kaufman, S. (2006). The presidency of James Earl Carter Jr. (2nd ed., rev.). Laurence: University Press of Kansas.

Kaufman, S. (2008). Plans Unraveled: The Foreign Policy of the Carter Administration. De Kalb: Northern Illinois University Press.

Klare, M. No Date. Carter’s arms policy. NACLA [online] n.d. Available at: <https://nacla.org/article/carters-arms-policy> [Accessed 1 Mar. 2017].

Martinez, M. (2002). The Carter administration and the evolution of American nuclear nonproliferation policy. Journal of Policy History 14, 261-292.

Meher, J. (2003) America’s Afghanistan war: The success that failed Kalpaz Publications. pp 68 – 69

Metzl, J.F., (2016). Western Responses to Human Rights Abuses in Cambodia, 1975–80. Springer

McGlinchey, S. (2014). US Arms Policies towards the Shah’s Iran London: Routledge.

McGlinchey, S & Murray, R (2017). Accepted version: Forthcoming in Diplomacy and Statecraft, August 2017

Mousavian, S. & Shahidsaless, S (2015). Iran and the United States. New York: Bloomsbury.

Murray, D. (2010). US Foreign Policy and Iran. London: Routledge.

Nazemroaya, M (2007) America’s “Long War”: The Legacy of the Iraq-Iran and Soviet-Afghan Wars. [online] Available from: http://www.payvand.com/news/07/sep/1186.html [accessed 1st April 2017]

Office of the Historian, Bureau of Public Affairs US Department of State. No date. 1977-1981: The presidency of Jimmy Carter. Office of the Historian [online] No date. Available at: <https://history.state.gov/milestones/1977-1980/foreword> [Accessed 13 March 2017].

Offiler, B. (2015) US foreign policy and the modernization of Iran: Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon and the shah (security, conflict and cooperation in the contemporary world) [online]. Palgrave Macmillan

Olson-Raymer, G. No date. The 1970s and the 1980s: The decline of liberalism and the triumph of conservatism. Humboldt State University [online] n.d. Available at <http://users.humboldt.edu/ogayle/hist111/1970sand1980s.html> 1 Mar. 2017.

The White House. Jimmy Carter (1979) Presidential Directive/NSC 13. Washington DC. Available from: https://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov/documents/pddirectives/pd13.pdf

Pollack, K. (2004). The Persian Puzzle. New York: Random House.

Renouard, J. (2015). Get Carter: Assessing the Record of the Thirty-Ninth in A Companion to Gerald R. Ford and Jimmy Carter, ed. Scott Kaufman. New York: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 491-512.

Ribuffo, L. P. (2015). Jimmy Carter, Congress, and the Supreme Court in A Companion to Gerald R. Ford and Jimmy Carter, ed. Scott Kaufman. New York: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 379-409.

Seliktar, O. (2000). Failing the Crystal Ball Test. Boulder, CO: Greenwood Publishing Group.

Simpson, B. (2009). Denying the ‘First Right’: The United States, Indonesia, and the Ranking of Human Rights by the Carter Administration 1976-80. International History Review, 31 (4) pp. 798-826.

Smith, G. (1986). Morality, Reason, and Power: American Diplomacy in the Carter Years. New York: Hill and Wang.

Snyder, S. (2016). Human rights and US foreign policy. Oxford Research Encyclopedias [online] May. Available from: <http://americanhistory.oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.001.0001/acrefore-9780199329175-e-267?print=pdf> [Accessed 3 February 2017].

Spencer, D. S. (1988). The Carter Implosion: Jimmy Carter and the Amateur Style of Diplomacy. New York: Praeger.

Strong, R. A. (2000). Disarming Diplomat: The Memoirs of Gerard Smith, Arms Control Negotiator. Lanham, MD: Madison Books.

Trenta, L. (2013). The Champion of Human Rights Meets the King of Kings: Jimmy Carter, the Shah and Iranian Illusions and Rage. Diplomacy and Statecraft [online] n.d. Available at: http://goo.gl/mGe3HV [Accessed 12 January 2017].

Willis, E. (2014). Jimmy Carter’s Human Rights Policy: The Rhetoric and Reality in Cambodia and China. University of Georgia [online] 26th March. Available from <http://digitalcommons.northgeorgia.edu/ngresearchconf/2014/PSIACrjuHist/5/> [Accessed 27 Feb. 2017].

Written by: David Buckland

Written for: Dr Stephen McGlinchey

Written at: UWE Bristol

Date Written: May 2018

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Puzzle of U.S. Foreign Policy Revision Regarding Iran’s Nuclear Program

- ‘Almost Perfect’: The Bureaucratic Politics Model and U.S. Foreign Policy

- Israel’s Qualitative Military Edge: U.S. Arms Transfer Policy

- The Carter Administration and Human Rights in Chile, 1977-81

- “Sanctions Are Coming”: Fear and Iranophobia in American Foreign Policy

- How National Identity Influences US Foreign Policy