Much of the news in the west about Iran at present concerns the stand-off between Washington and Tehran. The US has imposed sanctions on Iran after the US withdrew from the 2015 nuclear deal. Hopefully both sides will continue to hold back from the horror of another war in the Middle East. At the same time but less reported was other news in the UK relating to Iran. For two weeks in June, a lone brave figure, Richard Ratcliffe, camped outside the Iranian Embassy in London on a hunger strike. Ratcliffe was protesting the Iranian authorities continued refusal to release his wife, Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, from Evin prison where she is serving a sentence on vague spying charges. At the same time, Nazanin underwent her own hunger strike. In June, Iran had once again refused to release Nazanin, despite a Foreign Office official personally delivering a request for her release. I visited the embassy on an evening in June when Amnesty International had organised a sing-along with Richard and his supporters.

Although neither Ratcliffe nor his wife had any connection with this, his act fell on the 10th anniversary of the Green Movement in Iran, when, two years before the Arab Spring, thousands of Iranians poured onto the streets demanding civil liberties. The Green movement began as a mass demonstration against the declared electoral victory of Mahmoud Ahmandinejad, which was a result many believed to have been rigged. Their slogan initially was “where is my vote?” In 2009, in Iran and also outside the Iranian Embassy in London, when I joined, there were mass demonstrations and civil disobedience. These lasted until the following year when the protesters’ attempt to stage a rally in support of the Arab Spring was suppressed. The nominal leaders of the movement were arrested and jailed.

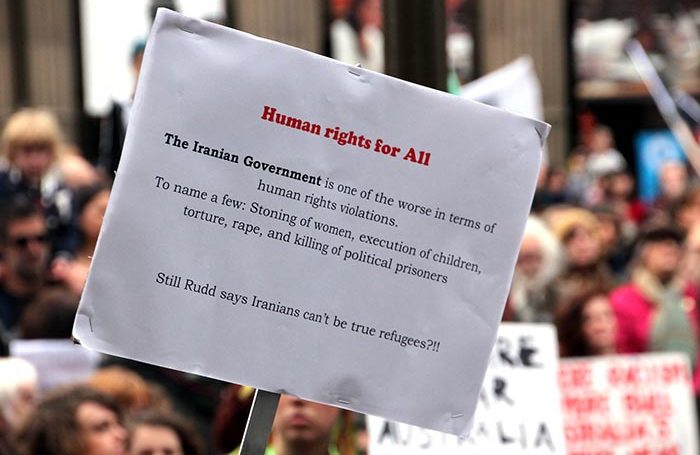

Richard Ratcliffe’s brave act was relatively unfamiliar in the UK, but it is a measure Iranians have been forced to resort to before. In the context of extreme punishments being meted out for what Iran’s leaders consider ‘crimes,’ such as women removing their hijabs in public or lawyers doing their jobs. Recently, Nasrin Sotoudeh was sentenced to 38 years and 148 lashes for defending human rights. This was the second of two verdicts against Nasrin. The ‘charges’ included ‘gathering and collusion against national security,’ and ‘encouraging people to corruption and prostitution.’ Her own account of her ‘crime’ was that she defended the ‘Girls of Revolution Street;’ who took part in protests against the compulsory wearing of the hijab in the wake of the widespread uprisings in 2017. These uprisings were partly about the dire economic situation – starting unusually in Mashhad, Iran’s second city, but they also focused on political repression in the country. Protests spread in 2017 and 2018 to 50 cities and towns.

Recently, British musician Joss Stone posted on Instagram, while wearing a white headscarf captioned: “Well, we got to Iran, we got detained and then we got deported.” She said she knew solo performances by women were illegal. Refusing to allow women musicians to perform alone in public is commonplace in Iran. In 2018, Sepideh Jandaghi, an Iranian musician, who produces traditional music, reported that she was only allowed to sing if she performed with a man, which she had not wanted to.

In a setting where ordinary people can be arrested and imprisoned for defending the rights of individuals to engage in a small protest (such as removing hijabs in public), brave people, now including Richard Ratcliffe, are forced to engage in extreme measures to draw attention to these crimes from public figures and ordinary people in the West. According to Amnesty International, 7000 people were arrested in 2018. These included students, lawyers, teachers, women’s rights activists and trade unionists. Hundreds were sentenced to prison or flogging and several prisoners died while in custody. An image of a women removing her white headscarf became symbolic for the protesters in 2017 and 2018. No doubt, some who were arrested, like Zahari-Ratcliffe, had done nothing to gain the attention of the government.

All this happened in a country where the principle of ‘velayat al faqih’ is in operation. The constitution of Iran, which is an Islamic Republic, outlines a state ruled by Islamic jurists (Fuqaha). In accordance with verse 21/105 of the Koran and on the basis of two principles of trusteeship it gives to the Supreme Leader very strong powers, including the power to appoint and dismiss judicial authorities. Iran is a prime example of a state which practices a fundamentalist form of Islam. Fundamentalist, or political Islam is antidemocratic and absolutist.[1] The Islamic Sharia, or code of conduct, while avowedly subject to wide interpretation, is opposed to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, democratic governance, religious tolerance, ethnic diversity and political pluralism.[2] Minorities under Islamic rule enjoy protection at best, not equal status. Since Islam is a polity ruled by Allah, disobedience toward Allah’s surrogate rulers is seen as not only a sin but a crime against the state, leaving no room for criticism, disagreement or dissent.

Fundamentalist forms of Islam are but one form of religious fundamentalism. Fundamentalist forms of many religions, including Islam, but also Hinduism, Buddhism and Christianity are rising across the world. At the same time, racism against minority groups and against minority religions, in any given nation, is also rising. In Iran, Christians are a minority group and can be imprisoned for practicing their religion. A 2018 report notes that a Christian in Iran was charged with “acting against national security through the formation and establishment of an illegal church organisation in his home.” He was sentenced to 10 years in Even Prison. His crime was setting up a prayer group in his home. International Christian Concern (ICC), an anti-persecution charity, claims that he is facing “completely losing his teeth” due to lack of medical treatment.’

In the UK, racism against Muslims, a minority group in this country, is increasing at the same time as radicalisation of young people in support of fundamentalist forms of Islam. The introduction of the recent issue of Feminist Dissent states: ‘[R]adicalisation (of young people in the UK context becoming sympathetic to fundamentalist forms of religion) is a real and serious issue.’ As noted in Feminist Dissent, the British state is entirely capable of racist abuses of human rights. However, it is important to reject the simplistic narrative of opposition between a repressive surveillance state on the one hand and a demonised, misrepresented and monolithic community on the other. This binary construction of power closes down discussion of resurgent religious fundamentalism, particularly Muslim fundamentalism, the risks these ideologies pose and the harms they cause. The case of Iran, outlined above, should give us in the West pause for thought. Iran and the USA may be at loggerheads, but we should be wary of valorising one or the other. The notion of a human right, enshrined in the UN Convention, whilst it may be an imperfect tool for the defence of all of us, is nonetheless vital in the context of the rise of the far right, on the one hand, and religious fundamentalism on the other.

Notes

[1] Judith Miller, “The Islamic Wave,” The New York Times Magazine, May 31, 1992

[2] Martin Kramer, “Islam vs. Democracy,” Commentary, January 1993

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- National Honor and Religious Duty: Iran’s Strategic Evolution in Confronting Israel

- Opinion – Human Rights Concerns as Somaliland Seeks International Recognition

- Engaging Iran

- Human Rights Movements in the Middle East

- Opinion – Narges Mohammadi’s Nobel Peace Prize and Iran’s Historic Clash

- Opinion – The Path Beyond Trump in US Human Rights Policies