This is an excerpt from The United Nations: Friend or Foe of Self-Determination? Get your free copy here.

The year 2018 marks the 70th anniversary of the First Indo-Pakistani War over Jammu and Kashmir (simplified as Kashmir from hereon in) and United Nations (UN) Security Council Resolution 47. This resolution stipulated that both India and Pakistan should withdraw their military forces and arrange for a plebiscite to be held in order to provide the people of Kashmir the choice of which state to join (S/RES/47) Ostensibly this resolution was an effort by the UN Security Council to put the right to self-determination into practice. Yet I argue that a closer inspection reveals that the Security Council, by limiting the choice for the people of Kashmir to accession into either India or Pakistan, and its lackadaisical efforts to implement the plebiscite the resolution called for, was in fact privileging another norm: the existing sovereign state’s rights. The basis for this decision is at the heart of the UN Charter itself. Although the UN Charter famously calls for the ‘equal rights and self-determination of peoples’ in Article 1, Article 2 also clearly states ‘nothing contained in the present [UN] Charter shall authorise the UN to intervene in matters that are essentially within the jurisdiction of any state’ (1945, 3). As the peoples seeking self-determination are inherently within a state, the norm of self-determination typically finds itself in conflict with the norm of state territorial integrity. The situation becomes further confused when the people in question occupy a territory that is contested between two sovereign states, as is the case in Kashmir.

The Kashmir situation is far from unique. Though few other self-determination movements exist within territory actively disputed between two states, the UN has been consistently reluctant to recognise any self-determination movements seeking to break from already recognised states. This remains the case whether the movements have already established a de facto state, such as Somaliland and Transnistria, or are aspirant independence movements, such as those undertaken by the Tibetans, Kurds or West Papuans. This chapter is dedicated to illuminating the tension that exists between the principle of self-determination and the rights of state sovereignty that is inherent within the UN. In using the case of Jammu and Kashmir, one of the earliest incidences where this normative clash occurred, this chapter demonstrates that while the UN formerly advocates for self-determination, it in practice upholds the principle of territorial sovereignty. However, before we can explore the history and ramifications of the UN Security Council’s actions concerning Kashmir, we must first define these terms, explore why they are often in conflict with each other and how the UN has sought to employ them.

Self-Determination, Sovereign Territorial Integrity and the UN

One significant source of tension that exists within the theory and practice of international law is between the principle of self-determination and the norm of state sovereignty, especially when it concerns the state’s territorial integrity. Broadly defined, self-determination is the philosophical and political principle that people should have the right to shape their own political, economic and/or cultural destiny. In contrast, the norm of sovereignty refers to the claim of a state, recognised by other states, to be the exclusive political authority within a specific territory. Whilst self-determination is often the foundation for a state, it becomes an issue when an aspirant people seek to separate from an established state, either attempting to establish their own separate state (secessionism) or to join another state (irredentism) (Taras and Ganguly 2006, 41–44). The norm of state sovereignty has two primary components.

The first is the principle of non-interference, or the expectation that states should be free to conduct their internal affairs without any outside interference. The second is the principle of territorial integrity, or that a state’s borders are sacrosanct and thereby should not be altered without the consent of all relevant parties. In other words, the territorial integrity aspect of the norm does not recognise the right of people to engage in a unilateral secession, whilst the non-interference requirement ensures that international actors cannot legitimately compel the state to do so (Makinda 1998, 103–105). Hence, the principle of self-determination frequently finds itself in conflict with the norm of state sovereignty.

Interestingly, despite the UN’s well-earned reputation for being divided and equivocating upon many issues, it has been surprisingly united and consistent in its favouring the norms of non-interference and the territorial integrity of a sovereign state over the self-determination of peoples. The only example of the UN unequivocally embracing the principle of self-determination was its support movement for decolonisation. This consideration was most clearly articulated in two General Assembly’s declarations. The first of these was Resolution 1514 (XV), more commonly known as the Declaration Granting Independence to Colonial

Territories, Countries and Peoples, proclaimed in December 1960. This declaration decreed that ‘the subjection of peoples to alien subjugation, domination and exploitation… is contrary to the Charter of the United Nations’ and proclaimed that ‘all peoples have the right to self-determination; by virtue of this right they freely determine their political status and to pursue their economic, social and cultural development’ (A/RES/1514 [XV]).

The second declaration was Resolution 2625 (XXV), more commonly known as the Declaration on Principles of International Law, Friendly Relations and Co-operation Among States in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations, proclaimed in October 1970. This declaration explicitly stated that the principle of self-determination’s goal was ‘to bring a speedy end to colonialism, having due regard for the freely expressed will of the peoples concerned’ (A/RES/2625 [XXV]). Furthermore, it specified that ‘the establishment of a sovereign or independent state, the free association or integration with an independent State or the emergence into any other political status freely determined by a people constitute modes of implementing the right of self-determination’ (ibid.).

However, once the process of decolonisation is complete, the focus of the right to self-determination within the UN organs shifts from the people to the state itself. Indeed, the Declaration on Principles of International Law proclaimed:

Nothing in the forgoing paragraphs shall be construed as authorising or encouraging any action which would dismember or impair, totally or in part, the territorial integrity or political unity of sovereign and independent states conducting themselves in compliance with the principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples described above and thus possessed of a government representing the whole people belonging to the territory without distinction as to race, creed or colour (ibid.).

In other words, the General Assembly was asserting that once the process of decolonisation is complete, the state’s sovereign rights to territorial integrity and political autonomy take precedence. The basis of this post-colonial pivot towards the norm of state sovereignty is based upon the principle of uti possidetis. In essence, the principle of uti possidetis stipulates that when a former colony secedes from an empire, the new state’s borders should match its former administrative boundaries (Taras and Ganguly 2006, 45). Any alteration of these borders only occurring after an international agreement involving the new state or with the state’s own consent. Thus, any unilateral efforts by secessionist or irredentist movements to break away from an existing state are not recognised by any UN organs, with such actions only becoming legitimate if the existing state accepts the split (Chandhoke 2008, 2–4).

In part, the adoption of the principle of uti possidetis has been purely pragmatic owing to the difficulty of adequately establishing a territorial state that does not contain some minority within it and the general reluctance for established states to accept being bifurcated. Yet the favouring of the nation-state has also been partly adopted by design, with several scholars arguing that an unstated goal of the UN has been to freeze the political and territorial map after the process of de-colonisation (Saini 2001, 60–65; Taras and Ganguly 2006, 45–46).

By and large, this freezing of territorial boundaries has been a boon for international peace as the late twentieth century saw a marked reduction of interstate wars over territory and for ‘national reunification’. Indeed, most of the international community could agree that the maintenance of colonies was against the principle of self-determination and that as colonies are by definition not part of a state’s core territory, they were hard to justify by appealing to their sovereignty. However, this peace has come at the UN’s sacrifice of a broader application of the principle of self-determination to any aspirant non-self-governing peoples in non-colonial states who see little future within their current borders or otherwise wish to break away. During the UN’s first five years, there were several cases of non-self-governing territories that the General Assembly or Security Council could have sought to apply the principle of self-determination to any aspirant peoples rather than defer to existing state interests.[1] One of the most prominent of these cases was the India-Pakistan conflict over Kashmir.

The Origins of the Jammu and Kashmir Dispute

During British rule, the subcontinent was governed in part through territories that British authorities directly administered and in part through a number of semi-autonomous vassals known as Princely States. One of the largest of these Princely States was Jammu and Kashmir, situated in the northwest corner of British India. The territory came under British suzerainty in 1846 when the British East India Company sold the Valley of Kashmir to the Raja of Jammu, Gulab Singh, and recognised him as a Maharaja in return for his acceptance of British overlordship (Schofield 2000, 7–10). When the British withdrew from the subcontinent in 1947, they partitioned their former colony roughly along sectarian lines to create India and Pakistan in a futile effort to reduce the bloodshed between supporters of the bitterly feuding All India National Congress of Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru and the Muslim League of Muhammad Ali Jinnah. As part of this partition, all the Princely States would be forced to sign the Instruments of Accession which would incorporate their lands into one of the new states. Although the respective ‘princes’ could choose which state their realm would be absorbed into, they were encouraged by the British to consider both their geographical location and the demographics of their subjects (Behera 2006, 5–14).

At the time of the British withdrawal, Kashmir was approximately 77% Muslim and bordering the western wing of Pakistan. This would have theoretically ensured that joining Pakistan would have been a natural choice. However, there also existed several minorities within Kashmir which favoured India, most notably the Buddhist Ladakhis in the north and the Sikhs and Hindu Dogras in the south (Behera 2006, 104–105). Additionally, the Muslim population of Kashmir was not homogeneous, with many following the mystic Sufi tradition of Islam with significant pockets of Shia and orthodox Sunni populations (Snedden 2013, 9–10). A final issue came from the political leanings of the local authorities and personalities of Kashmir. Although there were supporters for acceding to either India and Pakistan, the key Kashmiri political actors at the time were the Hindu Maharajah, Hari Singh, and the leader of the All Jammu and Kashmir National Conference, Sheikh Abdullah.

Singh had ruled Kashmir with increasing despotism since he ascended to the throne in 1925, paying little attention to his ministers or local council when passing laws, imposing discriminatory taxes on Muslims. As a result, Singh was a highly unpopular ruler and often had to use his military, often with the assistance of British forces, to crush local unrest (Schofield 2000, 17–18). Nonetheless, as the Maharajah, Singh was empowered to make the decision whether to accede his kingdom to India or Pakistan. However, Singh personally disliked both Jinnah and Nehru and clearly wished to maintain his control over Kashmir. Thus, Singh deliberately equivocated in declaring for either India or Pakistan, seemingly believing that by delaying the decision he could achieve de facto independence for Kashmir (Subbiah 2004, 175). Abdullah and the All Jammu and Kashmir National Conference represented the main local opposition to Singh. Hence, their primary policy aims were concerned with ending the Maharaja’s rule and establishing a secular representative government in Kashmir. Yet, while Abdullah hated the ideological concept of Pakistan and was good friends with Nehru, his clearly preferred status for Kashmir since 1944 was to establish it as ‘an independent political unit like Switzerland in South Asia’ (Lamb 1991, 187–190; Snedden 2013, 25).

By the end of October 1947, two months after Britain formally withdrew from the subcontinent, both India and Pakistan were growing impatient for Singh to make his accession decision. It was Pakistan, increasingly convinced that India was trying to smother it or at least cheat it out of economic and strategically important territory, that moved first (Hajari 2015, 180–189). In an effort to secure Kashmir for Pakistan, several members of the Pakistani military and government orchestrated an invasion of pro-Pakistan Islamic zealots from the Pashtun tribes on Pakistan’s western frontier. The Maharaja’s forces, already occupied trying to pacify an unrelated anti-Maharaja pro-Pakistan rebellion in the Poonch region, were completely unprepared to resist such an invasion and were swiftly routed. India refused to assist unless Singh signed the Instrument of Accession in favour of India. Thus Singh, recognising that his political position had collapsed and desperate to gain Indian help in repulsing the invasion, formally signed the document in favour of India on 26 October 1947 (Schofield 2000, 41–54).

Despite the obviously coerced nature of Singh’s signature and the fact that it went against the pro-Pakistan or independence aspirations of many Kashmiris, India’s leadership was convinced that Singh’s accession gave India both the legal and moral right to the Princely State. This mentality was buttressed by the fact that India was able to rush in enough troops to halt the advance of Pakistan’s proxy forces upon the Kashmiri capital of Srinagar and even reverse some of their territorial gains. However, India was not able to inject enough troops into Kashmir to advance far before winter made further operations impossible. With the weather ending any further campaigning from either side, Nehru decided to call upon the Security Council to mediate believing the UN would compel Pakistan to withdraw (Subbiah 2004, 176–177). Thus, on 1 January 1948, Nehru wrote a letter to the UN Security Council (S/628), arguing that:

Under Article 35 of the Charter of the United Nations, any member may bring any situation, whose continuance is likely to endanger the maintenance of international peace and security to the attention of the Security Council. Such a situation now exists between India and Pakistan owing to the aid which invaders…are drawing from Pakistan for operations against Jammu and Kashmir, a State which acceded to the Dominion of India…The Government of India requests the Security Council to call upon Pakistan to put to an end immediately…[this] act of aggression against India.[2]

Pakistan responded with their own letter to the UN Security Council on 15 January 1948 (S/646), rejecting India’s claims, outlining its own position concerning Kashmir and airing several other grievances regarding India’s conduct.

Much to India’s indignation, the UN Security Council did not order Pakistan to withdraw but instead passed Resolution 39 on 20 January 1948 establishing the UN Commission for India and Pakistan (UNCIP). The UNCIP was empowered to investigate the facts on the ground and act as a mediator between India and Pakistan and to resolve the dispute (S/RES/39). Notwithstanding the Security Council’s efforts, combat operations began to resume in February, with both sides clashing as soon as the territory began to thaw. After a few months of deliberation, the UN Security Council passed the more detailed Resolution 47 on 21 April 1948 in an effort to provide the basic guidelines for resolving the conflict. In essence, Resolution 47 called upon Pakistan to secure the withdrawal of its proxies, followed by a withdrawal of Indian troops. The UN would then establish a temporary Plebiscite Administration in Kashmir, with the mandate to conduct a fair and impartial plebiscite ‘on the question of the accession of the State to India or Pakistan’ (S/RES/47). To oversee the implementation of this Resolution, the UNCIP was expanded and immediately dispatched to the subcontinent.

UN Involvement in the Jammu and Kashmir Dispute

The clear intention of Resolution 47 was to put into practice the principle of self-determination. However, in practice the question of self-determination was quickly superseded by concerns about international peace. Indeed, by the time the UNCIP arrived in July, on the 20 April 1948 Jinnah which authorised the Pakistan Army to occupy the territory held by their tribal proxies and pro-Pakistani rebels, had begun to be pushed back by an Indian offensive. Although this order was given prior to Resolution 47, Pakistan disregarded the UN Resolution’s call for a ceasefire and withdrawal, with Pakistani Army units arriving in force in May. Hence, the UNCIP considered its duty first and foremost to be brokering a truce between India and Pakistan rather than any efforts to determine the Kashmiris’ desires or even lay the groundwork for a plebiscite. To that end, the Commission passed a resolution on 13 August 1948 proposing that both sides issue a ceasefire and accept a truce overseen by the UN (S/1100, 28–30). However, this plan was largely unimaginative, with the UNCIP simply proposing that the ceasefire be monitored by UN observers before reiterating the model for resolving the dispute outlined in Resolution 47.

Although both India and Pakistan eventually agreed to a ceasefire and a Line of Control, which came into effect on 1 January 1949, the UNCIP was unable to broker any agreement as to how to demilitarise Kashmir or how the plebiscite should be conducted (Snedden 2005, 72–74). Pakistan remained unwilling to withdraw its forces, believing that India had attempted to seize Kashmir using ‘fraud and violence’ and would not uphold its obligations (Subbiah 2004, 178–179). Pakistan therefore insisted upon more details as to how the plebiscite would be held and for any Pakistani withdrawal to be synchronised with India’s military (see Annex 1 in S/1196, 12–14). India for its part took the position that the Instrument of Accession made Kashmir legitimately part of India and that Pakistan had launched an unprovoked war of aggression to annex the territory. Hence, India considered that it was the UNCIP’s role to force Pakistan to withdraw, refusing to move before Pakistan and remaining lukewarm on the necessity of holding a plebiscite (Hajari 2015, 246).

Although the UNCIP’s focus had quickly turned to ending the war between India and Pakistan, it did at least attempt to uphold the principle of self-determination by continuing to insist on holding a plebiscite. However, the history of multiple UN efforts to implement the plebiscite in Kashmir illustrates how it was already beginning to defer to the norm of state sovereignty whenever it clashed with the principle of self-determination. This policy approach manifested in two significant ways. Firstly, the UNCIP and its successors largely neglected to consult or otherwise engage with the various political actors within Kashmir itself. It is recorded that some UNCIP members did stay in Srinagar from 1 to 9 September 1948, during which time they met with Sheik Abdullah at least once (S/1100, 75). However, there is no mention or elaboration of what was discussed or observed. The Commission also reported receiving several letters and having an ‘informal’ meeting with the pro-Pakistan ‘Azad Kashmir Government’ (S/1100, 15 and 41).

Regardless, it is evident that the Commission paid little heed to these Kashmiri authorities, disregarding their calls to place greater emphasis on the plebiscite and recognising them only as ‘local authorities’ (Snedden 2013, 88–89). Although the UNCIP formally recognised Sheik Abdullah as the ‘Prime Minister of the State of Jammu and Kashmir’, it mostly avoided engaging with him and his administration throughout their time on the subcontinent. The UNCIP also went to great lengths to avoid indirectly bestowing any legitimacy upon the Azad Kashmir officials, explicitly resolving to ‘avoid an action which might be interpreted as signifying de facto or de jure recognition of the “Azad Kashmir Government”’ (S/1100, 25). There is no evidence that the UNCIP attempted to meet, interview or correspond with Maharaja Hari Singh. These decisions by the UNCIP to disregard these ‘local authorities’ clearly stemmed from its belief that its mandate was to mediate between the governments in New Delhi and Karachi rather than identifying the preferences of Kashmiris. Hence, in choosing to recognise India and Pakistan as the only parties to the dispute, UNCIP was deferring to the norm of state sovereignty rather than engage in a genuine effort to advance the principle of self-determination.

Secondly, the UNCIP and the Security Council clearly considered the Kashmir conflict to be simply a territorial dispute between India and Pakistan. Hence, at no point does the Security Council or its agents appear to have countenanced any option of independence for Kashmir. Indeed, there is no mention in any of the UNCIP’s three reports (S/1100, S/1196 and S/1430) of even a discussion over whether the proposed plebiscite should include an option other than a straightforward vote as to which state to join. Yet this is in stark contrast to the wishes of the dominant political force in Kashmir during this period, Sheik Abdullah. Although Abdullah clearly favoured India over Pakistan, he seemingly preferred to achieve Kashmiri independence or, failing that, ensure that Kashmir effectively remains a semi-autonomous protectorate rather than a regular state of India (Lamb 1991, 191–195). Indeed, during this period, Abdullah frequently argued, to any foreign dignitary that would listen, the necessity of including the option for independence on any plebiscite so that the people of Kashmir could determine where their ‘true well-being lies’ (Lamb 1991, 189 –190; Snedden 2005, 83). It is unclear what support the option for independence had amongst the majority of Kashmiris.

Nonetheless, the point still stands that having the option in a plebiscite would have more holistically encompassed their right to determine their political destiny that is at the heart of the principle of self-determination. In disregarding such sentiments, the UNCIP and the Security Council were, intentionally or not, accepting that India and Pakistan were the sole successor states of British India and thereby tacitly implementing the principle of uti possidetis even at this early stage.

In December 1949, the UNCIP submitted its final report to the Security Council in which it frankly acknowledged its failure to mediate the dispute between India and Pakistan or convince them to demilitarise. Although, the UNCIP maintained that a plebiscite remained the most effective means of determining legitimate sovereignty over Kashmir, it did state that the framework established in Resolution 47 was already ‘a rather outmoded pattern’ and suggested that their successors should consider alternative methods of resolution, including arbitration (S/1430, 78–79). Hence, the Security Council decided to appoint what turned out to be a series of individual representatives empowered with greater flexibility to mediate between India and Pakistan and try to pave the way for the plebiscite.

Arguably the most notable of these was the Australian judge and diplomat, Sir Owen Dixon. Although Dixon, like all the Security Council’s delegations, dealt primarily with the governments of India and Pakistan, he was unique in that he based himself in Srinagar for a full month between June and July 1950. Interestingly, Dixon notes that he had ‘more than one interview with Sheik Abdullah’ but, like the UNCIP, he did not elaborate as to what was discussed during them (S/1791, 3). During his stay in Kashmir, Dixon travelled extensively throughout the disputed territory and therefore recognised more clearly than other UN officials that the straightforward plebiscite outlined in Resolution 47 was unworkable. Indeed, he noted in his report that ‘the State of Jammu and Kashmir is not really a unit geographically, demographically or economically. It is an agglomeration of territories brought under the power of one Maharajah’ (S/1791, 28). Indeed, it was evident that the Buddhist Ladakhi and the Hindu Dogra minorities feared being oppressed by a Muslim Kashmiri majority, whether this was in Pakistan or as part of an independent Kashmir (Behera 2006, 109–114).

In response to this issue, and the seeming inability of India and Pakistan to agree on virtually anything, Dixon proposed that the plan for the plebiscite outlined in Resolution 47 be modified in order to resolve the Kashmir dispute. Specifically, Dixon argued that the situation within Kashmir ultimately required that it be partitioned and suggested two potential models for how to do so. The first proposed breaking the former Princely State into different ethno-nationalist regions which would vote as to which country they would prefer. The second model proposed simply allocating those areas that were certain to prefer accession to either India or Pakistan respectively and then holding a plebiscite in the uncertain territory of the Valley of Kashmir itself (S/1791, 17–18). Though the Indian government initially indicated it was willing to explore a division of Kashmir, Pakistan refused to divert from the original plebiscite plan ensuring that Dixon’s suggestions were ultimately rejected by both states. The UN Security Council also proved unwilling to force the issue and simply continued to exhort the two feuding states to continue negotiations (Snedden 2005, 75).

After Dixon, the UN Security Council appointed two further representatives to ensure the ceasefire held, and tried to induce India and Pakistan to demilitarise Kashmir so the plebiscite could be held or to find some other way around the impasse. However, neither seriously engaged the local Kashmiri authorities, and instead fruitlessly attempted to coax the increasingly disinterested and sceptical India and Pakistan into some form of agreement (Lamb 1991, 175–178). India’s willingness to hold the plebiscite quickly waned as it began to realise that it was unlikely to win any popular vote regarding Kashmir’s accession. Furthermore, India grew increasingly truculent and obstructionist towards any UN proposals, believing that the Security Council generally, and Britain and the US especially, were biased towards Pakistan (Ankit 2010; Hingorani 2016, 192–217). Though Pakistan was ostensibly more amenable to holding a plebiscite, it remained distrustful of India and refused to make any first move. The prospects of holding a successful plebiscite were further spoiled by the frequent and ruthless suppression of Kashmiri rights on both sides of the Line of Control soon after the 1949 ceasefire. India organised the dismissal and arrest of Sheik Abdullah in 1953 for his pro-independence stance, replacing him with a series of pro-Indian puppets who were kept in office via allegedly rigged elections (Lamb 1991, 199–204; Snedden 2005, 75). Pakistan similarly began administering the areas of Kashmir it controlled autocratically, establishing a puppet government in Azad Kashmir and governing the northern areas of Gilgit and Baltistan directly.

In late-1954, Nehru unilaterally declared that the US’s alliance with Pakistan had ‘changed the whole context of the Kashmir issue’ and that the plebiscite was no longer an option that India supported (Snedden 2005, 75–76). The UN Security Council eventually responded by passing Resolution 122 in January 1957, which expressed the UN’s frustration with the lack of progress and restated its position that the future of Kashmir could only be decided by a free and fair plebiscite (S/RES/122). However, the UN remained unwilling to force the issue by imposing sanctions or other measures that would undermine state sovereignty. Gradually the UN gave up trying to enact the principle of self-determination for Kashmir. In 1958, the UN neglected to appoint another representative for India and Pakistan, effectively washing its hands of the issue. Indeed, during both the 1965 and 1971 India-Pakistan wars, the Security Council only passed resolutions demanding a ceasefire between the two sides, making no reference to the people of Kashmir or the right to self-determination (see S/RES/211 and S/RES/307).

The UN, Self-Determination and Jammu and Kashmir Today

As the case of Kashmir demonstrates, the UN’s deference to state sovereignty over the principle of self-determination was demonstrated early in its history. Whilst there was the possibility for the UN to have strengthened the principle of self-determination during its earlier years, that moment has well and truly passed. By the 1970s, the debates within the UN General Assembly and Security Council established the principle that only colonised peoples had an explicit right to self-determination. This position has led supporters of India’s position, especially to point out that Kashmir is not a colony and therefore the arguments for Kashmiri self-determination do not apply (Hingorani 2016, 166–171; Saini 2001, 72–73). Although the UN Security Council has largely accepted this logic and disengaged from the Kashmir conflict, it does continue to maintain a formal interest in the form of the UN Military Observer Group in India and Pakistan, which continues to monitor activities on both sides of the Line of Control.

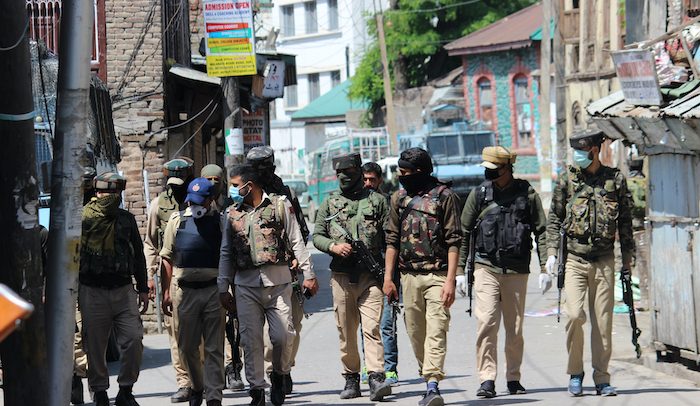

In recent years, the focus of the UN has again turned to Kashmir, albeit due to the human right concerns rather than engaging in any effort to uphold the principle of self-determination. Since 1989, a medium-intensity insurgency has raged in Indian Administered Kashmir, triggered in large part by desires for greater self-determination and Kashmiri frustration over India’s erosion of local autonomy. Although the Kashmir insurgency was originally driven by secessionist sentiments, it was quickly hijacked by Islamist insurgents several of whom were supported by Pakistan. India’s response has been draconian only serving to alienate much of the Kashmiri population (Mohan et al. 2019). A new wave of unrest erupted in 2016 after Indian security forces killed Burhan Wani, a young and popular local insurgent commander, and the Indian Army and paramilitary police responded with crackdowns. This prompted the first significant UN action on Kashmir in decades, with the UN Human Rights Commission (UNHRC) publishing a report identifying numerous human rights abuses committed by the Indian Army during its efforts to crush the unrest (OHCHR 2018). While the UNHRC report also addressed similar issues in Pakistan Administer Kashmir, India strongly rejected the findings of the report, declaring it to be fallacious, prejudiced and a violation of its ‘sovereignty and territorial integrity’ (MEA 2018). In response, the UNHRC simply stated it was ‘disappointed’ with India’s reaction to the report, with the General Assembly and Security Council taking no action or making any comment (Mohan 2018).

On 5 August 2019, the last vestiges of Kashmiri self-determination in India were removed when the recently re-elected Bharatiya Janata Party government placed Kashmiri political leaders under house arrest, revoked the articles in the Indian Constitution which made Kashmir an autonomous Indian state and broke Ladakh off to be an independent province. Although Kashmiri self-determination has been eroded by Indian centralisation efforts in the past, this move makes Kashmir a Union Territory that will be directly administrated from New Delhi, albeit with its own legislature to handle local issues (BBC 2019; Rej 2019). Pakistan vehemently condemned India’s move, pledging to raise the issue at the UN Security Council and potentially take it to the International Court of Justice (Hashim 2019). Pakistan eventually convinced its tacit ally China to call for an emergency closed door session of the Security Council on 16 August 2019, marking the first time in decades that the UN body had directly considered the Kashmir issue. However, the Council ultimately took no action, and instead urged both sides to ‘refrain from taking any unilateral action which might further aggravate the…situation’ (UN News 2019). The UN Secretary-General, Antonio Guterres, also released a statement appealing for ‘maximum restraint’ and reiterating the UN’s position that ‘the status of Jammu and Kashmir is to be settled by peaceful means, in accordance with the UN Charter’ (UN News 2019).

These exchanges are characteristic of the UN’s conduct towards issues of self-determination more generally; the UN’s inherent preference over upholding state sovereign rights ensures that it remains reluctant to act or even pressure an existing sovereign state over issues of self-determination. Generally speaking, this stance by the UN has helped maintain international peace by establishing the state’s post-colonial borders as a clear and workable template for resolving interstate disputes. However, the UN’s commitment to non-interference and the principle of uti possidetis also means that the UN remains far from being a friend of self-determination as such. Rather, the UN’s position often ensures that any aspirant self-determination movement’s demands need to be accepted by existing sovereign state(s) before the international community can even formally engage with them. Thus, most contemporary self-determination movements frequently develop an antagonistic, if not outright combative, relationship with the state(s) they reside in, as the case of Kashmir also ultimately demonstrates. Without some dramatic change of heart from India, Pakistan or the UN Security Council, the people of Kashmir are unlikely to see an end to the stalemate or any genuine chance to choose their destiny anytime soon.

Notes

[1] Apart for the situation in Kashmir, two of the most notable examples from this period are the UN General Assembly’s 1947 vote to accept the partitioning of Palestine (A/RES/181B[II]) and 1950 vote to accept the federation of Ethiopia and Eritrea (A/REES/390A[V]), over the objections of the Arab and Eritrean populations respectively.

[2] The Article 35 referred to in India’s letter is part of Chapter VI of the UN Charter which stipulates that the Security Council has the right to investigate any international dispute or situation likely to endanger international peace (Article 34) and recommends appropriate procedures or terms to resolve the dispute (Articles 36, 37 and 38).

References

Ankit, Rakesh. 2010. “1948: The Crucial Year in the History of Jammu and Kashmir.” Economic and Political Weekly 45 (13): 49–58.

BBC. 2019. “Article 370: India strips disputed Kashmir of special status.” BBC, August 5, 2019. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-49231619.

Behera, Navnita Chadha. 2006. Demystifying Kashmir. Washington D.C.: Brookings Institution Press.

Chandhoke, Neera. 2008. “Exploring the Right to Secession: The South Asian Context.” South Asia Research 28 (1): 1–22.

Hajari, Nisid. 2015. Midnight’s Furies: The Deadly Legacy of India’s Partition. Stroud: Amberly Publishing.

Hashim, Asad. 2019. “Pakistan’s Khan Calls for International Intervention in Kashmir” Al Jazeera, August 6, 2019.

Hingorani, Aman M. 2016. Unravelling the Kashmir Knot. New Delhi: SAGE Publications India.

Lamb, Alastair. 1991. Kashmir: A Disputed Legacy, 1846–1990. Hertingfordbury: Roxford Books.

Makinda, Samuel. 1998. “The United Nations and State Sovereignty: Mechanism for Managing International Security.” Australian Journal of Political Science 33 (1): 101–115.

Ministry of External Affairs (MEA), Government of India. 2018. “Official Spokesperson’s response to a question on the Report by the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights on ‘The human rights situation in Kashmir’.” June 14, 2018.

Mohan, Dinesh, Harsh Mander, Navsharan Singh, Pamela Philipose, and Tapan Bose. 2019. Dateline Kashmir: Inside the Worlds most Militarised Zone. Clayton: Monash University Press.

Mohan, Geeta. 2018. “India’s reaction to Kashmir report disappointing, says human rights body.” India Today, July 18, 2018.

OHCHR. 2018. Report on the Situation of Human Rights in Kashmir: Developments in the Indian State of Jammu and Kashmir from June 2016 to April 2018, and General Human Rights Concerns in Azad Jammu and Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan. UN: Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Countries/IN/DevelopmentsInKashmirJune2016ToApril2018.pdf.

Rej, Abhijnan. 2019. “Modi-fying Kashmir: Unpacking India’s Historic Decision to Revoke Kashmir’s Autonomy” The Diplomat, August 6, 2019. https://thediplomat.com/2019/08/modi-fying-kashmir-unpacking-indias-historic-decision-to-revoke-kashmirs-autonomy/.

Saini, R.S. 2001. “Self-determination, Terrorism and Kashmir.” India Quarterly 57 (2): 59–98.

Schofield, Victoria. 2000. Kashmir in Conflict: India, Pakistan and the Unending War. London: I.B. Tauris.

Snedden, Christopher. 2005. “Would a plebiscite have resolved the Kashmir Dispute?” South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 28 (1): 64–88.

Snedden, Christopher. 2013. Kashmir: The Unwritten History. Noida UP: Harper Collins Publishers India.

Subbiah, Sumathi. 2004. “Security Council Mediation and the Kashmir Dispute: Reflections on its Failures and Possibilities for Renewal.” Boston College International and Comparative Law Review 27 (1): 173–185.

Taras, Raymond C. and Rajat Ganguly. 2006. Understanding Ethnic Conflict. 4th ed. Abington: Routledge.

UN News. 2019. “UN Security Council discusses Kashmir, China urges India and Pakistan to ease tensions.” UN News, August 16, 2019.

https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/08/1044401.

UNCIP, United Nations Commission in India and Pakistan Interim Report, S/1100 (9 November 1948), available from https://undocs.org/S/1100.

UNCIP, United Nations Commission in India and Pakistan Second Interim Report, S/1196 (10 January 1949), available from https://undocs.org/S/1196.

UNCIP, United Nations Commission in India and Pakistan Third Interim Report, S/1430 (9 December 1949), available from https://undocs.org/S/1430.

United Nations. 1945. Charter of the United Nations and the Statute of the International Court of Justice. San Francisco: United Nations Press. https://treaties.un.org/doc/publication/ctc/uncharter.pdf.

United Nations, Security Council, Letter from the Representative of India Addressed to the President of the Security Council, Dated 1 January 1948, S/628 (2 January 1948), available from https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/468605/files/S_628-EN.pdf.

United Nations, Security Council, Letter from the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Pakistan Addressed to the President of the Security Council Dated 15 January 1948 Concerning the Situation in Jammu and Kashmir, S/646 (15 January 1948), available from https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/469219/files/S_646-EN.pdf

United Nations, Security Council, Report of Sir Owen Dixon, United Nations Representative for India and Pakistan, to the Security Council, S/1791 (15 September 1950), available from https://undocs.org/S/1791.

United Nations General Assembly Resolution 181(II)/47, Future Government of Palestine, A/RES/181(II) (29 November 1947), available from https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/181(II).

United Nations General Assembly Resolution 390(V)/50, Eritrea: report of the United Nations Commission for Eritrea; report of the interim Committee of the General Assembly on the report of the United Nations Commission for Eritrea, A/RES/390(V) (2 December 1950), available from https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/390(V).

United Nations General Assembly Resolution 1514(XV)/60, Declaration on the granting of independence to colonial countries and peoples, A/RES/1514 (XV) (14 December 1960), available from https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/1514(XV).

United Nations General Assembly Resolution 2625(XXV)/70, Declaration on Principles of International Law concerning Friendly Relations and Co-operation among States in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations, A/RES/2625 [XXV] (24 October 1970), available from https://www.un.org/ruleoflaw/files/3dda1f104.pdf.

United Nations Security Council. 1948. The India-Pakistan Question, S/RES/39 (20 January 1948), available from https://undocs.org/S/RES/51(1948).

United Nations Security Council. 1948. The India-Pakistan Question, S/RES/47 (20 April 1948), available from https://undocs.org/S/RES/51(1948).

United Nations Security Council. 1948. The India-Pakistan Question, S/RES/51 (3 June 1948), available from https://undocs.org/S/RES/51(1948).

United Nations Security Council. 1957. The India-Pakistan Question, S/RES/122 (24 January 1957), available from https://undocs.org/S/RES/122(1957).

United Nations Security Council. 1965. The India-Pakistan Question, S/RES/211, (20 September 1965), available from https://undocs.org/S/RES/211(1965).

United Nations Security Council. 1971. The India/Pakistan Subcontinent, S/RES/307 (21 December 1971), available from https://undocs.org/S/RES/307(1971).

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – Looking Behind the Delimitation Exercise in Jammu and Kashmir

- The Precarious History of the UN towards Self-Determination

- Observing Kashmir’s first Post-Autonomy Elections

- From Militancy to Stone Pelting: The Vicissitudes of the Kashmiri Freedom Movement

- Opinion – Speaking Truth to Power in Kashmir

- The United Nations and Self-Determination in the Case of East Timor