In February, the US and the Taliban reached an agreement to put the two sides on a path to ending the Afghan War. Despite concerns over the feasibility of the deal, some praised it as a new way to finally bring an end to almost two decades of violence. One component missing from the agreement was any discussion of International Humanitarian Law (IHL) In the past, the Taliban has disregarded IHL. The ability to incorporate IHL could have spared Afghan citizens from terror, even if the fighting did not cease. This piece evaluates how IHL could have been a part of the deal.

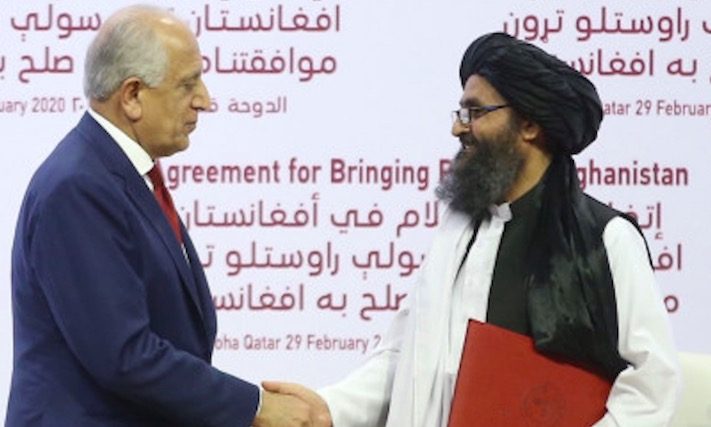

In September 2018, U.S. special peace envoy Zalmay Khalilzad began holding peace talks with the Taliban. The talks were heading towards success until an act of terrorism killed a US soldier in Kabul in September 2019, which led US President Donald Trump to proclaim any potential deal ‘dead.’ In December 2019, Khalilzad began holding talks with the Taliban again, where he proposed a temporary peace talk. By the end of December, there were reports that the Taliban had agreed to a temporary cease-fire, but the details were unknown.

On February 14, the cease-fire was revealed. It was a seven-day agreement to reduce violence, with a promise to work towards a formal peace deal. The deal began on February 21. It was unclear what the reduction in violence meant, but it was seen as a trial for the US agreeing to a peace deal with the Taliban on February 29. In the week after February 21, top US and Afghanistan military officials walked the previous war-torn streets of Kabul to demonstrate the safety of the city following the agreement and how much faith they had in the agreement.

On February 29, 2020, the US and the Taliban announced a peace deal. The deal did not provide immediate guarantees for a cease-fire but said a ‘permanent and comprehensive ceasefire will be an item on the agenda of the intra-Afghan dialogue and negotiations.’ Moreover, the agreement said the US would reduce its troops in the region from 12,000 to 8,600 in the next 135 days and would completely withdraw if the Taliban lived up to its commitments. The Taliban’s commitments included having direct talks with the ruling Afghan government and not threatening American security on top of working towards a permanent cease-fire in the region. The deal also provided that America would release 5,000 Taliban prisoners in exchange for the Taliban releasing 1,000 of their prisoners.

The deal was immediately met with concern in Afghanistan among the general public who worried that they would face danger if Taliban groups regained lost power, but also marginalized groups such as women who feared they would specifically be targeted by the Taliban. Afghan political leaders also feared for the stability of the nation due to the release of Taliban prisoners.

On March 4, the Taliban attacked US forces, providing an embarrassment for Trump who had proclaimed there would be ‘no violence’ in Afghanistan. The US responded with a strike that the US claimed was aimed at disrupting a planned Taliban attack on a security checkpoint in Afghanistan. Since there was no formal agreed upon reduction in violence in the peace agreement, the Taliban did not technically violate the peace agreement. Moreover, some believed that it did not mean that the Taliban was abandoning any chance of a deal, but instead just trying to improve their negotiating position.

It is important to zero in on the fact that the agreement does not have much specification regarding IHL. It only pledges to work towards a ceasefire. It would have provided groundbreaking legitimacy of IHL if the US was able to get the Taliban to agree to the established laws regarding war. IHL is largely governed by international conventions, particularly the Geneva Convention. There are four parts to the Geneva Convention, with two additional protocols, the US has agreed to the four parts, it has not agreed to the additional protocols. While there is a debate to be had whether the US itself should agree to the two additional protocols, even having the Taliban on board with the main four parts of the Geneva Convention would be major improvement of the war. To be a member of the Convention, the member of course has to be a State. The Taliban is not officially a state nor is it the government of a state. However, that does not preclude an organization from volunteering to agree to provisions of the Conventions. The Conventions are extensive. The agreement could have just stated that ‘all warfare between the Taliban and US-Afghan forces will be governed by the Geneva Convention.’ This would be preferable, but it is possible the Taliban would not want be governed by such a lengthy document. If the Taliban would not, then it would be best for the US to try to get the Taliban to agree to specific components of the Geneva Convention. Regardless of which direction it could have taken, there are specific elements that the Taliban routinely violate that Afghanistan would benefit from the Taliban being government under.

First, Convention IV, Article 15 of the Geneva Convention allows for parties to establish ‘neutralized zones’ that protect people such as civilians or even wounded combatants. The Taliban has attacked civilian areas, such as schools and hospitals. The US could have had the Taliban agree not to attack those places or even places known for having civilians gather in. Doing so, could protect thousands of civilians, even if the warfare had to continue.

Additionally, Convention III, Article 13 of the Geneva Convention calls for the ‘Humane Treatment of Prisoners.’ It prohibits ‘physical mutilation’ and ‘acts of violence or intimidation and against insults and public curiosity.’ The Taliban has committed ‘acts of violence’ against prisoners and have put it on for public display through recorded beheadings of prisoners of war. Having the Taliban agree to this would at least ensure that if US-Afghan forces were going to die at the hands of Taliban forces, they would not have to go through the humiliating and traumatic treatment so many Afghan and US soldiers have had to go through.

There are a few reasons why the US might have not included these components in the agreement. The first is that the US does not necessarily abide by these components. Regarding keeping civilians out of harm’s way, the US has been responsible for thousands of Afghan civilian deaths. Though a UN study found that US accounted for only eight percent of deaths last year, that is still hundreds of civilian deaths. While the US is not purposefully targeting civilian locations as the Taliban has, many have argued the US could take further precautions to avoid civilian deaths, Amnesty International even called on both the US and the Taliban agree to refrain from killing civilians as part of the deal. In regards to torture, the US has been accused of torture, so much so that the International Criminal Court held hearings on the matter in December, 2019. Again, though the US is not beheading Taliban prisoners, it still could be found in violation of the Geneva Convention. Alternatively, the US could have included watered down language inspired by the Geneva convention such as ‘no targeting hospitals and schools’ or ‘no beheadings.’ The issue here is that it would be exclusively targeted at the Taliban and the Taliban would likely expect the US to give something in return.

Another issue is enforcement. When a state violates IHL, there are several ways to enforce the international obligations. The violations of IHL can be grounds for sanctions, such as when sanctions were used against Syria for Syria violating IHL by using chemical weapons. Given that the Taliban is not a state, there are not really sanctions that could apply to the Taliban. The US could offer conditional financial assistance that it could pull if the Taliban violated the IHL provisions, but it is unlikely that the US would want to provide money to a terrorist group working against the Afghan government and US.

The agreement between the US and Taliban provides some hope for ending what has been decades of violence. It also provides a potential development within IHL that if terrorist groups can be negotiated with to at least curb their violence, if not end it, countless lives could be saved. However, to get to that point, it is best to start with incremental agreements over tactics, rather than a vague goal of ending violence in the region. By not providing specific provisions to curb the Taliban’s warfare tactics and get them to agree to IHL like provisions, the US missed out on an opportunity prevent further violence in this instance and set a precedent for future wars.