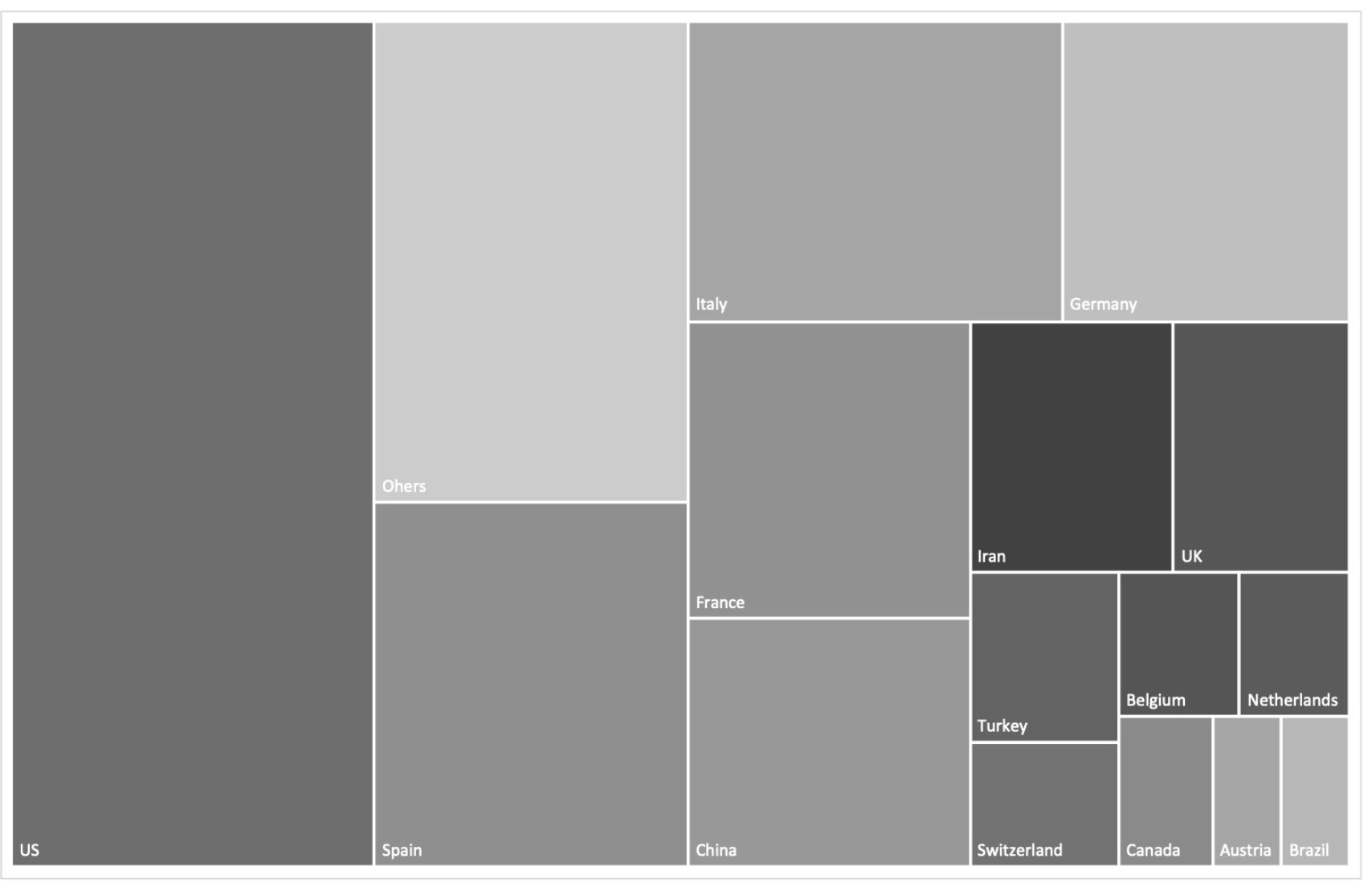

Over the last 100 years, there have been seven global pandemics, such as Spanish flu, Asian flu, Hong Kong flu, H1N1, Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) and Ebola. Nevertheless, with the novel coronavirus/Covid-19 the global economy is experiencing a health crisis, unprecedented human and economic in the last century (ECLAC, 2020). Of the 1.7 million global cases and 104,000 global deaths at the time of publication, at the time of writing (6 April) there were 1,337,749 cases. The countries with the highest number of confirmed cases were the USA (27.1%), Spain (10.1%) and Italy (9.9%). China was in 6th place (6.2%) and Brazil in 15th place in the ranking (12,056, 0.9%). Regarding the total number of deaths up to the same time as the survey (72,560), Italy (22.8%), Spain (18.1%) and the USA (12.9%) stand out. China occupied the 7th place (4.5%) and Brazil occupied the 13th in the ranking (553, 0.8%). Among the total recovered cases (276,515), Brazil had 127 (0.046%). This article will deny the existing trade-off between health and economic activity, highlighting the uncertainties related to the conjuncture, which stress the role of the Government in the economy.

In order to propose some counter-cyclical economic policies focused on (i) employment, income, and purchasing power; and (ii) monetary policy and public banks, this article will start from an analysis of some macroeconomic aggregates: (i) GPD; (ii) Selic rate; (iii) inflation; (iv) international trade; (v) investment; and (vi) employment, using official Brazilian databases.

Figure 1. Countries share in total COVID-19 cases. Source: Own elaboration based on Coronavirus Resource Center (Johns Hopkins University).

Macroeconomic variables

Opertti and Moreira (2020) point out that the impacts are on the supply side (production of certain goods and services, as well as the labor force itself) and demand side (consumption, limited mobility, and precautionary savings). Several activities related to informal services (self-employed) will be affected and they represent a significant part of the labor market. The next subsections will analyze some macroeconomic aggregates to present the recent Brazilian context.

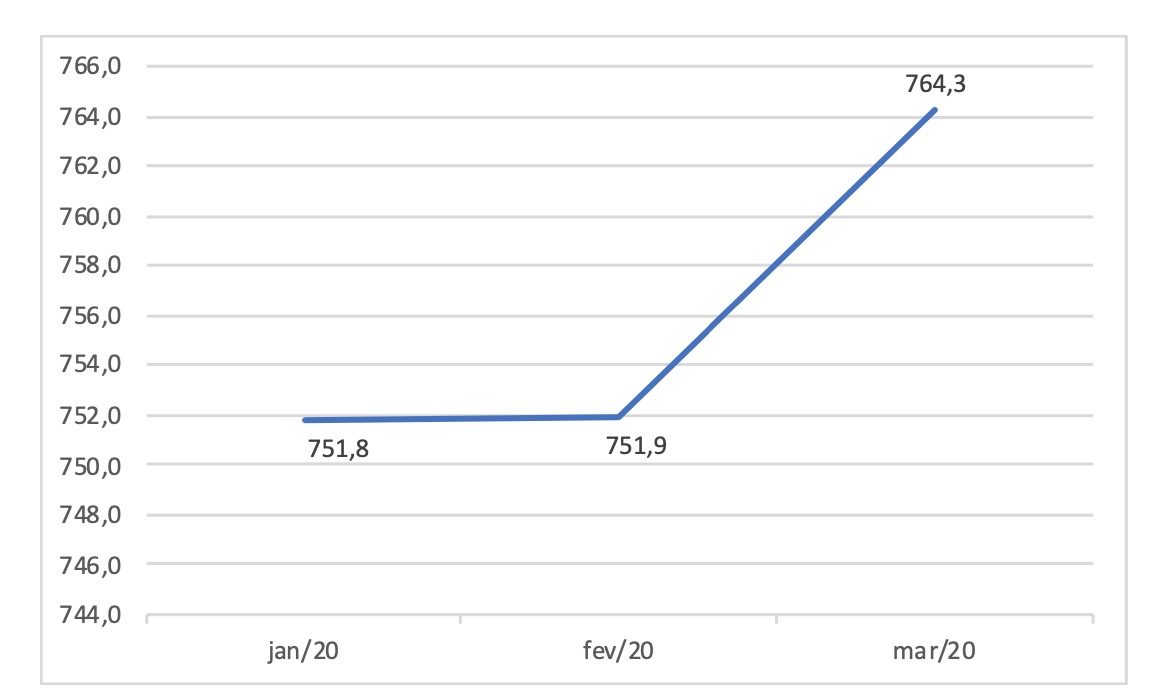

Gross domestic product (GDP) is the total value of the final goods and services produced in the country over a given period of time. Table 1 shows the evolution of Brazilian GDP at market prices, between 2015 and 2019. For 2020, the Bank of America (Bofa) announced on April 2, a contraction of 3.5% in the GDP of 2020, given the sensitivity to the price of commodities (falling for months) and the Chinese demand (main Brazilian trading partner). The Central Bank’s Focus Bulletin pointed out on 06 April a deteriorating trend in market expectations. The GDP growth rate for 2020 drops from +1.99% (4 weeks ago), to -0.48% (1 week ago) and to -1.18% (April 6). The forecasts on 06 April for 2021, 2022 and 2023 are for a steady increase of 2.5% per year (forecast that has remained unchanged in the last month).

Table 1. Evolution of Brazilian GDP at market prices, 2015-2019 (R$ trillion). Source: Own elaboration based on IBGE and Ipeadata. * Average exchange rate calculated from the monthly values of the nominal exchange rate, US$/R$.

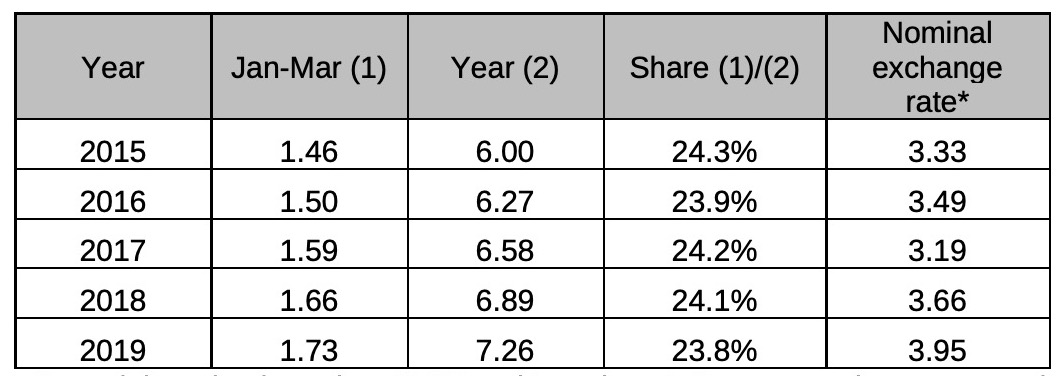

Since the beginning of 2019, the Selic rate, which is Brazil’s basic interest rate, has followed successive declines in the different meetings of the Monetary Policy Committee (Copom), of the Central Bank of Brazil (BCB). It started the year at 6.4%, then it dropped to 5.9% (August 1), 5.4% (September 19), 4.9% (October 31) and 4.4% (December 12). Figure 2 shows the Selic movement in 2020. According to the BCB’s Focus Bulletin, published on 06 April, the Selic target for the end of 2020 drops from 4.25% (4 weeks ago), to 3.50% (1 week ago) and to 3.25 (April 6t). The drop in the short term may contribute to the facilitation of access to credit by families and companies. However, the forecast on 06 April is for the Selic to increase to 4.75% (2021), 6.00% (2022) and 6.00% (2023), which, despite the post-COVID-19, can contribute to attract foreign capital.

Figure 2. Evolution of the Selic rate, Jan-Apr 2020 (% per year). Source: Own elaboration based on BCB

The General Consumer Price Index (IPCA) aims to measure the inflation of a set of products and services sold in retail, having as target families with incomes from 1 to 40 minimum wages, whatever the source, residing in the urban areas of the regions covered (metropolitan regions of Belém, Fortaleza, Recife, Salvador, Belo Horizonte, Vitória, Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, Curitiba, Porto Alegre, besides Distrito Federal, the municipalities of Goiânia and Campo Grande). The BCB’s Focus report, April 6, predicts IPCA for 2020 drops from 3.20% (4 weeks ago) to 2.94% (1 week ago) to 2.72% (April 6).

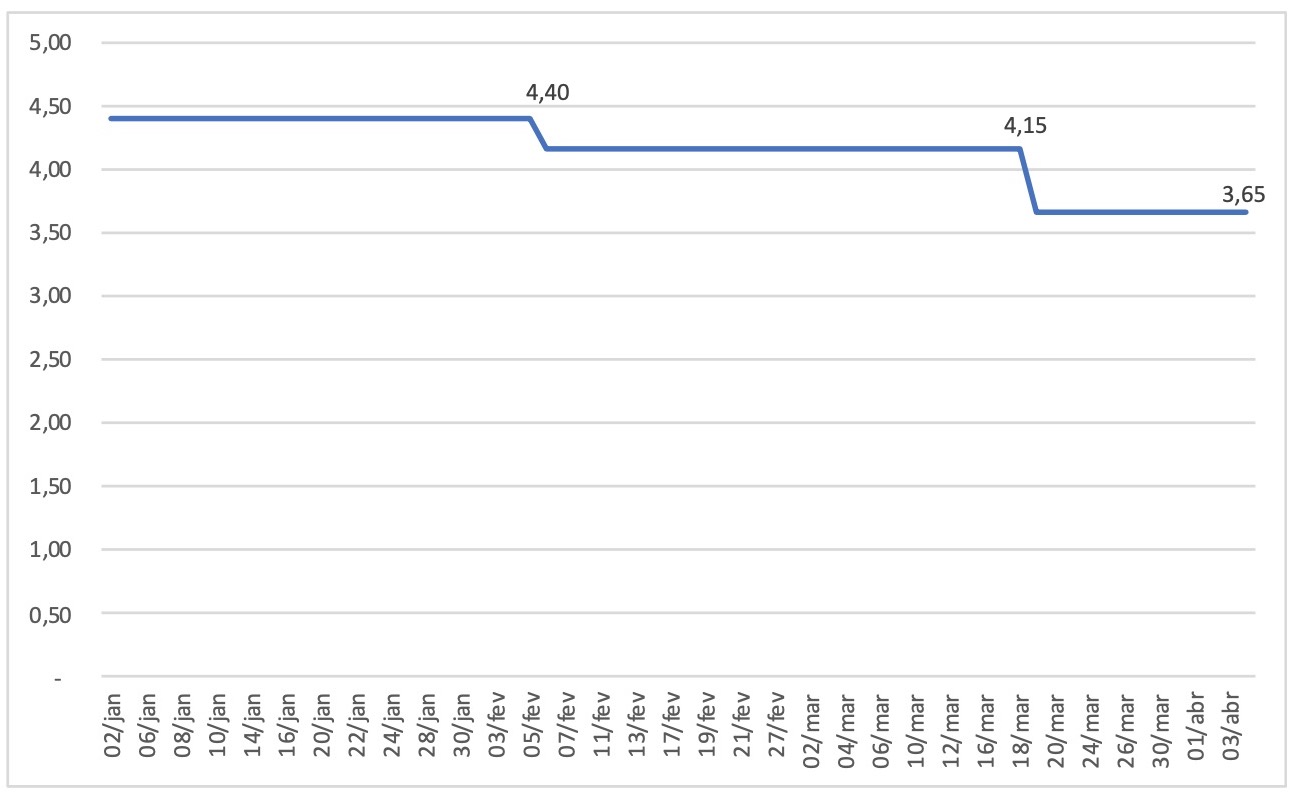

On April 6, the forecasts for 2021, 2022 and 2023 fell from 3.57% to 3.5% (forecast that remains unchanged during the last month). The inflation target to be pursued by the BCB is 4.00% in 2020, 3.75% in 2021 and 3.50% for 2022, always with a tolerance interval of 1.5 percentage points up or down. The Prices General Index – Internal Availability (IGP-DI), calculated by the Getúlio Vargas Foundation (FGV), is a summary measure of national inflation, based on the IPA-DI, IPC-DI and INCC-DI. Figure 3 shows the evolution of the IGP-DI in the first quarter of 2020, published on April 6. It is noticed that the IGP-DI increases only 0.01% between January and February, but it grows 1.64% between February and March 2020.

Figure 3. Evolution of the IGP-DI, Jan-Mar 2020 (% per year). Source: Own elaboration based on FGV IBRE.

When it comes to the weight of food in March 2020, stands out respectively: onion (18.51%), tomatoes (14.84% – had already increased 15.44% in February), vegetables (+12.27 % – had already increased 6.24% in February), garlic (+ 9.70%), potato (+ 9.50%) and eggs (+ 8.40%). The increase in the price of food is particularly worrying, especially given the fall in the average income of Brazilian citizens, especially of low-income families. Besides, this weighs heavily on the families’ budget, as it is the basic diet.

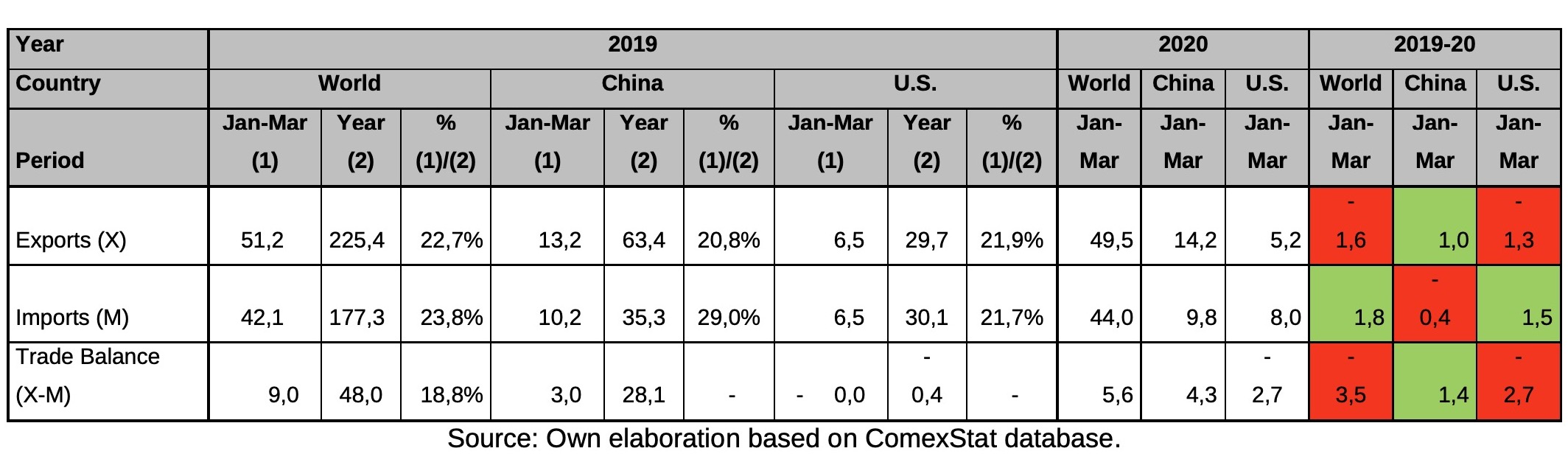

Table 2 shows the evolution of Brazilian exports, imports, and trade balance in billions of US$, both for the first quarter of 2019 and 2020, and for the 2019. It considers the two main trading partners (China and the U.S., respectively), as well as their participation in the total Brazilian international trade. In 2019, China and the U.S. represented 28.1% and 13.2% of the destination of Brazilian exports and 19.9% and 17.0% of the origin of Brazilian imports, respectively. In the first quarter of 2020, the participation of these countries was 28.6% and 10.6%, respectively, in exports, and 22.4% and 18.1%, in imports. What can be seen comparing the first quarter of 2020 to 2019 is that total exports fell by US$ 1.6 billion (-3.2%) and total imports increased by US$ 1.8 billion (+ 4.3%). In the same period, exports to China increased by US$ 1 billion (+7.4%) and imports fell by US$ 400 million (-3.9%), while exports to the U.S. fell by US$ 1.3 billion (-19.3%) and imports increased by US$ 1.5 billion (+22.2%). In general, the Brazilian trade balance in the first quarter of 2020 compared to 2019 fell by US$ 3.5 billion, reaching US$ 5.6 billion.

Table 2. Evolution of Brazilian international trade, 2019-2020 (US$ billions)

According to the BCB’s Focus Bulletin, on April 6, the trade balance for 2020 is expected to fall from US$ 36.4 billion (4 weeks ago), to US$ 35.0 (1 week ago) and to US$ 34,1 (April 6). The forecast on April 6 is the trade balance of US$ 35.0 billion (2021), US$ 34.1 billion (2022) and US$ 28.9 billion (2023). The forecast of a drop in the surplus balance of the trade balance suggests a reduction in the availability of dollars for the Brazilian economy, which, in this scenario, is particularly badly desired.

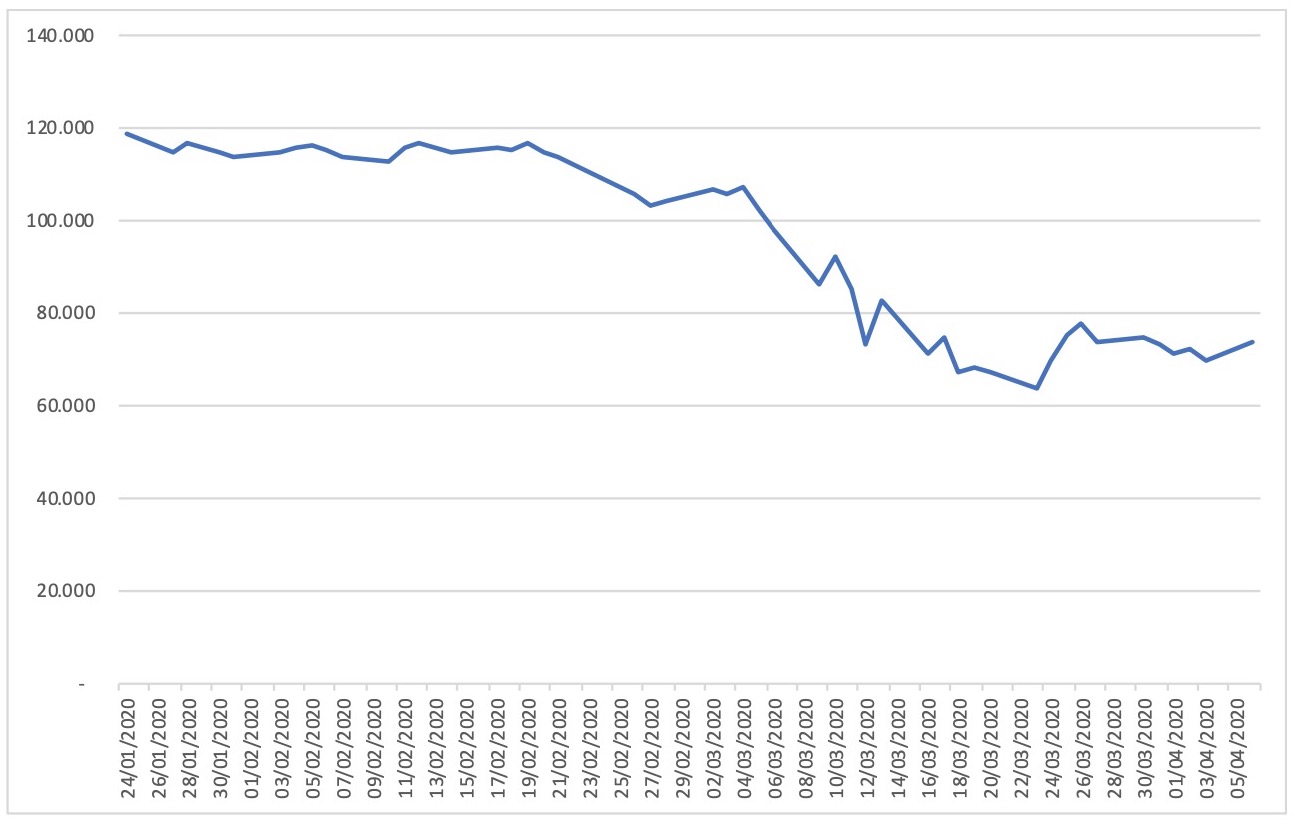

Ibovespa is the main index of the Brazilian stock exchange (B3). Figure 4 highlights the evolution of Ibovespa in the first quarter of 2020, which reached a peak of 118,376 (January 24) and a minimum of 63,570 (March 23, totaling R$ 26.1 billion). It may be understood as a proxy for the dynamics of financial flows in Brazil.

Figure 4. Evolution of the Ibovespa, Jan-Apr 2020 (value*). Source: Own elaboration based on InfoMoney. * Closing prices.

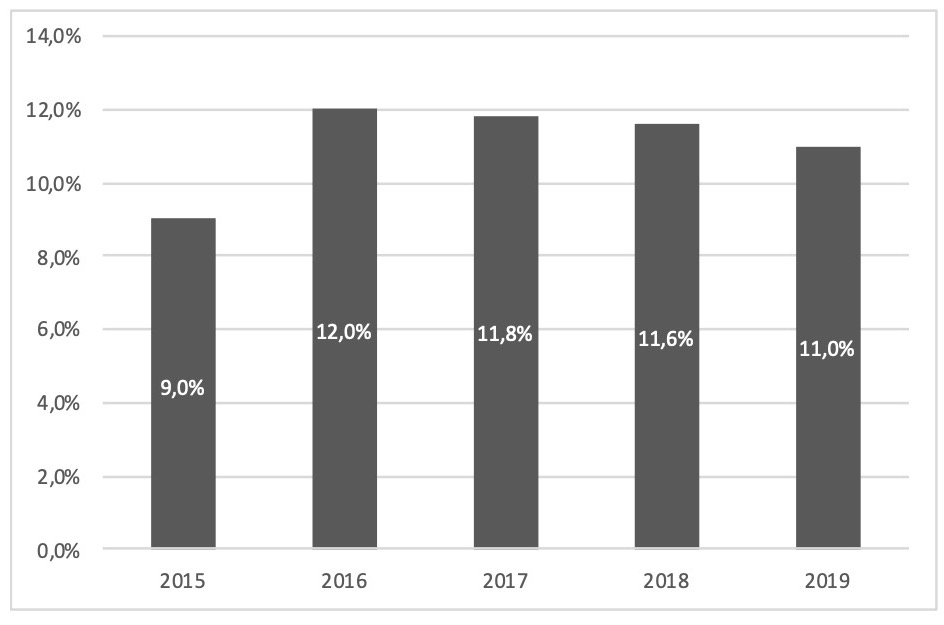

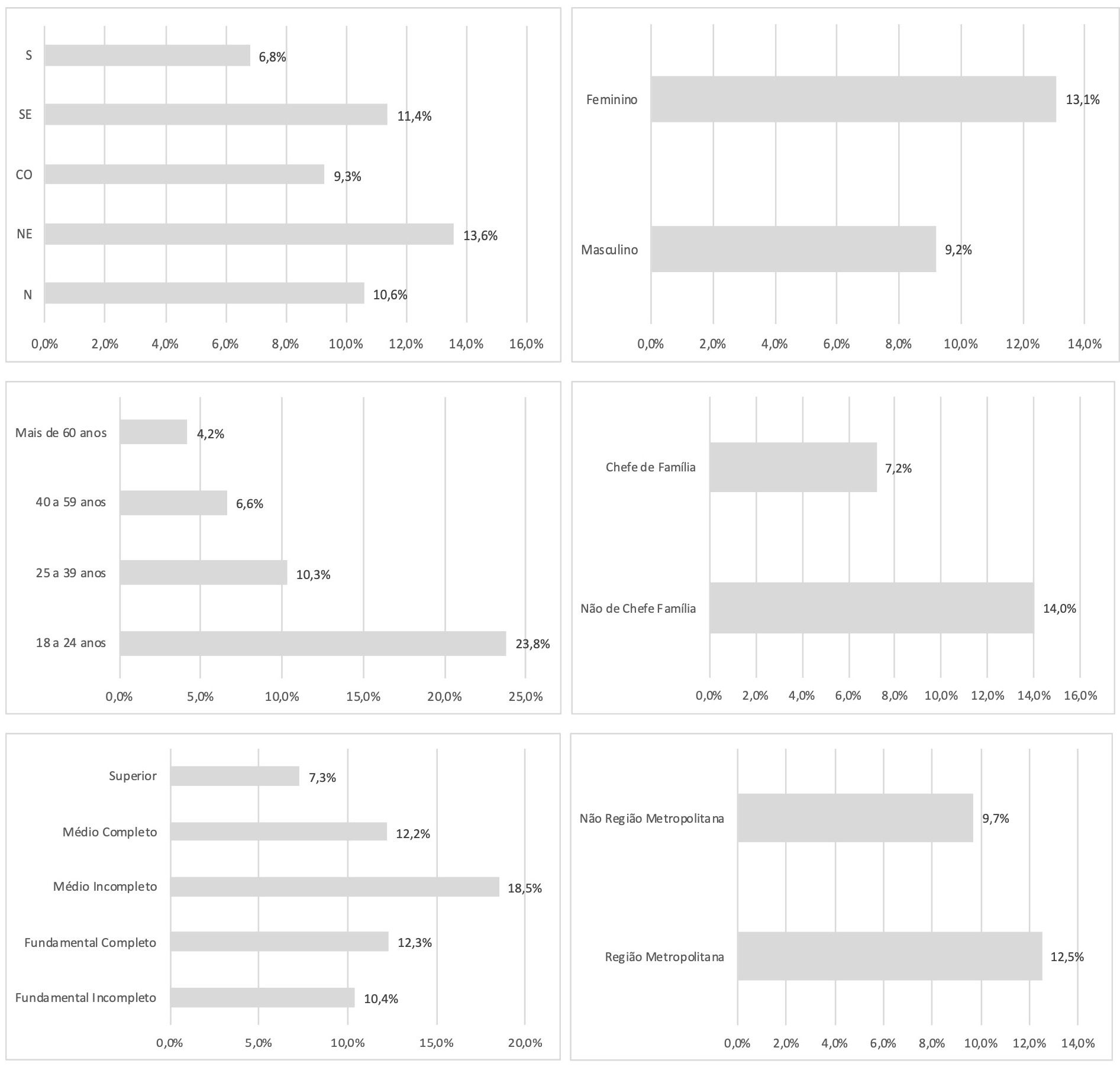

Figure 5. Evolution of the unemployment rate by region, 2015-2019 (%). Source: own elaboration based on PNAD Contínua (IBGE) and Lameiras, Corseuil & Carvalho (2020).

Figure 5 shows the evolution of the unemployment rate by region between 2015 and 2019. Figure 6, composed of six disaggregated graphs, shows the Brazilian unemployment rate in 2019, detailed by region, gender, age group, family position, education, and metropolitan region or not (in%). Regarding region details, high values are observed for the Northeast (13.6%), Southeast (11.4%) and North (10.6%), respectively. With regard to gender, there is a higher unemployment rate among women (13.1%). Regarding the age group, the highest unemployment rate is among the youngest (23.8%), followed by workers between 25 and 39 years old (10.3%), totaling more than a third of unemployment in 2019 – which is reflected in the greater presence in non-household heads (14.0%). Regarding education, the unemployment is proportional to the years of formal education, affecting more the portion of the population without higher education (53.4%). In general, the unemployment rate is higher in metropolitan regions (12.5%), which may explain part of the social problems faced in these regions.

Figure 6. Unemployment rate in 2019, by region, gender, age group, family position, education and metropolitan area or not (%). Source: own elaboration based on PNAD Contínua (IBGE) and Lameiras, Corseuil & Carvalho (2020).

The share of employed persons that came from formality to informality fell from 5.9% to 5.3% between the third and fourth quarters of 2019 (Lameiras, Corseuil & Carvalho, 2020). On March 31, the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) published the Continuous National Household Sample Survey (PNAD Continuous) showing that the informality rate in the labor market dropped to 40.6%, totaling 38 million workers informal. Informality includes workers without a formal contract (11.6 million), domestic workers without a license (4.5 million), employers without a CNPJ (810 thousand), self-employed without a CNPJ (24.5 million) and family workers auxiliaries (1.97 million).

Counter-cyclical economic policies

Economic history reminds us that, in times of crisis, the Government’s relevance in the economy grows significantly – even in countries that preach less economic intervention. The subprime (2008) and eurozone (2010) crises are recent examples of this trend. Nevertheless, part of society and public decision makers seems to suffer from forgetfulness.

The shape of the post-COVID-19 economic recovery curve is currently being discussed: would it be “L”, “V” or “U”? From the point of view of some countries, it would hardly be in a “V” shape, with rapid growth once the confinement period is over, especially due to its medium and long terms impacts. Certainly, the shape of the curve, as well as the recovery of the economy will depend on a mix of factors, among which are the adverse impacts on the population and the economy, the success of the counter-cyclical economic policies carried out in the period, as well as it will depend on extra-economic factors (because COVID-19 can be understood as an exogenous shock).

From the Brazilian point of view, the scenario suggested by the Economic Conjuncture Group, of the Institute of Economics of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (IE/UFRJ) is for a fall of about 4% of GDP for 2020. Like other analysis, this drop in GDP is expected in the first quarter of 2020, followed by a very deep drop in the second quarter – which would consist of a scenario of technical recession (falling in economic growth for two consecutive quarters).

As a suggestion of policies to face the challenge of unemployment, falling income and loss of purchasing power, Brazil proposed, for formal workers: Provisional Measure (MP) 936/2020. It institutes the Emergency Employment and Income Maintenance Program and provides for complementary labor measures to deal with the state of public calamity, allowing companies to reduce 25%, 50%, and up to 70% of employees’ work hours and wages, for up to 3 months. The benefit, which will be paid for with Federal resources, can be paid in the following cases (Art. 5): proportional reduction of working hours and wages; and temporary suspension of the employment contract; exclusively for the duration of the proportional reduction in working hours and wages or the temporary suspension of the employment contract.

On April 3 (last Friday), the Workers’ Party (PT), the Communist Party of Brazil (PCdoB) and the Socialism and Freedom Party (PSOL) asked the Supreme Federal Court (STF) to immediately suspend the effects of the MP 936/2020. For them, the MP exposes the formal worker and violates the Federal Constitution and the Consolidation of the Labor Laws (CLT) by not providing another way of supporting the citizens, removing already consolidated labor rights (union or collective protection in the execution of the agreement or convention) for wage reduction) and the irreducibility of wages (constitutional principle, which could only be removed through collective agreement).

Regarding self-employed and informal workers (without a formal contract), it is necessary that they be covered by public policies. On March 30 (last Monday), the Senate approved a bill that establishes the payment for three months of an emergency aid of R$ 600.00 for workers without a formal contract (including self-employed workers and in an intermittent contract). Known as “coronavoucher”, it is expected to cover 54 million people, with an approximate cost of R$ 98 billion. Emergency assistance applies in the following conditions: being over 18 years of age, meeting family income criteria, not receiving social security benefits, unemployment insurance or participating in income transfer programs from the federal government (with the exception of Bolsa Família).

Women who are mothers and heads of families, and are within the other criteria, may receive R$ 1,200.00 (two quotas) per month. It is noteworthy that the amount initially proposed for the voucher was only R$ 200.00 and that it was sanctioned by President Bolsonaro (April 1), with some vetoes: expansion of the Continuous Cash Benefit Programme (BPC), reassessment of criteria, and restriction to the bank account. In these cases (self-employed, informal workers, and unemployed), it is necessary to consider the difficulty of part of these workers having access to bank accounts and the internet. We suggest an expansion of income transfer programs (such as, for example, Bolsa Família), especially for families with school-age children. In addition, it is essential to readjust the benefit and reduce the waiting time for implementing the benefit.

It is also suggested to relax, ease, or suspend the payment of basic bills (electricity, water, and sewage), rents, fines, interest and penalties during the crisis period in order to reduce pressure on families, which is being proposed by some senators in the form of Law Projects (PL). PL 868/2020 stands out, which proposes the creation of the Emergency Social Tariff for Water, Sewage, and Electricity, with full amnesty for the payment of these services for 90 days, and provides for the prohibition of cuts of these services during the duration of calamity state in national public health (subject to certain limits and parameters).

From the perspective of the Union, it is essential to review established ceilings and make previous projects more flexible. It is necessary to reduce the conflict between the Union, States, and Municipalities, so that the Union provides fiscal aid to the other entities of the federation to face the current crisis. From a business point of view, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) can now request the emergency credit line for payment of employees’ wages for up to two months, created by MP 944/2020. Until April 6, among the five largest banks in Brazil, only Bradesco and Itaú Unibanco had disclosed how the financing request works. Among the benefited SMEs are those that had annual gross revenue between R$ 360 thousand and R$ 10 million, in 2019, that will not be able to fire their employees for 2 months.

The interest on the loan is Selic itself (3.75% per year), with a grace period to pay up to 30 months and the payment is limited to 2 minimum wages (MW) per employee (R$ 2,090.00 – those who earn more than 2 MW will not receive the salary in full), to be deposited directly in their account (without the intermediation of the bosses). The investment volume may reach R$ 40 billion (R$ 20 billion per month), with the expectation of serving around 1.4 million companies and 12.2 million workers. Most of the money (85%) will be injected by the government and the remaining 15% will come from private banks.

We suggested that the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES) act more intensively. So far, totaling R$ 97 billion the amount of credit to face the COVID-19 crisis in Brazil, only R$ 7 billion (7.2%) involves disbursements from BNDES: the working capital line for SME (R$ 5 billion, expanding an existing credit line) and the health line (R$ 2 billion), to expand Brazilian National Health System (SUS) beds and purchase health equipment.

Financing of the private sector from public banks reduces credit risk, especially high in this context of such uncertainty. In 2008, the role of Brazilian public banks was essential to reduce the impacts of the international crisis. There should be greater flexibility and expansion of the health budget in relation to the constitutional minimums (EC 95/2016), with guarantees of additional resources. This is mainly due to the fact that health has been suffering from underinvestment. In line, there should be an increase in investment in research, and science, technology and innovation (ST&I), particularly in the health area (in the short term).

Conclusions

From the analysis of macroeconomic data and counter-cyclical economic policies, the data showed the need to revise the role of the Government, especially with regard to the welfare state. In view of the COVID-19 pandemic, there is consensus among economists about the relevance of spending to face the crisis, so there is no room for fiscal debate on austerity, primary budget surplus and/or golden rule.

In Brazil, measures are advancing day after day, with a certain delay. There is no pre-established limit for government spending, however the public debt resulting from anti-cyclical economic policies must be fair fiscal and socially. It is necessary to deny the argument that there is a trade-off between health and economic activity. Regarding the Government, it should be noted that diplomatic constraints with China are not welcome, given the country’s relevance to the Brazilian economy in terms of trade and investments. Thus, the crisis highlights past problems, such as social inequality, uncoordination between Union entities, low investment in health and education, under-dimensioning of SUS, which leads to the need for reforms. When it comes to the management of additional resources provided, they need to reach the needy citizens, overcoming productive bottlenecks, deficits in infrastructure, as well as in access to technology and the internet.

Finally, measures to deal with the side effects of COVID-19 on the Brazilian economy must consider the asymmetric impacts on society, as well as environmental and climate aspects (especially with post-COVID-19 investments). This is not a war, but an unprecedented humanitarian crisis which highlights the need to strengthen (public) health systems and the social protection system (based on basic income programs, for example). Both are two public goods, with enormous externalities on the economy.

References

ECLAC. 2020. América Latina y el Caribe ante la pandemia del COVID-19: efectos económicos y sociales. Santiago: ECLAC.

Lameiras, M. A. P., Corseuil, C. H. L., Carvalho, S. S. 2020. ‘Mercado de trabalho.’ Carta Conjuntura 46 (1): 1–25.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Bolsonaro’s Brazil in Times of COVID-19: A Necropolitical Pharmakon

- The Pandemic in Brazil: Normality as Necropolitics

- Between Political Crisis and COVID-19: Bolsonaro’s Foreign Policy

- Analyzing Jair Bolsonaro’s COVID-19 War Metaphors

- Opinion – Impacts and Restrictions to Human Rights During COVID-19

- Opinion – How Coronavirus Exposes Unequal Access to Education in America