This article is part of a series.

The advent of lethal autonomous weapon systems (LAWS) presents states with new political, technological, operational, legal and ethical challenges. This paper addresses these various challenges within defined parameters. The principles set out below are framed by the assumptions that underpin IHL and ethics of war traditions, which accept that war is sometimes necessary and can be just, but should be restrained in its practice. It is acknowledged from the outset that there is not the scope here to provide a comprehensive response to every issue raised by LAWS. Inspired by the Montreux Document, the goal here is to provide guiding principles for the development and use of LAWS without taking a position on the broader political and philosophical questions of acceptability of developing and using autonomous weapons.

Principle 1. International Humanitarian Law (IHL) Applies to LAWS

There is agreement among States Parties that IHL applies to the development and use of LAWS. The key principles of IHL, including military necessity, humanity, distinction and proportionality, apply regardless of the type of armed conflict. Several States have domestic policies reaffirming this point. This commitment to IHL principles is key to the development and employment of LAWS. Responsibility for compliance with IHL remains with human operators and cannot be delegated to technology. Therefore, LAWS must be designed so they can be operated in a way that carries out commander’s intent.

Principle 2. Humans are Responsible for the Employment of LAWS

Responsibility for compliance with IHL remains with humans. It is above all vested in operators who employ weapons and is discharged through the military chain of command. Responsibility for the effects (i.e. damage or injury) caused by LAWS cannot be delegated to technology. Weapons or weapons systems, even those which incorporate autonomy, are not legal or moral agents. Machines, even complex ones, such as adaptive self-learning systems, cannot make ethical choices, they can only function in accordance with their programming. It is therefore erroneous to speak of delegating (either legal or moral) responsibility to autonomous weapons or autonomous weapons systems. Human agents retain responsibility for the intended effects and unintended but foreseeable effects caused by LAWS.

Principle 3. The Principle of Reasonable Foreseeability Applies to LAWS

War has always been characterized by an inability to anticipate and prevent every negative outcome. From the challenge of applying Rules of Engagement in complex, uncertain and dynamic environments, to mechanical failures of weapons and munitions, the principle of reasonable foreseeability has shaped human judgements and actions in war. This principle extends to judgements and actions in the development and deployment of LAWS, including individual and command responsibility. As a matter of law, parties to an armed conflict are required to account for the reasonably foreseeable reverberating effects of an attack, particularly for assessments of proportionality and precautions in attack. See Appendix for an example on the authorisation of LAWS for deployment.

Principle 4. Use of LAWS Should Enhance Control over Desired Outcomes

Militaries pursue advances in technology to achieve advantage over likely adversaries. This advantage can come in many forms, but can be broadly categorized into enhancing existing capabilities or developing entirely new capabilities. Pursuit of autonomous capability within weapon systems should be motivated by the desire to achieve at least the same or better quality of decision-making at a more rapid pace, or to achieve a desired outcome when other forms of control are denied. In both cases, autonomous capability should enable greater control over the desired outcome.

Principle 5. Command and Control Accountability Applies to LAWS

Military command and control (C2) is the means by which states control the use of force while complying with their legal obligations and respecting ethical values. Militaries have established C2 procedures, which are fundamental to how they function. Effective C2 enables compliance with IHL. Introducing LAWS into military forces must be done in a way that is coherent with C2 paradigms.

Principle 6. Appropriate Use of LAWS is Context Dependent

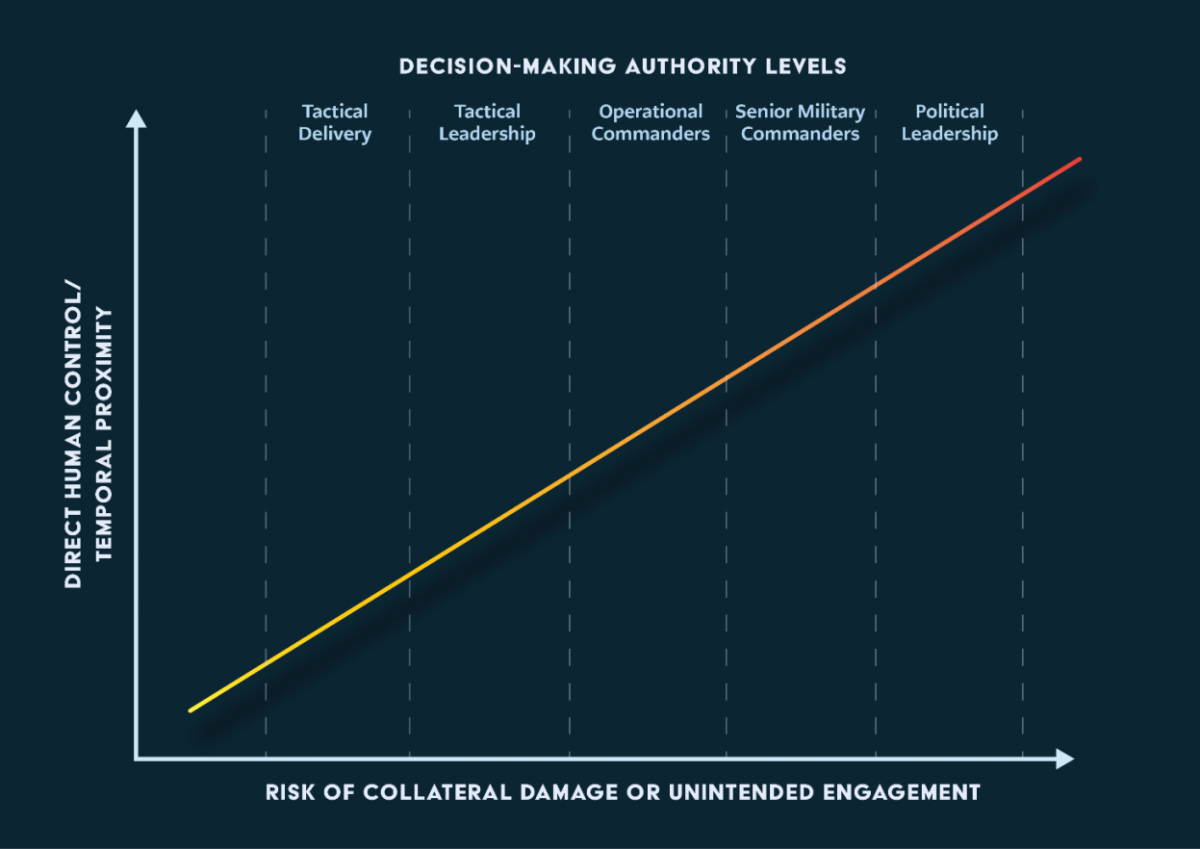

Consistent with other weapon systems, the use of LAWS must be constrained by a) the operational context, and b) the specific capabilities and limitations of the weapon or weapon system in question. IHL requires that military forces take feasible precautions to minimize incidental loss of life to civilians and damage to civilian objects and prohibits any attack which may be expected to cause excessive collateral damage. Generally, the greater the risk in this regard in any particular context, the higher the level of command authorisation required. Figure 1 below shows this relationship.

Related to this is the impact of the passage of time. Generally, the greater the risk of harm, the greater the requirement for more immediate command authorisation. The duration of autonomous function must be limited within parameters which keeps the level of risk below the ‘reasonable foreseeability’ threshold. The duration of appropriate autonomous function in the environment in question will depend on the specific capabilities and limitations of the weapon or weapons system in question, as well as military necessity.

APPENDIX

Military autonomous aircraft pre-flight checks and authorisation

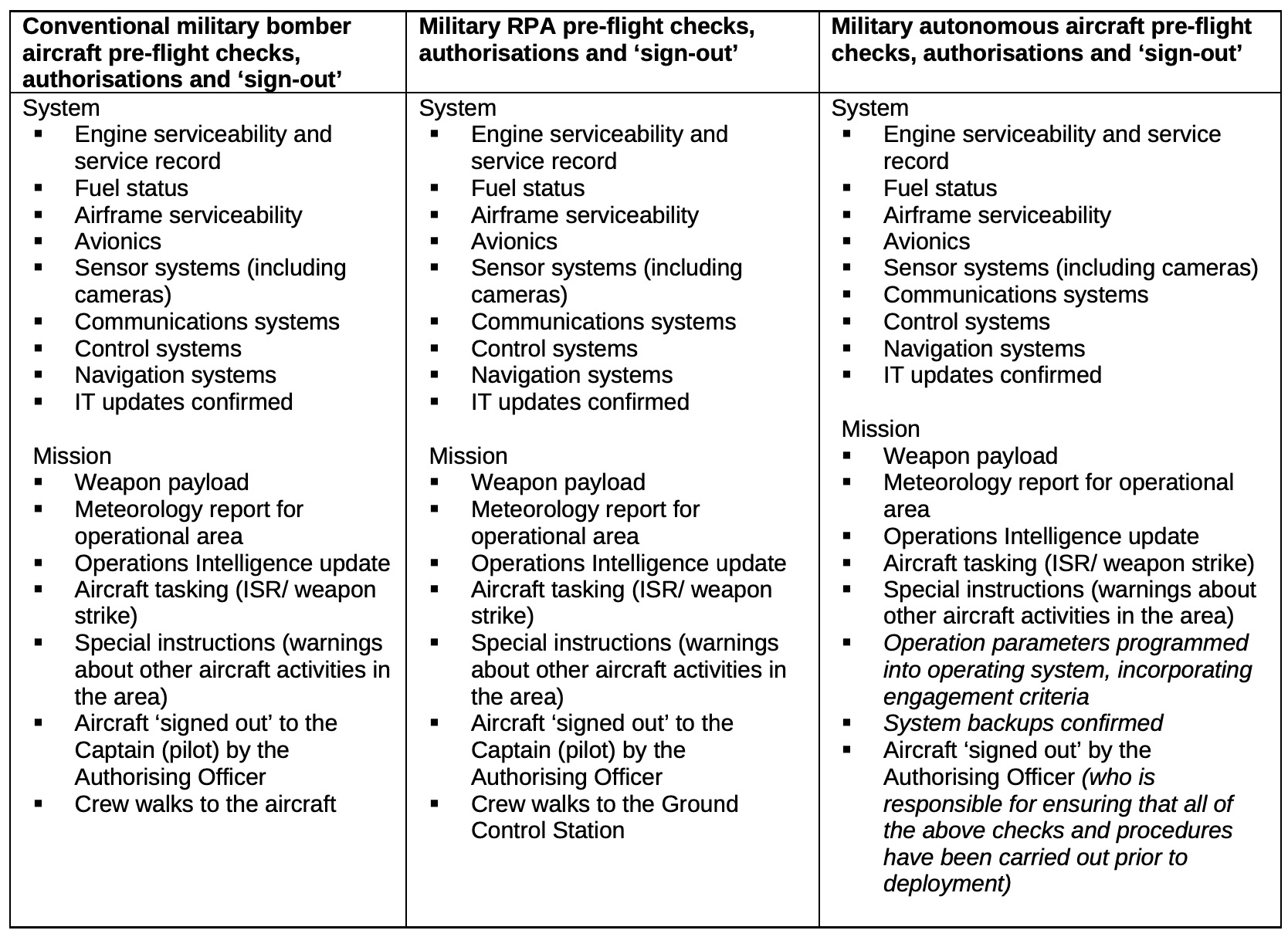

The employment of LAWS is conceptualised here by showing the continuity in system reliance and control measures between conventional bomber aircraft and remotely piloted aircraft (RPA). From this starting point the practicalities are set out to show how a future variant might operate when elements of its functionality are autonomous.

The following table sets out key elements of the pre-flight checks conducted prior to a typical mission by a military bomber aircraft (left column). Parallel principles and authorisations are shown for a military remotely piloted aircraft (centre column), then extended to set out the anticipated checks for an autonomous variant of the same aircraft. It illustrates the processes employed to ensure reasonable foreseeability of system safety and mission effectiveness. Several states that operate conventional and RPA use the same control procedures for both. While we do not yet know the specific requirements for an autonomous variant, historical experience with the introduction of new technology indicates it is likely the essential system and mission checks will remain the same, with incremental modifications.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Introducing Guiding Principles for the Development and Use of Lethal Autonomous Weapon Systems

- A Critique of the Canberra Guiding Principles on Lethal Autonomous Weapon Systems

- Historical and Contemporary Reflections on Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems

- ‘Effective, Deployable, Accountable: Pick Two’: Regulating Lethal Autonomous Weapon Systems

- Known Unknowns: Covid-19 and Biological Warfare

- Hybrid Warfare and the Role Civilians Play