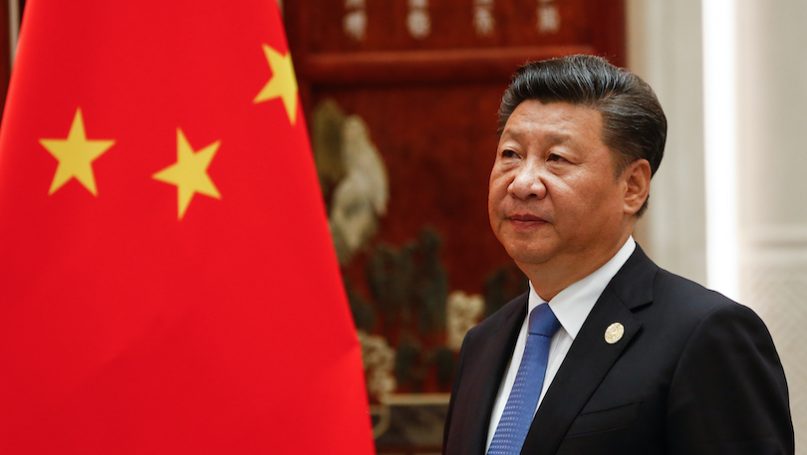

When Xi Jinping came to power, first as General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party and then as President of the People’s Republic of China, the space for Chinese civil society gradually shrunk. In the last few years, political power has sought new ways of imposing its influence on people; censorship has risen, mainly through the surveillance of media and internet as the virtual Great Firewall gets higher. In China today, there is no longer room for political satire: In 2017, the government even banned Winnie the Pooh from the web because it did not tolerate comparisons with President Xi. There is also no room for commenting on the decisions taken by Beijing’s government. The incrementation of the filtering, primarily on the internet, is also attested by the circulation of secret languages among Chinese users, who have substituted “sensitive” words with others that have not been censored yet in order to keep the political debate alive. For instance, some of them have created the hashtag #May35th to circumvent the censorship on the Tiananmen Square massacre and commemorate this tragic event, which the government would like to consign to oblivion.

In recent times, the Chinese leadership seems to be worried that the doctrine of “socialism with Chinese characteristics” is losing the capacity to bind people together with China’s ruling Communist Party. This has entailed making the Party’s doctrine attractive to people once again. Along with improving its persuasiveness, the Party has also felt the need to boost its control on civil society and avoid any deviations from its ideological dictate. Specifically, Xi Jinping chased a renewed authority of the Party in society by putting people at the core of political storytelling. He soon turned people into the protagonists of his narrative, by investing in them the historical mission of fulfilling the rejuvenation dream.

Thus, already in late 2012, Xi Jinping promoted the narrative of the “Chinese Dream”. This inspirational slogan revealed the Party’s intentions to provide a common aspiration for all Chinese people. The Chinese Dream can come true as long as everyone would contribute to its realization. For this reason, Xi Jinping has described his ambitious economic and political program as a people’s possibility for richness, or using the Chinese Dream’s vocabulary, a chance for “happiness”. In Xi’s narrative, indeed, wealth and happiness became synonyms.

This tendency was accentuated with the outbreak of COVID-19, when the Chinese government had to take charge of public health. The situation of emergency has made people more vulnerable given the uncertainty because of the development of the epidemic and fear of contracting the virus. The government’s necessary responses for containing the spread of the infection, also allowed the Party to hit the civil society at its heart and to condemn this to the immobilism. The lockdown, the closure of schools and universities as well as the ban on gatherings have restrained, at the same time, the circulation of virus and opinions. The pandemic provided a pretext for incrementing the government’s jurisdiction on society in order “to better protect people’s lives”. Taking care of people’s health, quickly resulted in heightened surveillance of individuals through the web and technology, like the development of apps for tracking movements during the quarantine or the diffusion of systems for facial recognition.

At this time, there is evidence that suggests that these technologies will be part of Chinese people’s everyday life, also even when the pandemic is over, as tools to maintain the interference of political power within society. Hence, the Party already declared how determined it is to face all long-term critical issues that are emerging due to the epidemic, such as the growth of unemployment and poverty, especially in most stricken provinces. During these last months, Xi Jinping released several statements in which he repeats how the government’s priority is that of “putting people first”. This centrality, that President Xi has always reserved for people, implies a reduction of the space of Chinese civil society.

Linguists – or, in general, social scientists who conduct scientific researches on the functions of language – teach us that when we talk, we correlate words with their ideational representations, consequently labelling and objectifying the reality that language contributes to shaping. Therefore, when the political power appropriates the use of a word, it could induce distortions of the meaning and perceptions that this term has conveyed so far. Deliberate and improper repetition of some words so provoke manipulations of thought. Likewise, when President Xi recurrently quotes the word “people” and sets this in his narrative, he is also altering the meaning of the concept “people” and making this available for his consumption.

Furthermore, Xi Jinping has proven to be a great story-maker. His evocative language favours the distribution of collective imaginaries, which he nurtures by speaking in parables: telling alleged memories of his childhood, symbolic stories of other people, or ancient legends that enrich his official speeches. Whenever people are displayed as the protagonists of his tales, however, they lose their autonomy, becoming functional to the transmission of a political message that aims at controlling them. Relatedly, now Xi Jinping affirms that China will defeat the COVID-19 diffusion by fighting a “people’s war against the epidemic”. This one of the most common and suggestive catchphrases that Xi Jinping has recently summoned speaking about the pandemic.

The just-one-person leadership of Xi Jinping, in a country already ruled by one-single Party regime, is converting language’s exploitation to match with political power’s ambitions, in a tangible risk for society. Plus, the hard government’s reactions to the protests in Hong Kong hint at how the Party is seriously concerned about the potential outbreak of social unrest in other regions of the country, which it is resolute to prevent by all means. As proof of that, censorship and surveillance are escalating dramatically.

However, for a great economic power like China, which no longer wants to be the factory of the world, such constraints on people’s capacity of thought could be a misstep towards a real rejuvenation of the country. Without the possibility to independently think and freely express, that allows us to question the reality around us, there are no ideas and there is no creativity. If China wants to pursue a power improvement of a qualitative type, will this be an obedient society helping to realize this aim?

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Rebranding China’s Global Role: Xi Jinping at the World Economic Forum

- Opinion – Factors Giving Rise to Xi Coup Rumours in China

- Xi Jinping’s Landmark Speech on Taiwan: A Hedging Strategy

- Opinion – Former China-Premier Wen Jiabao’s Censored Essay

- Opinion – Reconciling China’s Zero-Covid Policy with History

- Opinion – Taiwan Could Be to China What Canada Is to the US