Most countries, if not all, believe international recognition matters. International recognition represents status, which is directly determined and shaped by power – a combination of material attributes (i.e. wealth, weapons) and soft power. As such, it is reasonable to expect powerful countries to occupy top positions in the global status hierarchy. The more powerful a country is or is becoming, the higher the status it possesses or will be entitled to. While this general statement is not without theoretical support or empirical evidence, it nevertheless has generated puzzles and hence should be questioned. For instance, it has been widely argued that emerging countries, despite having gained tremendous material power capabilities, often struggle to obtain international recognition and desirable status as compared to the OECD countries. Why do some rich and powerful countries face more obstacles in claiming higher international status than others?

One such explanation in the existing IR scholarship on status is the ‘status glass ceiling’ argument, which claims that the existing international structure generates obstacles that have prevented emerging, ambitious status seekers from challenging the status quo (Ward, 2017; Pu, 2017). From this perspective, status in the form of international recognition can be seen as a scarce resource. A common belief held by scholars and policy makers is that a state giving recognition to another state can be self-defeating because it would ultimately undermine its own status position (Wohlforth, 2014; Mercer, 2017). Certainly, international environment can be extremely cruel and unfriendly, especially for rising powers which seek to break the status glass ceiling. However, studies have also shown that endogenous factors, as opposed to exogenous factors, tend to play a greater role in affecting the process of status seeking by a state (Pu, 2019).

On the other hand, a more prevalent view argues that rising powers often fail to gain positive international recognition due to the lack of soft power. Practitioners, especially, opt for the concept of soft power, and use it to identify rising powers’ strengths and weaknesses. The soft power argument appears to be a common understanding adopted by many scholars and policymakers to explain the lack of international reputation of some countries (Nye, 2004; Berenskoetter and Williams, 2007; Kurlantzick, 2007; Johnston, 2014). Rising powers are required to ‘prove’ to the rest of the world that they represent a model to emulate (Shambaugh, 2014). What exactly is preventing rising powers like China from gaining international reputation and recognition? In his 2014 Brookings Op-ed article The Illusion of Chinese Power, Shambaugh (2014) argues that “when China’s capabilities are carefully examined, they are not so strong. Many indicators are quantitatively impressive, but they are not qualitatively so. It is the lack of qualitative power that translates into China’s lack of real influence.” The ‘soft power’ argument provides a plausible explanation for the distribution of international status in world politics today. Established great powers such as the OECD countries tend to enjoy positive international recognition, and hence higher international status than less powerful status seekers (i.e. BRICs or other emerging powers).

Undoubtedly, the soft power argument is a convenient diplomatic vocabulary and intellectual shortcut for the understanding of the factors that have prevented some rich and materially powerful countries from becoming respectable great powers or ‘developed nations’. However, the concept of soft power is far too general and vague. When it comes to explaining political issues concerning the development of international politics such as status-seeking practices by states, soft power is not specific or precise enough to capture the dynamics which are crucial for the analysis. In particular, soft power can be highly subjective. This is most evident from the way the concept has been operationalized. In the annual Soft Power 30 report published by UK’s Portland Communications, which is considered the most comprehensive quantitative analysis of countries’ soft power, soft power is measured based on subjective indicators obtained from population surveys and interviewees’ personal views on their countries’ foreign policies. When it comes to empirical applications, the analytical limitations of soft power is also evident. Barr (2012) shows that existing works on Chinese soft power, for instance, often conflate hard power with soft power and in doing so mischaracterize China’s soft power. Thus, we aim to offer a conceptual framework that delivers clearer explanations for the status gap between the OECD and emerging countries.

Return of Nationality

We argue that a country’s status needs to be reconceptualized on a per capita basis, a concept we call “return to nationality”. We define “return to nationality” as the level of individual utilities – or to use a simpler term, satisfaction – derived from the net benefits and social welfare that ordinary citizens in possession of a nationality are entitle to. We argue that states attempting to claim higher status need to match their status claims with higher per capita returns to nationality. Putting forward return to nationality as the key to understanding the differences be tween the status concerns of the established great powers such as the OECD countries and that of the rising powers, this article addresses some pressing issues in world politics today. While traditionally states pursue international status by spending more on ‘visible’ status attributes such as expensive weapons or holding prestigious international events such as the Olympics sports competitions, they have less incentive to invest in the less ‘visible’ activities that would benefit the ordinary masses instead. This is precisely what this article seeks to challenge. The overarching message of this article is that status seeking countries should pay more attention to individual utilities – which is a function of the net benefits that an individual citizen is entitled to – by investing more in its social welfare system.

Capitalizing on the insights offered by authors like Shambaugh, we conceptualize the “lack of qualitative power” as “low return to nationality”, which could undermine the legitimacy of a state’s status claim both domestically and internationally. In our conceptualization, we treat nationality – broadly defined as citizenship or residency right of a country – as a form of capital that generates returns to individuals in possession of this capital. Return to nationality in this sense can be defined as the utility derived from a set of gains an individual in possession of a particular nationality is entitled to that is excludable to individuals not in possession of that nationality. This set includes but are not limited to access to free or subsidized education and health care services, pension payment and international mobility such as visa-free entries to other countries. Although things like universal free education are often seen as public goods domestically, they are no longer public goods when individuals of different nationalities are compared to each other because these provisions by definition are excludable to individuals not in possession of a nationality. While most countries provide their nationals with some kind of benefits like these, the quality of these provisions differ from one country to another, leading to vast cross-country differentials in the level of utility nationals derive from the benefits they are entitled to.

Our conception of “return to nationality” echoes some of the most commonly accepted approaches in contemporary academic research, especially in the field of political economy and development studies. The Human Development Index (HDI), for instance, can be taken as a reflective measure of return to nationality. The dimensions used in constructing the HDI, namely long and healthy life, knowledge and a decent standard of living are precisely the outcomes of health care, education, pensions and etc provided by national governments. The United Nations Development Program (UNDP) explicitly states that the HDI “can be used to question national policy choices”, and contrasts across countries in these outcomes “can stimulate debate about government policy priorities” (Human Development Index (HDI)). Similarly, there are several rankings of the powers of passports in terms of visa-free entries to other countries, such as the Global Passport Power Rank. These indices and rankings are direct measures of the level of international mobility enjoyed by the nationals of a particular country. To some extent at least, they also reflect foreign policy priorities of national governments in conducting diplomacy. In addition to the empirical measures, there is a body of theory-driven scholarship on the politics of welfare policies, especially of the developing world in the context of globalization (Burgoon, 2001; Rudra, 2002; Nooruddin and Rudra, 2014). Although the existing literature highlights the differences in the strategies and approaches adopted by developed and developing countries in welfare provision, it puts the demands of labor (the critical masses) at the center of the analysis and contends that both developed and developing countries behave similarly in this very sense (Nooruddin and Rudra, 2014). Furthermore, the above mentioned works treat the provision of welfare and social safety net as a policy variable, something controlled by and can be attributed to the national governments. The provision of social welfare and safety net, as we will demonstrate next, affects return to nationality.

The implication here is that since return to nationality represents the demands of the masses and its outcome depends on government policy and effort, it is an important part of international recognition. The recognition of a country’s status claims does not happen automatically when a country becomes richer or more developed. As noted by the UNDP, two countries with the same level of GNI per capita can end up with different human development outcomes. Simply being big (overall economic size) or even more developed (per capita income) does not guarantee higher expected utility of the nationals derived from their citizenship entitlements because greater material capability does not automatically bring about a more people and welfare-oriented policy agenda. When return to nationality is not significantly raised, claim of higher international status based solely on a country’s overall material capability or even per capita GDP could well go beyond the imaginations of the everyday citizens and therefore lack legitimacy. As far as legitimation is concerned, an extra effort on the part of the state is always needed to bring about a higher return to nationality. The legitimation of status claims – in practical terms – involves a transformation of higher GDP or GDP per capita to outcomes such as better social welfare, greater international mobility and cleaner environment that are more perceivable at the individual level and more attributable to the national government.

The Status Gap: OECDs vs BRICS

To further explicating our conceptualization of international status, we now illustrate our argument using the Composite Index of National Capability (CINC) score, and show why equating aggregate material power to status is problematic. The CINC score from the National Material Capabilities (NMC) Database (Greig and Enterline, 2017) is probably the most widely accepted and applied empirical indicators of international status up-to-date. It combines six industrial, military and demographic indicators – military personnel, military expenditures, total population, urban population, steel production and primary energy consumption – into a single index for each state year. A CINC value of 0 indicates that a state has 0% of the total material capabilities present in the system in a particular year. A value of 1 indicates that the state has 100% of the capabilities in a given year. The United States, for example, has a CINC score of 0.146 in year 2009, indicating that the US had 14.6% of the world’s total material capacities based on the six components in 2009.

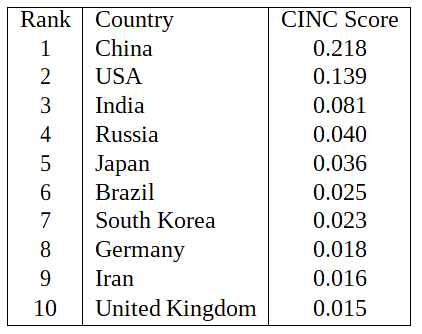

Thus, the CINC measurement scheme well reflects the conventional definition of status as “a state’s ranking on attributes, especially material attributes like wealth and military capability” (Duque, 2018, p. 578). According to the CINC score, countries with the highest international status include China, USA, India, Russia and Japan. Table 1 lists the top 10 countries with the highest CINC scores in year 2012. Clearly, the CINC score is state-centric, and focuses exclusively on material power attributes. The problem of using only material attributes to measure a country’s international status is rather obvious because countries like China, India, and Russia to some extent, are in fact struggling to obtain status recognition from other established great powers (Ward, 2017; Renshon, 2017). Thus, the main problem of the CINC score is that it puts status claimers like China, India, and Russia in the same category as status possessors like the US, Japan and Germany, which have established high international status and recognition. In contrast, our reconceptualization of international status based on return to nationality is able to effectively distinguish status claimers and status possessors.

There are broadly two types of “high-status” countries as measured by the CINC score, namely industrialized democracies such as the United States, and the emerging market countries represented by the BRICS. In fact, four of the five BRICS countries (China, India, Russia and Brazil) appear in the top10 list of the 2012 CINC score, together with a few industrialized democracies including the USA, Japan, Germany and the UK. While the two groups of countries are comparable in terms of their overall material capabilities, they differ tremendously in terms of per capita income and return to nationality. According to a report by the Center for Study of Governance Innovation, the BRICS is nothing but a “GDP Club”, which have adopted a development paradigm based on intensive extraction of natural resources, which drive most of their exports, and cheap labor, and have pursued GDP growth with little or no investment in human development.

According to the 2012 Human Development Index, Germany ranks the 4th in human development, followed by the USA (8th), UK (19th) and Japan (20th). None of the four BRICS countries, however, made it to the top 50 list. Russia, the highest of the four countries in human development, ranks the 52nd, followed by Brazil (86th), China (93rd) and India (131st). The above comparison shows that the BRICS countries, despite being big, fall behind the industrialized democracies in both development and return to nationality. In this sense, countries like Germany and the US possess more legitimized international status than the BRICS. Importantly, the HDI ranking reflects not only material well-being, but also return to nationality in the form of social support.

According to a New York Times article, countries like China do not have a functioning primary health care system. China has one general practitioner for every 6,666 people, compared with the international standard of one for every 1,500 to 2,000 people, according to the World Health Organization (Wee, 2018). It is therefore not surprising that people are often frustrated due to insufficient medical resources per patient, with some resorting to violence. As the same New York Times report shows, at tacks on doctors have become common in China and such phenomena are known as “medical disturbances” (Wee, 2018). Although China has impressed the world by its pace of economic growth, its return to nationality has not kept up with the country’s growth achievements at least for the time being.

Today, international status has become a key political concern for many countries partly due to the ongoing global power transition. As the perception of the ‘Decline of the West, Rise of the Rest’ is getting more prevalent, the ‘rest’, which mainly consists of the new rising powers, is believed to have threatened the status of the established western powers (Zakaria, 2008). There is an increasing concern, especially amongst western countries, that the rising powers would eventually replace them by seeking a higher status position within the social hierarchy (Wehner, 2017). Following the conventional state-centric understandings of status, having such concerns is perfectly understandable for the West. The change of the distribution of power could very likely lead to a change in the distribution of status internationally. Thus, as rational actors, the established greater powers have the incentive to minimize the possibility of losing their current status to the rising powers. The structural constraints imposed by the established great powers therefore have made the status glass ceiling even more difficult to break for the emerging powers (Ward, 2017).

However, as recent literature on status has argued, status recognition does not just come from without, but also from within (Pouliot, 2016). Introducing individual-level recognition into the analysis is necessary for one to grasp the larger picture of the distribution of international status. We further suggest that the distribution of status in the world politics today is not directly affected by the shift of the distribution of material power. While the balance of power might have shifted Eastward to some extent, the status hierarchy remains largely intact. The notion of the “rise of the rest” is to be questioned because as far as status competition is concerned, the “decline of the West” does not have much real content. As Zarakol (2019) points out, the ‘rise of the rest’ in Western policy circles had little relation to an objective reality and was more akin to a financial bubble. The debates and concerns about rising powers are manifestations of American/Western anxieties rather than an actual shift in the global power structure. The reality is that established Western powers have been and will be enjoying higher international status than the rising powers. One of the reasons for that, as we have explained in this article, is because they seek and maintain international status and recognition via sustainable means.

Table 1: Countries with the Highest CINC Scores in 2012

Conclusion

A state cares about its status, just like an average person cares about his or her well-being. Collectively, the critical masses demand a higher return to nationality, which is a critical step for any modern nation-state to obtain and sustain legitimacy domestically and internationally. If a country struggles to gain international recognition, the international environment is not to be blamed solely as domestic policy priorities and achievements also play a role in shaping international recognition and conferment of status. If a rising power truly cares its international stand and reputation, the optimal status seeking strategy in the long run is to invest in the overall well-being of its people.

Although concepts like status are conventionally defined of the state and for the state, individual perceptions and responses to these state-level games and rhetoric in the context of global flow of information and people carry not only attitudinal but also behavioral consequences. By conceptualizing status on a per capita basis, we echo the long established tradition in social sciences to use per capita outcomes as measures of individual well-being (Young, 2005) and mechanistically connect individuals to states and international affairs. In democracies and even authoritarian regimes, state-level games such as status claim almost always involve everyday people to some extent. Understanding the material gains, symbolic attachments, political underpinnings and social meanings of international status in the eyes of individuals sheds light on not only discussions of status, but also broader themes such as nationalism and migration in world politics today.

References

Barr, Doctor Michael (2012). Who’s afraid of China?: The Challenge of Chinese soft power. Zed Books Ltd.

Berenskoetter, Felix and Michael J. Williams (2007). Power in World Politics. New York: Routledge.

Burgoon, Brian (2001). “Globalization and welfare Compensation: Disentangling the Ties that Bind”. In: International Organization 55 (3), pp. 509–551.

Duque, Marina G. (2018). “Recognizing International Status: A Relational Approach”. In: International Studies Quarterly 62 (3), pp. 577–592.

Greig, J Michael and Andrew J Enterline (2017). “National Material Capabilities (NMC) Data Documentation Version 5.0”. In: Correlates of War 27.

Johnston, Alastair Iain (2014). Social States: China in International Institutions, 1980-2000. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Kurlantzick, Joshua (2007). Charm Offensive: How China’s Soft Power Is Transforming the World. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Mercer, Jonathan (2017). “The Illusion of International Prestige”. In: International Security 41 (4), pp. 133–168.

Nooruddin, Irfan and Nita Rudra (2014). “Are Developing Countries Really Defying the Embedded Liberalism Compact?” In: World Politics 66 (4), pp. 603–640.

Nye, Joseph S. Jr (2004). Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics. New York: Public Affairs.

Pouliot, Vincent (2016). “Hierarchy in Practice: Multilateral Diplomacy and the Governance of International Security”. In: European Journal of International Security 1 (1), pp. 5–26.

Pu, Xiaoyu (2017). “Ambivalent Accommodation: Status Signalling of a Rising India and China’s Response”. In: International Affairs 93 (1), pp. 147–163.

Pu, Xiaoyu (2019). Rebranding China: Contested Status Signaling in the Changing Global Order. Redwood City: Stanford University Press.

Renshon, Jonathan (2017). Fighting for Status: Hierarchy and Conflict in World Politics. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Rudra, Nita (2002). “Globalization and the Decline of the Welfare State in Less Developed Countries”. In: International Organization 56 (2), pp. 411–445.

Shambaugh, David (2014). The Illusion of Chinese Power. URL: https://www.brookings. edu/opinions/the-illusion-of-chinese-power/ (visited on 06/25/2014).

UNDP. Human Development Index (HDI). Accessed on November 13, 2019. URL: \url{http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-index-hdi}.

Ward, Steven (2017). Status and the Challenge of Rising Powers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wee, Sui-Lee (2018). China’s Health Care Crisis: Lines Before Dawn,Violence and ‘No Trust’. URL: https:// www. nytimes. com/ 2018 / 09 / 30 / business/ china- health- care- doctors.html (visited on 09/30/2018).

Wehner, Leslie (2017). “Emerging Powers in Foreign Policy”. In: Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics.

Wohlforth, William C. (2014). “Status Dilemmas and Interstate Conflict”. In: Status in World Politics. Ed. by T.V. Paul, Deborah Welch Larson, and William C. Wohlforth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 115–140.

Young, Alwyn (2005). “The Gift of the Dying: The Tragedy of AIDS and the Welfare of Future African Generations”. In: The Quarterly Journal of Economics 120 (2), pp. 423–466.

Zakaria, Fareed (2008). The Rise Of The Rest: The Post-American World. Newsweek.

Zarakol, Ayşe (2019). “‘Rise of the Rest’: As Hype and Reality”. In: InternationalRelations33 (2), pp. 213–228.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- India-China Rivalry and its Long Shadow Over the BRICS

- Adding ‘T’ to BRICS: A NATO Ally in Transition

- Forty Years of Constructing Development: How China Adopted GDP Measurement

- Opinion – Challenges for the Expansion of the BRICS

- The Internationalization of the Chinese Renminbi: Firm Steps, But a Long Road Ahead

- Student Mobility and Its Relevance to International Relations Theory