In my article The food crisis: its causes and consequences [1] published on this site I proposed a theoretical model of development. A very important tenet of the model is the correspondence of the society’s political organization to the population’s level of development. Hence countries of approximately the same level of development must have similar social organization. The main problem is to definite a criterion of the level of development. According to the theory, the more complicated people’s labour activity, the higher their level of development. Throughout history, the labour activity of a population has become more and more complicated. The most primitive form of labour are hunting and gathering. Next came nomadic cattle breeding, forest-follow systems and other forms of shifting cultivation. Genuine agriculture begins only with two-fields and three-fields rotations systems. The more intensive stages of agriculture are horticulture, viticulture and vegetable-growing, especially in greenhouses. Rice plantations are particularly labour-intensive. Here I must to note a common mistake of English-speaking mass-media. Usually all agriculturists are called “farmers”, maybe because the English peasantry (yeomanry) disappeared as long ago as the 18th Century. But there is great difference between agriculturists, who produce agricultural production for their own consumption, and agricultudirists who work to market their product. The former practice subsistence agriculture and must be called “peasants”, while the latter are farmers. The labour activity of farmers is much more complicated

Non-agricultural labour usually is more complicated than any agricultural labour. The most primitive forms of non-agricultural labour are mining, retail trade, building industry, transport and some others. Here the question is the labour of blue-collar workers, not the labour of designers and architects. The former type of labour, such as machine-building, is much more complicated. Next follows the labour of white-collar workers: civil servants, labour in engineering, finance and banking, education, science.

Certainly the most important criterion is the share of agricultural labour force in total labour force, because the transition from a pre-industrial society to an industrial one is a result of the transition of the agricultural labour force to non-agricultural sectors of the economy. But the share cannot be defined exactly, because of part-time work. Therefore different sources give very different figures. Hence the criterion is absolutely valid only when the share of agricultural labour of different countries differs considerably, for example 80%, 30% or 10%. If the difference is not so salient, other factors may be of importance.

Interesting example of such factors are provided by the political situation in the countries of the former Soviet Union. All these countries may be divided in four groups: the states of Central Asia, the states of the Caucasus, the Baltic states and the Slavic states.

The share of agricultural labour force in Central Asian states is between 20-30% except for Kazakhstan. All countries with an index of democracy less than 4 are defined by the Economist Intelligence Unit as having authoritarian regimes, with a score between 4 and 6 indicating hybrid regimes, between 6 and 8 counting as flawed democracies, and 8-10 ranking as full democracies. From all Central Asia post-soviet countries only Kyrgyzstan has an index of more than 4. But before 2005, the country was under the authoritarian regime of Akayev. In 2005 the so-called tulip revolution occured and Akayev’s regime was toppled.

The proposed model defines two types of revolution. The first one is genuine or peasants’ revolution caused by the filling up of the reservoir for the last time. This type of revolution may occur only in countries where peasantry consist of the majority of the population (50-90%). The peasants’ revolution always has as a result a decline in the economy, numerous deaths, and the establishment of authoritarian regimes. The peasants’ revolution may take forms very different from our image of revolution.

Another type of revolution which may be called a colour revolution occurs in countries where peasants’ revolutions have occurred and an authoritarian regime was established. The colour revolution may occur in a society where agricultural labour force consists from 10% to 40% of the total labour force. The underpinning forces of colour revolutions are very different. The most active but smaller group consists of the most educated classes of society – students, white-collar workers. The second group is the most backward stratum: peasantry and unskilled workers who came to towns from villages. The first group wants economic and political liberties, because they want and can make their fortune. The second group wants to raise its standard of living by political means. According to the proposed model, it is impossible because the standards of living could only rise in conjunction with the level of development. The different aims of driving forces of the colour revolution determine its results. Usually, at first the aims of the first group are reached: the authoritarian regime is toppled, the mass-media and economies are freed. But the second and the largest group is not satisfied. They want the government to interfere in the economy with egalitarian actions: price control, redistribution of agricultural land, payment of allowances and increase of wages. So the results of the colour revolution depend on a struggle between its main driving forces. Therefore the political situation in the country becomes unstable for a long time. If the share of agricultural labour is high (30-40%), second and third colour revolutions may occur.

After colour revolutions a genuine democracy is impossible because of the still low level of the population’s development. It is a populist democracy when the people vote for politicians who promise to raise the standards of living. In such countries, inflation is usually high because the politicians print money in great amounts to fulfill their promises.

Hence, according to the proposed model, in 2005 a colour revolution took place in the Kyrgyz Republic. The unrest began in backward and poor south and south-west Kyrgyzstan. During the next five years, the political situation in the country was unstable and in 2010 a new colour revolution happened. So, according to the theory, in Kyrgyzstan the post-revolution period has resulted in the mass-media being mainly free and real political liberties. But the common level of development is relatively low, therefore the situation in the country may change considerably, and upsetting of social organization is probable.

In contrast to Kyrgyzstan, in Kazakhstan the share of agricultural labour is low enough for transition to democracy. But Kazakhstan has an abundant supply of accessible mineral and fossil fuel resources. For example, Kazakhstan is the largest world exporter of uranium and by 2015 may be among the top 10 oil-producing nations in the world. Therefore, the government of the country can provide the population with relatively high living conditions so the broad masses of society back the Nazarbayev regime. Besides, in Kazakhstan the share of mining in industry is great while agriculture is very extensive (mostly cereal cultivation and cattle-grazing) so that the real level of development is lower in relation to the share of agricultural labour.

The lowest level of development in post-soviet Central Asia is in Turkmenistan, corresponding to the lowest index of democracy. The country possesses the world’s fourth-largest reserves of natural gas and substantial oil resources. As in Kazakhstan, it allows the regime to remain in power. In Tajikistan, the level of development is very low too and it is the poorest country in the region. In Uzbekistan the level of development is somewhat higher but it is insufficient for transition to democracy, even its populist form without violence.

As a whole the situation in the Central Asian region is fraught with future social disturbances. They are inevitable in all countries but the degree of violence will be different according to the achieved level of development. The bloodiest events are possible in Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan. In the latter country, a variant of the Libyan example is quite probable. In the Kyrgyz Republic, the transition to a populist democracy has begun though some outbreaks of violence are possible. It is very probable that in Kazakhstan the transition to democracy will be relatively peaceful. For such transition the share of educated people must increase while the economic situation in the country must worsen. Such conditions may occur during the next economic crisis. The next group of post-soviet countries are in the Caucasus.

Table 2

The share of the agricultural labour force in Azerbaijan corresponds to the index of democracy. The great oil and gas exports create considerable possibilities for the authoritarian regime of Aliyev to remain in power. For Armenia, the index is somewhat lower and for Georgia it is somewhat higher corresponding to shares of agricultural labour. The growth of Georgia’s index of democracy resulted in the colour revolution of 2003 (the so-called Rose revolution), as it did in Kyrgyzstan. Besides, Georgian agriculture is very intensive. For the foreseeable future, the most stable political situation will be in Armenia; some disturbances without violence are possible in Georgia. For Azerbaijan a colour revolution is inevitable. It is possible that it will begin during future economic crises when oil prices fall. The high share of agricultural labour increases the probability of violence during the revolution.

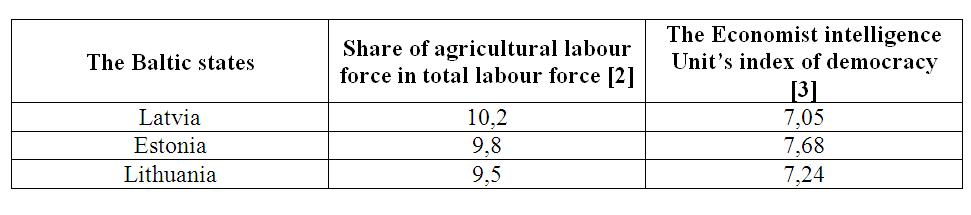

In the Baltic States the shares of agricultural labour and democracy index are practically the same. As a whole the share of agricultural labour in the Baltic states is higher than in most countries of Western Europe (1.5-4%). But the share is sufficiently small to exclude subsistence agriculture. Therefore, in these states the standards of democracy are as high as for post-Soviet

Table 4

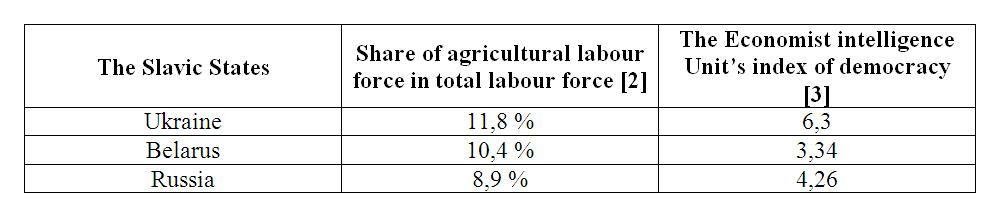

The Slavic post-soviet states give us the most controversial data. The shares of agricultural labour there are approximately the same as in Baltic states. But indices of democracy differ considerably. In Belarus, Lukashenko’s regime is authoritarian, in Russia the regime is considered as “hybrid regime”, while in Ukraine “flawed democracy” exists.

First of all I must say that figures of agricultural labour in post-soviet Slavic states do not correspond to the level of development of the population, because the natural process of social transformation there was distorted by the Soviet regime. After a genuine revolution, the peasantry would have gradually transited from agriculture to industry and trade, becoming workers in towns and farmers in villages. But in the Soviet Union the peasant’s land was confiscated by the state and the peasantry were turned into hired workers on state farms. These workers lacked any stimulus to work with assiduity; furthermore the managers of these farms were hired workers too. In industry and trade all were hired workers on state enterprises. The owner of all these enterprises was the state, that is nobody in particular. As a result, the labour of all Soviet people was not as complicated as it should be under natural conditions. Therefore, the structure of the employment of the Soviet population did not correspond to the achieved level of development.

In Central Asia and the Caucasus, the transition of peasants to industry and trade had begun much later than in Slavic Soviet republics and is not completed yet, therefore the distortion of the transformation of society was considerably smaller. The Baltic States were fully incorporated into the Soviet system only in the 1950s, when the transition of these states to industrial society had been completed, so the distortion there was minimal too.

The level of development of all Slavic states is the highest in Russia owing to Moscow’s population. In the Soviet Union, Moscow was a city with a privileged position. The government, countless scientists and cultural institutions were located there. Many people who were prominent in their trade came to Moscow from all over the Soviet Union. The population of the old capital, Saint Petersburg (Leningrad) also has a relatively high level of development. But in Russia the political situation is influenced by the wounded imperial complex of Russians. Notwithstanding assertions of Soviet authorities that, in the USSR, all nations were equal, the country was perceived by population as a country of Russians because the capital was in Moscow. The state language was also Russian and the majority of the population consisted of Russians. Other nations were Russified and everybody who wanted to make their way up had to speak Russian and adopt Russian culture. Notwithstanding the fact that the overthrow of the communist regime was a Russian colour revolution, the further dissolution of the USSR was understood by Russians as tearing away parts of the Russian state, first and foremost by the western alliance NATO. The majority of Russians consider NATO as a hostile power which plans the further destruction of the Russian state. All attempts of other nations with Russia to obtain their independence were perceived by many Russians as incited by NATO. Therefore they think that Russia needs strong hands at its centre to stop the attempts at secession. The failures in the Chechen wars were especially painful for Russians. Even the Russian liberal intelligentsia, which was the main driving force of the colour revolution of 1989-1991, wanted the consolidation of state power. So the coming of Putin to power was greeted with enthusiasm.

To what extent did the wounded imperial complex of Russians reinforce Putin’s regime? This is a difficult question to answer, but it is beyond doubt that it did. Notwithstanding, today’s regime in Russia is considered a “hybrid” one, that is not authoritarian. In Belarus the regime of Lukashenko is authoritarian and in Belarus there is no imperial complex. Hence, the index of democracy corresponds to the level of development of the Belarusian population. The most interesting situation is in Ukraine. The index of democracy there is the highest of all post-Soviet countries, except for the Baltic States. I must note that in all countries where colour revolutions happened, the indices of democracy are above the correspondent level of development. So it was in Kyrgyzstan, Georgia and Ukraine. After the “orange” revolution in 2004, the Ukrainian index of democracy rose even higher. The Economist Intelligence Unit determined that index, in 2006, to be around 6.94. Later, the process of correction began and standards of political life are approaching the achieved level of development. Nevertheless, in Ukraine the index is too high. The cause of the phenomena is an interesting example of the action of casual factors which were mentioned at the beginning of the article.

The territory of Ukraine is divided in forest zone and steppe zone. The first one is the historical core of Ukrainian lands, the second one had been a land of nomads and was occupied by agriculturists only between the18 th -19th Centuries. Migrations to the steppe zone had come not only from Ukraine but from Russia and, to a much lesser extent, from Balkans, Germany, Poland and some other countries. Owning to great deposits of iron ores in the Kryvyi Rih region, the rich coal fields of the Donets basin and manganese ores of Nikopol basin, the steppe zone of Ukraine became the fastest developing industrial region of the Russian empire and later of the USSR. Therefore, agricultural migration to the steppe zone was altered by industrial migration. As a result, the population of industrial regions of the steppe zone of Ukraine was Russified to a large extent. Now the Ukrainian population is divided in two halves—the Russian-speaking population of mainly industrial steppe zone (easterners) and Ukrainian-speaking population of mainly agricultural forest zone (westerners). Theses population groups differ not only in language and cultural traditions but in levels of development, because industry in the East is much more developed. Differences between the two halves of the Ukrainian population cause different political preferences. Therefore in Ukraine there are usually two political parties or two political leaders, one of them being more supported in the West and another in the East. By chance, the votes of westerners and easterners are roughly equal. Though the level of development in both parts of the country is not high enough for democracy, no part of the country can establish its own authoritarian regime because the educated people with high level of development in the West as well as in the East vote against it. So by chance, the interests of both halves of population are balanced, while democracy ensures a balance of interests of all social groups in society. At the same time, there is evidence of a relatively low level of development in the Ukrainian population. For example, the index of economic freedom of Ukraine is one of the lowest in the word. The country’s rank is 164 out of 179. Ukraine’s freedom index is 45.8, which is considered “repressed”. From the post-soviet countries only Turkmenistan has a lower rank. [4]

Thus the social organization of society corresponds to level of development of the population. But after colour revolutions, the level of social organization may be above correspondent levels of development for some years. The share of the agricultural labour force of the total labour force may be used as criterion to measure a society’s level of development. At the same time, other factors may be of great importance and must be taken into account.

[2] Here and further I used data from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available on http://www.fao.org/economic/ess/ess-fs/ess-fs-country/en/

[3] http://www.eiu.com/public/

[4] http://www.freedomhouse.org/template.cfm?page=25&year=2010

http://www.heritage.org/index/ranking – economic liberties. 2011

Written by: Andrey Alexakha

Written at: Dnipropetrovsk University

Written for: Dr. Sviatets

Date written: 11 May 2011

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Gendered Implications of Neoliberal Development Policies in Guangdong Province

- Transnational Corporations, State Capacity and Development in Nigeria

- The Gouzenko Affair and the Development of Canadian Intelligence

- Development and Authoritarianism: China’s Political Culture and Economic Reforms

- Ripening Conflict in Civil Society Backchannels: The Malian Peace Process (1990–1997)

- Pluralist Diplomatic Relations: COVID-19 & the English School’s International Society