On 13 October 2020 the directors of NASA and seven other national space agencies signed the Artemis Accords, a document purporting to articulate international norms for the development of the Moon, Mars and other celestial objects of economic interest in the near future. International public opinion ignored the announcement and international elite opinion was underwhelmed. Yet, there are good reasons why so few outside the orbit of space policy experts took notice and many of those who did were unimpressed.

First, the directors of the space agencies of the principal competitors of the USA in space – rival China and semi-rival Russia – were not among the signatories. Instead the other seven included the directors of the second-tier and third-tier space faring powers UK, Japan, Australia, Canada, Italy and the U.A.E., and no-tier Luxembourg. This wasn’t even a complete list of the allies the USA can normally count on to support its diplomacy. Brazil, South Korea, Israel and Saudi Arabia are all aspiring space faring states and the signatures of the directors of their space agencies are missing, as is that of the fifth member of the Anglo-American ‘five eyes’ intelligence alliance: New Zealand. As an articulation of international norms, the Artemis Accords is largely uninhabited.

Second, although the first page of the document affirms “the importance of compliance” with the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, with the exception of the U.A.E., the signatures of the Global South’s space agency directors are missing. That matters because the treaty on which the international legal regime for space is based achieved its legitimacy only because it won acceptance not only from the United States and Soviet Union and their junior allies but also from countries in what was then described as the Third World.

While the superpowers signed the 1967 Outer Space Treaty as a nuclear arms control agreement for space, most of the rest of the planet signed because it offered an unambiguous prohibition of territorial annexation or national appropriation to assuage historical anxieties about imperialist rivalry in the heavens while also promising in rather ambiguous language that the scientific and economic benefits of space as an international commons would be shared internationally. The 1979 Moon Treaty, which explicitly promised that sharing the scientific and economic benefits from the resources of the “Eight Continent,” was strongly supported by the Global South but just as strongly opposed by the USA. That’s why today it a dead letter.

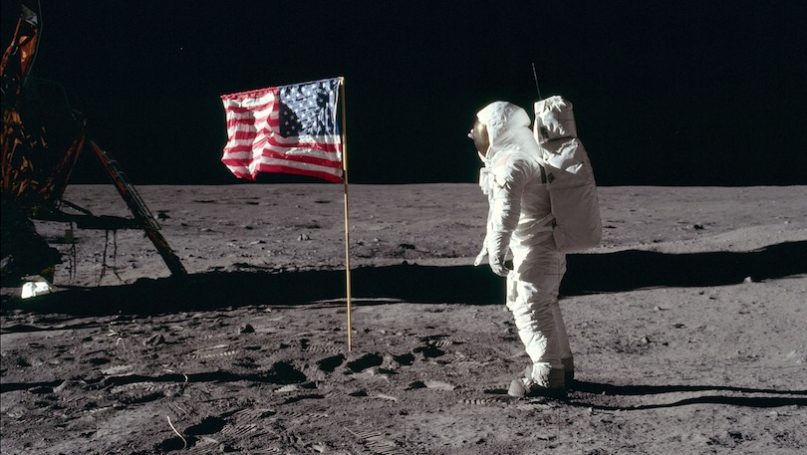

What the 1967 Outer Space Treaty failed to provide was the international legal basis for the sort of property rights that investors want when making hefty and risky investments like extraterrestrial mining operations. Yes, there are potentially highly profitable mining opportunities on the large object regularly visible in the night sky. The Moon is much closer than any other large celestial object and hidden beneath its Asia size area are minerals and water ice crucial for further space exploration and development.

The Artemis Accords are an international legal ‘work around’ to recognize and protect those exotic property rights while pretending that their assertion by the USA is not effectively the territorial annexation or resource appropriation clearly prohibited by the 1967 Outer Space Treaty. Section 10, Subsection 2 of the Artemis Accords references the “extraction and utilization of space resources, including recovery from the surface or surface of the Moon, Mars, comets or asteroids” and promises that “The Signatories affirm that the extraction of space resources does not inherently constitute national appropriation under Article II of the Outer Space Treaty.” That is the sort of language written by lawyers resigned to the reality that their work must fail the “duck test.”

Law often involves fiction, especially when it is deemed useful for facilitating commerce. The assumption that large business corporations and individual consumers are equally competent to negotiate the terms of contracts with one another is an example. So long as almost everyone plays along, such fictions may be reasonably functional. The problem with the Artemis Accords is that few countries appear willing to suspend disbelief. Absent signatures from space agency directors of China, Russia and the most of the Global South, the document is exposed as the first step in the annexation of territory or appropriation of resources on the Moon via condominium – the USA plus a small circle of its friends – in violation of the explicit prohibition in the 1967 Outer Space Treaty.

So the Artemis Accords are likely to be transient lunar phenomenon, of the political sort. The USA can get away with them only so long as it absorbs some of the business risk of the sketchy international legality extraterrestrial mining projects and crucially neither China nor Russia decide to renounce the 1967 Outer Space Treaty by annexing their own slices of lunar territory. That both Beijing and Moscow view territorial annexations rather differently than Washington is evident in the former’s claim over the South China Sea and the latter’s annexation of Crimea. Indeed, they might be tempted to poke holes in the fiction simply to take the USA down a notch. Ironically, over the long term, the only way to save the Artemis Accords from that fate would be to engage in the sharing of lunar resources with the Global South so vigorously opposed in the 1979 Moon Treaty.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – Getting Diversity ‘Right’ In Australia’s Nascent Space Industry Matters

- What’s Wrong with Outer Space Colonialism?

- Opinion – Breaking Boundaries to Reimagine Space is Crucial

- Opinion – What the US Exit from the Paris Accords Means for Women

- Opinion – China’s Saudi-Iran Deal and Omens for US Regional Influence

- The Final Frontier for the Faithful: Islamic Rulings on Space