This interview is part of a series of interviews with academics and practitioners at an early stage of their career. The interviews discuss current research and projects, as well as advice for other early career scholars.

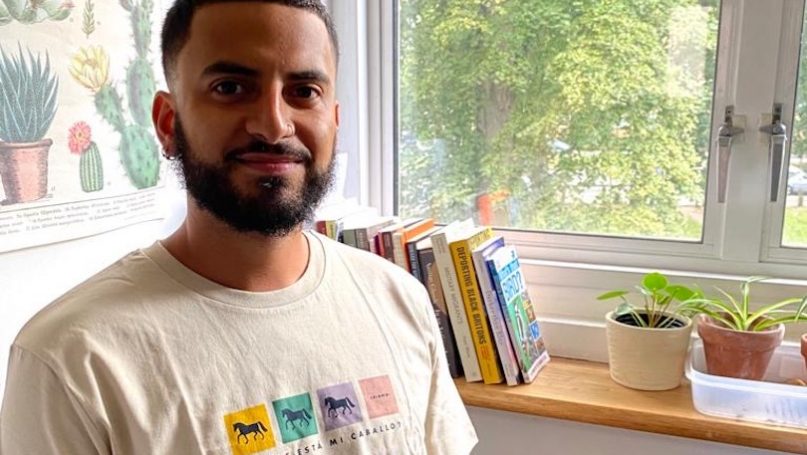

Luke de Noronha is an academic and writer working at the University of Manchester. He is the author of Deporting Black Britons: Portraits of Deportation to Jamaica, and producer of the podcast Deportation Discs. He has written widely on the politics of immigration, racism and deportation for the Guardian, Verso blogs, VICE, Red Pepper, openDemocracy, The New Humanist, and Ceasefire Magazine. He lives in London and is on Twitter @LukeEdeNoronha. (For 30% off Deporting Black Britons use the code ‘Deporting30’ on the MUP site).

What (or who) promoted the most significant shifts in your thinking or encouraged you to pursue your area of research?

In my time as an undergraduate I was most taken by the work of Stuart Hall and his many disciples. It was that body of writing on ‘race’, racism and identity, culture, belonging and difference that occupied my thinking. At the same time, I started working with people in the asylum system, making friends with people who lived under the constant threat of illegality, detention and deportation. Trying to bring these two perspectives on Britain into conversation has shaped my work since: the anti-racist position, which takes culture and identity (or, better, identification) seriously, and the perspective of the legally excluded, people racialised precisely through their ‘migrantness’ and ‘illegality’.

My decisions about what to research have been motivated by close attention to specific forms of border violence, and a deep concern with what that violence does to all of us. I have long been frustrated by liberal arguments about the deservingness of specific groups of ‘vulnerable’ migrants – genuine refugees, victims of trafficking, womenandchildren – and wanted to move away from arguments about innocence and victimhood (hence my focus on ‘foreign criminals’, those archetypal ‘bad migrants’). Of course, my critical perspective on borders and racism did not come to me in some of kind of vision, but rather through listening to people engaged in radical political movements against immigration controls, and indeed against prisons.

In your article Deportation, racism and multi-status Britain, you dispute the claim that the UK’s immigration regime is non-racist. As well as reflecting British racisms, how do immigration controls shape and produce racial meanings and racist practices?

The claim that immigration controls are ‘not racist’ is important for the states doing the bordering. After all, no one wants to be racist, not even far-right ultranationalists. But when political parties feel compelled to say ‘it’s not racist to worry about immigration’, they reveal something. Partly, of course, they are banging the ‘PC-gone-mad’ drum and summoning the ‘culture wars’ – making a kind of ‘these lefties will call anything and everything racist’ argument. But the fact that they have to keep saying that controlling immigration is not racist does remind us that issues surrounding ‘race’ and immigration cannot be held apart for very long. After all, the country’s racialised outsiders are ‘migrants’ – or at least originally they were, they are second generation or ‘of migrant background’ – and if they misbehave ‘they should go back to where they (really) come from’. Anti-immigrant discourse targets migrants defined in racial terms (Muslims, Arabs, Africans, Roma). Racial anxieties and resentments always concern matter out of place, outsiders in the national hearth, whether we made the mistake of letting them in yesterday or several generations ago, and racism is a measure of the will that expel, excise and expunge these foreign bodies.

So, immigration controls can never be raceless, and many migrant activists respond with the bold assertation that in fact borders are inherently racist. I agree with this broad claim, but I’m interested in what we mean by it. Sometimes people mean ‘borders are racist because they discriminate unevenly against groups within the system – e.g. black people more likely to be restrained during deportation flights’. More broadly, some make the argument that ‘borders are racist because most people detained and deported come from Britain’s former colonies’. The problem with the first argument is that it looks for evidence of discrimination and disproportionality to reveal the truth of racism, when in fact it is the legal classification, segregation and expulsion that in itself constitutes the racism (perhaps racism is the word that leads us astray here, and instead we should say that borders are technologies of racial governance, raciology, race-making, or something similarly unsightly). Meanwhile, the latter argument about racism and the formerly colonised, while more structural, is also unsatisfactory, not least because it’s not always true. The top three nationalities deported in 2017 were Albanian, Polish and Romanian, even if Indians were likely to be detained for longer, and Jamaicans more likely to be forced onto flights in body belts. The point is that immigration controls do not simply reflect racisms of old, replaying the same colonial story with different characters. Things change, in ways that matter.

Racism is historically specific, always in formation. As Cedric Robinson puts it (in this admittedly over-cited passage): “Race presents all the appearance of stability. History, however, compromises this fixity. Race is mercurial – deadly and slick” (2007: p. 4). As people concerned with challenging racism and defending people’s right to move around, we have to be alert to how movement and controls on movement produce and reconfigure racial distinctions and hierarchies in the present (even if they are not named in racial terms). Race-making is always centrally constituted by the government of mobility, and we need to make links between ostensibly race-neutral immigration and citizenship policies and cultures of racism and violence on the streets. I suppose most importantly, recognising that immigration controls shape and produce racial meanings and practices reminds us anti-racism necessarily means supporting (illegalised) migrants, and not allowing ourselves as minoritised citizens to feel settled in our provisional belonging while others are being detained and deported.

Your new book Deporting Black Britons: Portraits of Deportation to Jamaica tells the life stories of four men who grew up in the UK and were deported to Jamaica. What do these biographies tell us about immigration control and race in contemporary Britain?

The book uses life story and ethnographic methods to develop intimate portraits of these four men, men who moved to the UK as children and spent roughly half their lives in the UK before being deported to Jamaica. They grew up in the UK, identify with Britain, and they are indistinguishable from black British citizens, and yet now they live in Jamaica, in exile, separated from their partners, parents, children, etc. The book bears witness to their stories as a way of reminding readers just how cruel the UK’s immigration system is, and how these policies impact not only deported people but their loved ones who remain.

In the book, I argue that Britain is increasingly multi-status, so that divisions we are used to analysing – surrounding race, gender, class – are fractured and complicated by legal status. Immigration controls carve through friendship groups and intimate relationships, between siblings, parents and children, schoolmates, neighbours, colleagues and prisoners, creating new lines of division and exclusion. If we want to understand racism in Britain, we need to pay attention to this. But just as importantly, if we want to understand how immigration controls are actually enforced, then we need to think about the structuring force of racism in determining whose immigration status is most likely to be realised, ultimately in deportation. Not everyone who is deportable will be deported; racism is central to determining who actually gets removed. Most importantly for my work, people who are criminalised are among the most likely to face deportation, and therefore racism in the criminal justice system has deportation consequences.

More broadly, the book looks at when and how these four men were criminalised and illegalised, questioning how these processes were shaped by racism, poverty and gendered identities – making connections between the UK’s immigration regime and police racism, austerity, and masculinities. In doing so, hopefully the book offers portraits not only of these four men, but a portrait of Britain, a country which I argue is increasingly multi-status and multi-racist.

What were you able to learn about post-deportation life through your fieldwork in Jamaica?

Firstly, there’s the crushing brutality of deportation, which becomes so much sharper and more forceful when you spend time with people post-deportation. When you sit with someone, over time, and talk, and when everything pivots back, always, to the finality of deportation, the enforced separation and absence, the rupture and the devastation. Trying to write about that has been difficult, but it remains the main rationale for the book, my attempt to say something critical and meaningful about these stories.

Then of course, by spending time in Jamaica and meeting people after they had been deported, I was able to situate their experiences in relation to other Jamaicans struggling to find space to breathe. What is shared between deported people and those they return to live among? Asking this question raises several other questions about Jamaican economy and society, about the frustrated mobilities which characterise Jamaican citizenship more broadly, and about the ways in which histories of slavery and colonialism ‘eat into the present’ (to borrow a phrase from Stuart Hall). In the last two chapters of the book, I talk about mobility and race-making, citizenship in a global perspective and about Jamaican economy, society and history. I suppose this is a strength of moving between the UK and Jamaica in the research. Deportation can no longer remain solely a national policy question, which becomes especially clear when you realise that deportation is embedded within other foreign policy and diplomatic arrangements, most notably in terms of aid and development.

In your podcast Deportation Discs (a play on Desert Island Discs), ‘deportees’ in Jamaica tell their stories of exile through music. How does telling these narratives in this way, as opposed to reading about deportation solely in the media, add to our understanding of the individual lived experiences of deportation?

There’s a lot of talk about ‘giving voice’ in social research, which sounds (and is) pretty icky. But when taken literally, voice as in the sound of someone’s voice, I think it can be really powerful, especially with deportation stories. Hearing the voices, the accents, of the people in my book makes my argument for me; the title ‘Deporting Black Britons’ suddenly makes sense when Chris or Kemoy speak in their London accent on a microphone. There’s also the sonic register of the voice, the way people speak, pause, laugh, sigh, speed up, backtrack, that all gets flattened out of the interview transcript, and I think the Deportation Discs puts some of that back in.

Then, of course, there’s the music. I love Desert Island Discs on Radio 4, at least as a format. I think segments of life story interviews interspersed, or interrupted, by their accompanying soundtrack is a wonderful way of telling and sharing. Doing this with deported people was really powerful, and the music choices were ones you rarely here on the BBC. I found that deported people were also especially likely to think about a soundtrack to their lives in a really intelligent and considered way. I think people who have been incarcerated and then deported spend a lot of time reflecting on different moments in their lives, how it could have been different, where the turning points were, and how they came to where they are. It makes for a powerful conversation.

What are you currently working on?

A few bits. I am one of eight authors on a collectively written book Empire’s Endgame: Racism and the British State, which is out in February 2021 with Pluto Press. It’s not an edited collection where we each write chapters, but a full book written by all of us, which was a fun process! I’m also working on a co-authored book with Gracie Mae Bradley on border abolition, which will be out later in 2021. Then I would like to take a rest from writing projects for a while!

I’m starting at UCL in January, as a lecturer in the new Sarah Parker Remond Centre for the Study of Racism and Racialisation. The centre is headed up by Paul Gilroy and along with him and my new colleague, Paige Patchin, we’ll be developing an MA programme in Race, Ethnicity and Postcolonial Studies. So that’s really exciting. The centre has a particular interest in research on data, climate and health, so I’m sure these core areas will shape my future research on issues surrounding ‘race’ and racism.

What is the most important advice you could give to young scholars?

Research things you care about. The feelings of self-doubt and the constant reminder that you haven’t read enough don’t go away, and all of it is only made manageable by studying things that matter, with others, and learning from unexpected sources. Find comrades and contemporaries to talk and think with, and don’t over rely on PhD supervisors. The university can be a refuge, but it’s also a pretty messed up place, where student debt makes salaries and from which most people are excluded. Radical and interesting ideas happen elsewhere too, so don’t get too comfy, and plan for the revolution :).