Popular Culture, Geopolitics and Identity

Jason Dittmer and Daniel Bos

Rowman & Littlefield, Second Edition, 2019

It is one thing to hold that popular culture writes the global space but another to demonstrate the various ways by which this happens. Doing so in a manner that brings out the complex of social theory, history, definitive concepts and practices underpinning each of the ways by which popular culture unfolds must be the element of mystique compelling constant reference to the second edition of Popular Culture, Geopolitics and Identity. It makes the book byJason Dittmer and Daniel Bos of the University College London and Oxford University, respectively a compelling reference on discourse productivity.

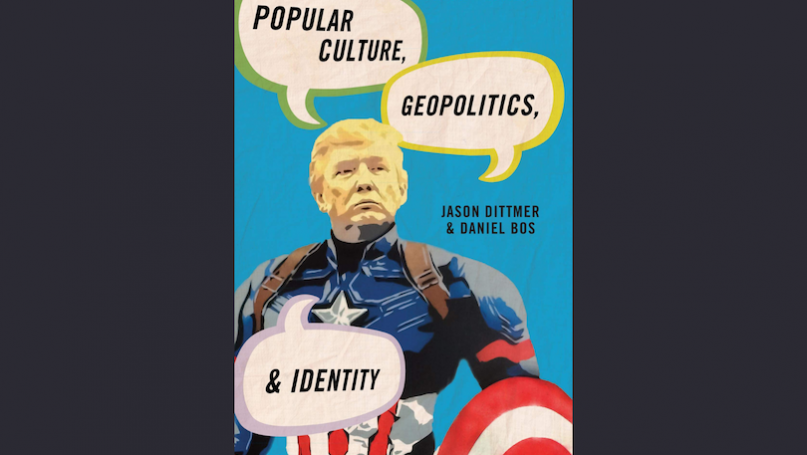

The second edition is a highly improved version of the first in, among others, the picture of Donald Trump on the cover and the representational message in that vis-a-vis the study of popular culture; the innovation of concept boxes for a more precise sense of slippery concepts throughout the book and, above all, the whole new chapter on methodology. That is, methodology on researching popular geopolitics but also as a response to the crisis of philosophy of science in social research. In all, each of the nine chapters of the 2019 publication arguably leaves the reader with something to think further about in relation to how linguistic activities generated on platforms of popular culture enact the spatial reality invoked in phrases, cliches, metaphors, narratives, images, sound bites and concepts.

On the whole, this book leaves the reader with a heightened awareness of why otherwise very ordinary cultural cum entertainment productions such as TV soap operas, comic books, newspaper articles, films, literary texts, narratives, musical numbers or internet content could be linked with the struggle for power in global politics. The book explains how this happens through the frames of intelligibility about one place, culture, or nation that cultural productions circulated on platforms of popular culture embody and are culturally ‘read’ by their audiences as to be implicated in constituting geopolitical identity. What this means is that binaries of friendly/hostile, hot/cold, civilized/barbaric, rational/irrational, peaceful/violent and many others applied to this or that nation, culture, people or place on platforms of popular culture have constitutive force.

Exemplifying Popular Culture in Action

The reader encounters intriguing examples of the force of action popular culture can unleash in world politics through such frames of intelligibility embedded in cultural productions. Of note here is the 2014 hacking of Sony’s systems in relation to the film The Interview, allegedly carried out by the North Korean leadership uncomfortable with the storyline of the North Korean leader being assassinated by his potential interviewees acting out a CIA brief. It provides a very good example of how a typical popular culture product could provoke a high-stakes geopolitical tussle, involving Hollywood actors, organisers and financers of the international film festival, American movie connoisseurs threatened by North Korea, the CIA and the American State. Another example would be the significance the North African/migrant identity of 17 out of 23 players making up the 2018 French men’s football World Cup team came to acquire. Or, how there could be a place today known to everyone as the Middle East, suggesting East of a centre which was the British Empire of yore.

The way each chapter flows into the next in this book makes it difficult to talk about it in terms of sections or parts but it still makes sense to compartmentalize the first three chapters into a segment; chapters Four to Eight into another while Chapter Nine stands alone. The first three chapters constitute an excursion into the subject matter of Geopolitics as an academic realm; the tension within it which gave rise to the critical challenge to Classical Geopolitics; the birth of Popular Geopolitics as a niche and the theme of how Popular Geopolitics might be researched. These chapters would still fascinate even the not so academic minded reader when it comes to the challenge posed by the sub-discipline of Critical Geopolitics, which argues Geography is what we make of the earth and not what the earth makes of (world) politics as is upheld in Classical Geopolitics. Chapter Two explains the emergence of Popular Geopolitics within Critical Geopolitics as basically the study of the constitutive force of representations or discourses in relation to global power politics.

Each of chapters Four to Eight takes a particular concept or practice by which popular culture performs geography and geopolitical identity. Chapter Four is certain to be devoured with unparalled attention, irrespective of national, cultural, ideological or gender identity of the reader. The chapter tells the story of how the British used popular culture, particularly literature, film and cartoons to get on with Empire in spite of the Enlightenment principles of rule of law and equality of all which Empire contradicted. It is there in the contrast between the opulence of Empire, symbolised by Mansfield Park in Jane Austen’s novel by that name and its spatial Other, with the life of the character Fanny, for example, illustrating the contrast. The silence on sugar production in the Caribbean as the material source of the prosperity in the estate shows literature functioning to script the world in line with the logic of Empire. In other words, imperialism and neo-colonialism became real through a strategy of ‘keeping the subordinate subordinate and the inferior inferior’ as articulated in Edward Said’s Culture and Imperialism, (p.95). So also is the case of James Bond which illustrates Britain’s deployment of film as an instrument of identity constructivism, with Bond enacting the stature of the guarantor of Western Civilisation even in the aftermath of decolonization. Interesting here is the point about ‘silence’ or non-representation as a form of (mis)representation, exemplified by Africa basically missing from Bond’s itinerary.

Most readers would equally find Chapter Five interesting, depicting how Captain America, the superhero in that comic series, enacted the United States in accordance with her self-image as an innocent nation that is always threatened by an evil other/outsider and how she always prevails. But the point of the superhero in Captain America is how national histories have much less to do with what actually happened in history but much more with the representation of what might have happened. In all cases, what might have happened is not rationality or facts all the way down but about how myths and morals are plotted into a narrative and circulated on purpose.

Popular Culture Beyond the Representational

The tempo changes in chapters six to eight as the book turns to materialist geopolitics. Each of the three chapters show a different non-representational process, beginning with the “affective logic of mediated spaces”, (p.123). Chapter Six uses military-themed video games to demonstrate how this vastly popular platform immerses the player in militarism or the beatification of state violence as not only pleasurable but also an entertaining consumption. The resulting militainment – the merger of military technology with entertainment – has the prospect of making the average player an instinctive promoter of three ideologies. The book lists these as the notion of ‘clean war’ and, by implication, the insensitivity to costs of war that comes along; techno fetishism or the celebration of military weapons without a care for victims and, lastly, the culture of unquestioned support for ‘our troops’ on the ground of the national idea or patriotism. Although, military-themed video games are rarely produced by the military itself, they are not without the military messaging that makes them serve as a conveyor belt of the militaristic orientation of the Military-industrial complex, now reworked into the Military-Industrial-Media-Entertainment Complex.

In Chapter Seven, the same theme is further explored under the idea of assemblage or thinking beyond the consumer of popular culture texts to the orientations or moods, narratives, rituals and practices brought into consumption, which warrants the associated concept of performative consumption (p.146). This claim is illuminated by how the audience decodes a particular heritage site – the Australian War Museum. A different realm in materialist geopolitics unfolds in Chapter Eight. At stake here is the way communication technologies – the telegraph, telephones, radio, television and the internet – have occasioned the reality of “distanced witnessing” and with it, the possibility of the individual being in several places at the same time, affecting and being affected by others on Facebook, Twitter, Skype, amongst others. “Distanced witnessing” transforms to the idea of the “networked self” – the individual as an assemblage resulting from the “intensification of social relations that comes with social media” (p.167) and the spatial implications of that due to the great distances involved. Geopolitically, the way the ‘networked self’ tends to give an online character to the concept of the public sphere attracts attention here. Other than the debate over control of algorithms by digital monopolies, the big question here is what governments do with their own algorithms which, unlike those of social media giants, are out of public oversight. Under the concept of digital diplomacy, this book uses the much talked about Russian intervention in the 2016 US Presidential Election to illuminate this.

Deflecting Criticism, Recalling Controversy

The book’s illumination of the institutional, agency and practices by which non-representational processes work frees it from the criticism that representation alone is not enough in accounting for geopolitical outcomes. Representation must be theorised along with the complex of structures, institutions and practices that account for performativity. However, as much as the three chapters on non-representational theory respond to that criticism, they equally remind readers of the contention articulated in particular by Charlotte Epstein of the University of Sydney. She argues that discourse or ‘the power of words in International Relations’ had not been exhausted before what she observes to be “a huge nostalgia for the concrete and the tangible” that led to the embrace of non-representational theories in the humanities. The clincher from Epstein is how the switch reckoned little with the history of social thought where discourse and practice or the ideational and the material have actually been indistinguishable except in what she would pass as the wrong headed materialist critique of Hegel. In other words, the three chapters collectively raise the question of the extent to which critics of a Chinese Wall between representational and non-representational practices have a point in the study of Critical/Popular Geopolitics.

A similar question of a general nature in the discipline rather than a deformity internal to the book is the question whether it is possible to talk of a defining character of popular culture. On the one hand is the revolutionary or emancipatory potential inherent in the capacity of some popular culture texts to subvert hegemonic scripts. This point has been well made in the book and elsewhere, particularly by Luke and O’Tuathail as well as Lene Hansen. But, on the other hand, this tends to be contradicted by the chauvinism or conservatism of most self-representation of geopolitical actors. How far then can we talk of popular culture in emancipatory terms, especially in cases of unequal power relations, given the shifting nature of power based on hegemony?

Notwithstanding these sorts of questions, it is almost certain that this book will appeal to a much broader audience than the advanced undergraduates and fresh graduate students that the authors specify as the target audience. Editors, journalists involved in reporting distant lands, publicists of military campaigns, diplomats, think tankers, intelligence operatives and field officers of INGOs are bound to find it fascinating. This is more so on account of the simplicity of the language and the completeness of the engagement with how popular culture constructs the global space for popular geopolitics to emerge as such a fascinating meeting point of knowledge. This should no longer be surprising. For, if war itself, as Sam Keen argues in his Faces of the Enemy: Reflections of the Hostile Imagination, is preceded by the practice of inventing the enemy and thinking him, her or them to death before inventing the weapons that will crush such enemies to death eventually as Yugoslavia or Rwanda shows, then popular geopolitics must be the master subject. This is in the light of the scale of constructedness in world politics.

Popular Geopolitics has witnessed a wave of publications in recent years. Among these are Popular Culture and World Politics: Theories, Methods and Pedagogies; Understanding Popular Culture and World Politics in the Digital Age; Popular Geopolitics and Nation Branding in the Post-Soviet Realm; Geographies, Gender and Geopolitics of James Bond;Popular Geopolitics: Plotting an Evolving Interdiscipline. Popular Culture, Geopolitics and Identity certainly serves as both a ‘foundational’ text in itself as well as a powerful addition to these publications which have, individually and collectively, contributed to accomplishing Robert Saunders’ idea of the movement of popular geopolitics from the margins to the centre in International Studies/Political Geography scholarship. It is hoped that, in the event of a third edition or by way of a sequel, the authors would give attention to their inability to have advanced the cause of geographical inclusivity higher by drawing on wider spaces of popular culture beyond the US and the UK. While noting the fear of the authors regarding the accuracy of the book if they drew on cultural spaces outside of their specialist radius, it is doubtful that can overwrite the case for inclusivity here.