Zhejiang province is situated south of Shanghai and is considered to be one of China’s richest provinces. It also holds one of China’s largest concentrations of Christians and while they have been living in the area for many decades, recently they have come under increasing political pressure. In 2014 alone thirty churches were demolished, 422 crosses were removed, over 300 people were taken into police custody, 150 people were physically harmed by the authorities and over 70 Chinese Christians were prosecuted, among them church leaders and prominent members of the local clergy (Rotenberg, 2018). These numbers are exemplary for the intensification of religious repression in China in recent years. Since Xi Jinping has taken power, state control over religious rights and liberties has expanded relative to the eras of Hu Jintao and Jiang Zemin before him. However, the tightening of political control over religious groups as well as individual believers should be considered in a broader sense than simply the restriction of civil liberties.

Since Xi has taken over the reigns in late 2012 he has set out to accelerate a foundational change in the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and Chinese society regarding the legitimacy and power position of the party by embedding an alternate master narrative. Exercising political control over religion is one of the avenues by which he seeks to achieve this end. Since the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, the CCP has derived its legitimacy to rule form the communist ideology on which both the party and the state are grounded. Yet, after the 1978 reforms, China has increasingly embraced market led capitalist principles, eroding its claim to legitimacy based on the communist ideology (Jinghan, 2014).

To reinforce the CCP ́s claim to power, Xi and his administration have adopted the concept of the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation as a leading principle. While this is by no means a new narrative, the degree to which it is employed by the Xi administration is. It shows the value attributed to the concept as a new guiding principle for the Party and therefore the state. Xi’s institutionalization of the concept of rejuvenation of the Chinese nation is simultaneously grounded in, and constitutive of, increasing nationalist sentiments in the Chinese society and the socio-political discourse (Zheng, 2013). In this essay, the consequences of Xi’s reliance on these nationalist sentiments will be assessed as it relates to religion in China. To reinforce national unity and Chinese feelings of collectivity, the administration is actively securitizing religion. It seeks to establish a narrative in which religion is presented as an existential threat to the fabric of China’s national identity by means of a set calculated rhetorical acts conducted in the socio-political sector (Rotenberg, 2018; Vermander, 2018; Wai-Yip, 2019).

To understand the efforts made by the administration, the first two sections of the essay will provide a brief analysis on the CCP legitimacy crisis and the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation sketching the broader political reality facing China in which the policies towards religions should be understood. Subsequently the main section on the securitization of religion will follow. This analysis consists of three parts, first of which is a historic overview of the position of religion in the PRC. What follows is an assessment of Copenhagen School Securitization Theory which provides a theoretical framework through which to understand the relation between politicization and securitization. Lastly, the sinicization of religion will be assessed through the Copenhagen School framework which indicates current policy goes beyond mere politicization and in fact constitutes securitization of religion.

The CCP’s Legitimacy Crisis

Since the 1978 reforms it has often been debated that China and the CCP would be at risk of, or engaged in, a legitimacy crisis (Zhong, 1996; Holbig and Gilley, 2010; Chu, 2013; Xiang, 2020). The notion of a legitimacy crisis stems from the fact that since the establishment of the PRC in 1949, the CCP has ruled China based on a communist and later a Maoist ideology. These ideological underpinnings formed a clear structure legitimizing the one-party rule of the CCP (Robinson, 1988; Lary, 2008; Jinghan, 2014). However, the 1978 reforms meant a gradual adoption of market-led capitalist principles in nigh to all sectors of the Chinese economy. This enabled the economy to produce unprecedented economic growth numbers, lifting hundreds of millions of people out of poverty and turning China from a developing country into the second largest economy in the world (Ma, 1999; World Bank, 2019). However, it has also made it increasingly difficult to square CCP one-party rule based on Maoist ideology.

The developments mentioned above have led some to argue that the CCP’s legitimacy to rule is eroding and that popular support for the party is dwindling. It can be argued that there are roughly three schools of thought to be recognized in this debate representing distinct arguments related to CCP legitimacy (Yun-Han, 2013). Many western political commentators argue that the regime actually operates with a severe deficiency of political legitimacy causing the seemingly stable one-party state system to be very fragile. Over the course of the 2000s, many academics advocating this particular view called attention to the surge of so-called ́mass incidents ́ throughout the decade, the ever-growing costs of security expenses for both military and police activity and the strong responses from the government concerning the Color revolutions and the Arab Spring (Chen, 2010). These observations would suggest that the CCP does in fact not hold such a tight grip on political power in China. Thus, engaging in political reform is inevitable. A prominent proponent of this view is David Shambaugh, he argues that the ever-increasing repression of the regime is a sign of its weakness and is indicative for the “cracks in the regimes social control” (Shambaugh, 2015). The only reason for the current persistence of the regime would be the continuous, albeit stagnating, economic growth masking the legitimacy deficiency sufficiently for the CCP to remain in power.

Contrary to this view two other schools can be distinguished. Firstly, the institutionalist perception of government legitimacy postulates that the regime harnesses its legitimacy from the degree to which it has institutionalized its customs and structure on the political society. The institutionalist school recognizes the importance of socio-economic performance of the policies implemented by the regime and nationalist sentiments in the Chinese society. However, it argues these are in fact resulting from the institutionalization of the party. Additionally, the Party’s ability to constantly adapt to changing domestic, international and technological environments provides it with the capabilities to actually guide public demands and use them in an effort to foster national unity and sympathy for the Party (Yun-Han, 2013; Zhu, 2018) Lastly, there is a more fundamental critique on the concept of legitimacy itself which would be derived from western ideas based on the work of Max Weber and David Beetham. This school of Culturalism, led by figures such as Yangqi Tong and Daniel Bell, argues that the legitimacy of the regime does not stem from economic performance or political embeddedness but from historically defined roots of state-society relations. This is a much more moralistic approach towards legitimacy based in Chinese ancient culture, relying heavily on Confucian principles such as benevolence and care (Yangqi, 2011; Yun-Han, 2013; Bell, 2015).

The Party’s legitimacy to rule, which remained seemingly undisputed in the Mao era, is now something that is being questioned. While the reformist view certainly has its merits with its emphasis on the importance of economic growth and the regimes conservatism vis-à-vis foreign popular movements, it seems hard to uphold the argument that market-led capitalism is ultimately irreconcilable with authoritarian governance due to the ongoing economic growth of the Chinese economy and the relative stability of the regime over the past four decades, especially under Xi Jinping (Bell, 2015). Similarly, Culturalism rightfully points out the western centrism of the concept of legitimacy and importance of the distinct cultural tradition of China. It is absolutely essential to take into account the long tradition of Chinese political and societal thought when engaging in analysis of any political event in China, but it seems unlikely that in the rapidly modernized Chinese society historically ingrained patterns can be sufficient to constitute the bases for CCP’s political legitimacy. The institutionalists are right that the degree to which the Party and its governance structure are embedded in the political as well as social sphere are a key component for continuous legitimacy claim of the CCP. Howbeit, this provides a rigid structure needing ideational input which the institutionalist approach seems to neglect.

One of the reasons why Maoism provided a sound foundation for CCP rule was the fact that it not only provided a clear organizational foundation for society but also united the nation behind an ideological banner. The institutionalist approach provides a similar organizational rigidity but lacks the ideological component previously provided by Maoism. Looking at contemporary CCP policy, nationalism seems to be acting as the present-day equivalent to Maoism in that it provides the ideational input for the organizational system outlined by the institutionalists. Hence, the emphasis placed on nationalism by the Xi administration through its actions as well as its rhetoric does not merely represent a shift in policy. Rather, it should be considered a more foundational shift in the manner in which the party seeks to legitimate its rule.

The Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation

The gradual shift from a Maoist based foundation of legitimacy to a nationalist based foundation is largely brought about by means of a rhetorical process. The great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation is the concept central to this effort. While the term has been used previously, the Xi administration has made it a cornerstone of its policies and has presented it as a pivotal concept in the development of the country.

The great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation is a concept that has been employed by different Chinese leaders over the last century. Starting with Sun Yat-sen and Jiang Jieshi in the 1910s and 1920s up to the administrations of Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao in the 1990s and the 2000s, all have drawn on the concept of the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation, albeit all framing it somewhat differently (Zheng, 2013). While different leaders deployed distinct rhetorical methods to exploit the concept of rejuvenation, the general premise has remained broadly the same. It relies on the “humiliation narrative” and the need for China to reclaim its rightful place as a powerful nation on the global stage. This was allegedly taken from the Chinese people by foreign intruders, starting in the mid-19th century, ushering in the century of humiliation which saw China’s power diminish and allowed other countries to exploit the Chinese nation and its people. Subsequently, the narrative postulates that the great humiliation can only be remedied by rejuvenating the Chinese nation. In practice, this means that those calling for rejuvenation appeal to the national identity of the Chinese people to unite behind the leadership and reclaim the power that was taken away from them and their country. William Callahan and Peter Gries both argue that the century of humiliation has been the master narrative in modern Chinese history and that Chinese nationalism can only be understood by taking this as the point of departure (Callahan, 2004; Gries, 2004).

When in 1949 the party state was established, the CCP proclaimed the century of humiliation to be over. With Mao as the paramount leader, the PRC set out to restore its former glory. However, this was not done by calling on the humiliation narrative. It took until 1989 before the concept reappeared in the Chinese political discourse. Prior to 1989, communism and advancing the revolution had formed the master narrative of the CCP. Yet, after Mao’s death the Maoist ideology that had guided the party, and by extension the country, proofed increasingly unable to act as an ideological bedrock. Subsequently, this resulted in the ‘Three Belief Crisis’, a crisis of faith in socialism, a crisis of belief in Marxism and a crisis of trust in the CCP, meaning the party needed to find a new way to unite the nation behind the CCP (Chen, 1995). Over the decades that followed, Jiang and Hu identified nationalism as an appropriate vehicle to do just that and sought to thoroughly embed a nationalistic master narrative derived from the humiliation narrative through political theories, such as Jiang’s Three Represents and Hu’s Harmonious Society. These efforts can be observed by assessing rhetorical acts such as their respective speeches to the National Congress over the years (Jiang, 1991; Jiang, 1996; Jiang 2002; Hu, 2007).

When Xi Jinping took office in 2012, he not only underscored the emphasis on the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation, he doubled down and set out to formulate his own approach towards socio-economic development; the Chinese Dream, which is largely based on the concept of rejuvenation. Xi’s Chinese Dream builds on the work of Jiang and Hu and the unifying nationalist sentiments that had been fostered by their attempts to embed the new master narrative. Yet, the Chinese Dream does rely on a different approach to progress compared to earlier policy or development theories based on rejuvenation. Where earlier approaches stressed the humiliation and suffering of the Chinese nation as essential elements, the Chinese Dream reasons from a point of strength and has a much more explicit focus on obtaining prosperity and advancements on its own merits. This more positive, self-confident interpretation of the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation is heavily reliant on identification with the national identity associated with the concept. Hence, the Xi administration is dependent on nationalist sentiments which it thus seeks to promote (Edney, 2015; Wang, 2017; Bhattacharya, 2019). This reliance on national unity based on nationalism can also be associated with China’s increasingly assertive stance on foreign policy under Xi Jinping and has also caused its domestic policy to exhibit traits fostering these sentiments. Examples of such domestic policies can be found in education as well as in the handling of religion within China.

Securitization of Religion

A History of China’s Religion Policy

Religion in the PRC has had a rocky history ever since 1949. It has always been a contested topic for both the country and the party. The party ideology is based on Marxism, and Marx viewed religion as being a product of society and argued its eventual abolition was essential to achieve revolution and foundational societal change (Dillon, 2001; Lü & Gong, 2014). Considering this, the CCP has always advocated to be an atheist party. When the party state was founded it also adopted a policy of state atheism. However, the emergence of an atheist state did not automatically cause religious persecution. Until the start of the Cultural Revolution religious freedom was guaranteed in the constitution and believers were able to practice their faith in relative freedom (Constitution PRC, 1954: Dillon, 2001). However, when the Cultural Revolution started all forms of religious expression were prohibited and both traditionally Chinese- and non-Chinese religions were severely suppressed resulting in the closure and destruction of places of worship and prosecution of practitioners of any faith. Much of the infrastructure and organizational capabilities of religious groups were demolished over the course of the Cultural Revolution but after the death of Mao and the arrest of the Gang of Four in 1976 the tide began to change. Under its new leadership China was being reformed. While the economic reforms of 1978 have since become infamous, the economy was not the only sector experiencing significant changes. The 1978 constitution once again guaranteed the freedom of religion and this position was enforced by the issue of Document 19 in 1982 which officially recognized the party’s break from the repudiation of religion over the course of the Cultural Revolution. Document 19 also formalized the official recognition of Buddhism, Daoism, Islam, Protestantism and Catholicism by the state setting up five associated state organs tasked with regulating these five religions in China. (Constitution PRC, 1978; CCCCP, 1982; Laliberté 2015).

As a result of these measures, China has experienced a revival of both Chinese and non-Chinese religions since 1978. While the CCP has continued its policy of party atheism and the PRC therefore officially remains an atheist state, individuals were given the opportunity to practice their faith in relative freedom. The CCP’s leadership allowed religious groups to flourish since it accepted their ability to provide psychological and social support to the masses in a time where the state was rolling back involvement in people’s daily affairs (Goosart & Palmer, 2011). Hence, the state allowed religious freedom within a carefully designed framework. The framework set up by the CCP consists of three different institutional structures; the United Front Work Department of the CCP Central Committee, The State Administration for Religious Affairs (SARA), and the patriotic associations of the five state religions, who operate at every organizational level of the party state. Through these organizations, the CCP is able to monitor religious practices in the country. While this was initially designed as a pre-emptive measure over the course of the 1990s, it has gradually developed into an oppressive apparatus (Kuei-min, 2018). In response to the 1989 turmoil and a gradually changing perception of the political legitimacy of the CCP, the attitude vis-à-vis religion changed. Document 6 issued by Jiang Zemin in 1991 restricted many of the religious freedoms established by Document 19 nine years earlier and tightened political control over religious groups. In the following two decades state control over religion rose. The 1994 ‘Regulations on the Administration of Religious Venues’ issued by Jiang, and the 2005 ‘Regulation on Religious Affairs’ issued by Hu, have both limited the freedom of existing religious groups and obstructed the establishment of new religious organizations (Kuei-min, 2018).

While it becomes clear from this brief analysis that religion has always been a contentious and politicized topic in China under the Xi administration, religion has moved beyond simple politicization towards active securitization. Since 1989, religion has been regarded as a force that could potentially cause social unrest and was therefore increasingly politicized and put under active rather than passive state control. However, since Xi Jinping has taken office, the governments approach towards religion has shifted away from mere politicization. It has been identified by the Xi administration as a means to help attain the Chinese Dream. As set out above, the Chinese Dream is based on the concept of the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation and therefore relies on nationalism. Hence, where previous administrations limited religious freedom for reasons concerning social and political stability, the Xi administration has set out to construct a narrative in which certain religions and religious movements of a non-Chinese origin are not perceived as potential sources of instability in the socio-political realm, but rather, as existential threats to the Chinese Dream and therefore the prosperity and development of the Chinese nation. At the same time this move is balanced by a renewed interest in religions and religious movements considered to be traditionally Chinese for their supposed contributions to the rejuvenation of China (Xi, 2014a). This can be considered an indicator of an attempt to more fundamentally entangle the political as well as the public perceptions of religion with the nationalist sentiments which shows the administration has gone beyond politicization and is actively securitizing religion in China.

Securitization

Defining security or securitization is no simple matter. Amid the Cold War, security concerns were largely defined along a narrow line, solely encompassing military, and more specifically, nuclear dimensions. Traditionalists such as Colin Gray argue that security does not necessarily need to be state centric but that a defining characteristic of a security issue is that it always needs to concern a military dimension (Walt, 1991; Gray, 1994; Buzan and Hansen, 2009). However, at the end of the Cold War, an increasing number of academics started to argue for a wider interpretation of what could potentially entail a security concern. Arguably, the most elaborate framework theorizing a new approach towards security analysis was provided by Buzan, Waever and de Wilde constituting the foundation of the Copenhagen School of Security Studies. The Copenhagen School argues for a wide interpretation of security with a specific focus on non-military security threats. In their 1997 book, they define security as those issues that can be distinguished from the normal routine of the political process due to the fact that they supposedly form an existential threat to a particular referent object according to the securitizing actor. This threat would in turn allow the latter to go beyond the bounds of mere politicization and expand its abilities to act by extraordinary means to contain the threat. They determine five sectors, the military, the environmental, the economic, the societal, and the political sector, in which distinct forms of interaction among multi-level actors can be identified.

Depending on the respective sector, different organizing concepts are singled out constituting the core of the sectoral interest. Additionally, the school questions the desirability of security. Alternatively, they claim desecuritization should be pursued rather than security itself. Security is argued to be the extreme extent of politicization and therefore indicates the inability to deal with a certain issue by ordinary means. Yet, this in and of itself can be the objective of a securitizing actor creating a wider range of options for the actor to address a certain issue. Hence, a security issue does not exist on its own merits. It is the product of a rhetorical act, also known as a securitizing move, by a securitizing actor presenting a certain issue as an existential threat (Buzan, 1991; Buzan et al, 1997). The success of the securitizing move is dependent on the degree to which the respective audience accepts the threat thesis put forward by the securitizing actor.

Traditionalist, often associated with the neo-realist and liberalist traditions in international relations scholarship, have noted that the broadening of the concept of security reduces its practical applicability to such an extent that it, in the best of cases, produces an interesting observation with no practical value and, in the worst of cases, strips the field of security studies from all its analytical value (Deudney, 1990; McSweeney, 1996). Additionally, proponents of more critical international relations theories, such as Jef Huymans and Lene Hansen, have argued that despite the wider interpretation of what can potentially constitute a security issue, the Copenhagen School still operates within an inherently conservative framework (Huysmans, 1998; Hansen, 2000). That being said, while both positions provide valid critique on the framework, it is undeniable that the Copenhagen School’s interpretation of securitization at the very least provides a helpful instrument to more critically assess acts by power holding actors. Hence, regardless of the practicality of the findings or the critical nature of the framework it does provide a distinct analytical perspective through which government action can be understood. It is for this reason that the Copenhagen School’s interpretation of securitization provides a framework through which to aptly understand the changing religious environment in China.

Sinicization of Religion

The Copenhagen School securitization framework provides an unconventional scope by which to analyse religious policy in the Xi Jinping era. As mentioned earlier, religion in the PRC has always been subject of political influence. Religious groups have been subject of increasing interference by government actors since 1989 as the aforementioned policy schemes introduced by Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao can attest. This tightening of control has prolonged under Xi, be it under different circumstances. The Chinese Dream narrative propagated by Xi has had far reaching consequences for religious groups in China. Looking at the securitization framework, these can be classified within both the societal and political sector. The organizing principle central to the societal and political sectors are national identity and stability of the social order respectively. A securitizing actor needs to challenge these principles and position the supposed security issue as an existential threat to the latter. Since the 19th Congress of the Chinese Communist Party the regime has repeatedly called for sinicization of religion which seems to be in accordance with the pattern laid out in the Copenhagen School framework..

Sinicization of religion is a relatively new issue facing religious movements in China and is therefore a concept which remains relatively ambiguous. The term was coined by Chao Wang and Shining Gao in late 2012 as part of their religious ecology of China theory. This entails that, akin to a regular ecological system, states enjoy a certain religious equilibrium in which the different religious groups keep one another in check. Following from this, Wang and Gao argue that the growth of primarily Christianity upset the delicate religious ecology of China resulting in the erosion of Chinese cultural traditions. This could be resolved by what they call the sinicization of Christianity, which would entail the inclusion of traditional Chinese cultural traits in the Christian tradition. Simultaneously, the theory urges governmental actors to promote indigenous Chinese religions such as Daoism and Chinese Buddhism in an effort to protect the balance of the religious ecology of China (Wang & Gao, 2012). The notions articulated by Wang and Gao ventured beyond academia and were popularized among the Chinese political elite. Thus, in 2016 the concept of sinicizing religion was mentioned by Xi Jinping in a speech addressing the United Front Work Conference on Religious Work. In the speech, Xi argued that all parts of Chinese culture should “match the needs of China’s development and the great traditional culture and pro-actively fit into the Chinese characteristics of a socialist society” (Xi, 2016). Adding in his address to the 19th Party Congress that the state needs to “uphold the principle that religions in China must be Chinese in orientation and provide active guidance to religions so that they can adapt themselves to socialist society” (Xi, 2017). The regime defines sinicization as a nationalistic obligation for the authorities to protect the Chinese society from foreign influences and uphold Chinese cultural traditions.

Hence, the regime has taken the concept of sinicization of religion out of the academic sphere and translated it into a political reality in which it constitutes an instrument helping to achieve the Chinese Dream. Alternatively, according to Richard Madsen, the sinicization of religion should not be seen as a measure to protect or promote Chinese culture, but rather, as a new means to enforce religious oppression. He argues that it cannot be labelled the Chinese version of indigenization since it does not seek to promote genuine Chinese tradition. The aim of institutionalized sinicization of religion is to embed traditional and historical narratives approved by the party into the popular discourse, and in doing so achieve stability on its terms (Madsen, 2019).

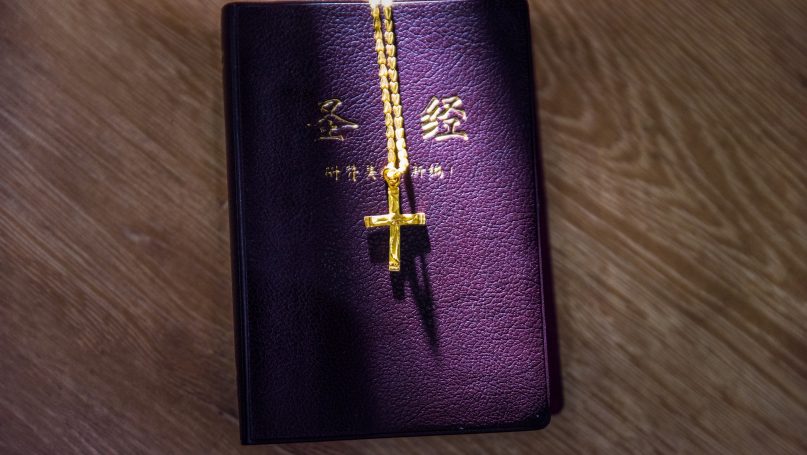

Since 2012, countless cases of ’sinicizing actions’ have been recorded supposedly in an effort to sinicize religion and protect Chinese culture. In the Christian community, this has led to the removal of crosses in and around churches, the forced closure of places of worship, bans on the sale of bibles that are not approved by the regime and incarceration of vocal clergy (Rotenberg, 2018). In the Muslim community, similar restrictions have been put in place. Most well-known are the so-called “re-education camps” in Xinjiang province. But besides mass incarceration, many public expressions of faith have been banned. As of 2017, measures illegalising long beards and veils have been in effect in Xinjiang and large parts of Ningxia, Shaanxi and Gansu provinces. Additionally, in the past decade there have been many instances of the destruction of domes and Arabic script from mosques and halal shops and restaurants on account of it promoting extremism. The two other officially recognized religions, Daoism and Chinese Buddhism, do not suffer such extreme conditions and actually receive limited governmental support since they are considered to be traditionally Chinese and therefore do not constitute an existential threat to national identity or social order. However, these movements too are expected to adhere to sinicization principles and are therefore expected to incorporate socialism with Chinese characteristics in their practices and change their behaviour accordingly. This indicates that the sinicization of religion pursued by the regime is the political interpretation of the original concept since the insistence on the incorporation of socialism with Chinese characteristics in traditional Chinese religions reveals the regimes political objectives veiled as an effort to protect Chinese culture.

The experiences of these officially recognized religions do seem to suggest that the argument put forward by Madsen, that sinicization constitutes a new era of repression, is valid. Yet, when we consider the Copenhagen School securitization theory it becomes apparent that not only the argument made by Madsen is in fact true, it goes far beyond simple political repression. Assessing statements made by Xi and other high-ranking government officials it becomes clear that they seek to position primarily non-traditional Chinese religious movements as destabilizing elements endangering the prosperity of the Chinese nation. Hence, they employ a securitizing move by means of speech acts in an effort to convince the audience, being the Chinese people, that religious movements are existential threats to the organizing concepts of the political- and societal sectors, these being the stability of the social order and national identity.

Starting with Xi’s 2016 speech to the United Front Work Conference, in which he politicized the religious ecology theory and set out his interpretation of sinicization of religion, the administration has engaged in countless speech acts enforcing the image of religion as an existential threat to stability and prosperity. On a 2016 conference on Religious Freedom in China, Xi stated that the Chinese nation should “resolutely guard against overseas infiltrations via religious means and prevent ideological infringement by extremists” enforcing the idea religious movements constitute foreign threats to Chinese unity (Wong, 2016). This idea was reiterated by Xu Xiaohong, head of the state-led Movement of Protestant Churches, stating that “Anti-China forces in the West are trying to continuously influence China’s social stability and even subvert our country’s political power through Christianity, and it is doomed to fail” adding that “only by continually drawing on the fine traditions of Chinese culture, can China’s Christianity be rooted in the fertile soil of Chinese culture and become a religion recognized by the Chinese themselves,”(Xu, 2019).

Additionally, there are multiple instances where the relation between terrorism and religious movements has been emphasized by Xi adding to the narrative of religions destabilizing effect on the Chinese society (Xi, 2014b; Xi, 2014c). The repression experienced by the different religious groups suggests that the securitizing move by the central government is being accepted by local governments resulting in localized crackdowns on religious freedom. Whether the general public is accepting the move as well is beyond the scope of this essay but the increasing nationalistic sentiments in the Chinese society at large is a telling sign. The Xi administration is engaging in the most restrictive religious policy since the Cultural Revolution and does this on nationalistic terms. Additionally, the Copenhagen framework shows that in the decades since the 1978 reform religion has always been under political control and religious freedom. Furthermore, it has never been absolute in the PRC, the Xi administration has extended this to unprecedented levels. Since 2012, the regime has actively pursued a strategy of securitization of religion over mere politicization and in doing so justifying its use of extraordinary means to protect the national identity and the stability of the social order form the supposed existential threat religion poses to the latter.

Conclusion

As this essay has shown, religion in China is a difficult matter. While the first decade of the post-Mao era saw a religious revival, since 1989, political control and repression have been rising. Yet, the actions undertaken by the Xi administration go beyond the tradition of mere political repression of religious expression. Under Xi Jinping, the regime has purposefully sought to securitize religion. By deploying the Copenhagen School securitization framework, it becomes apparent that the administration attempts to present non-Chinese religions as existential threats to national unity and social order. Presenting these religions as such legitimizes the regimes use of extraordinary measure to address them, and, in doing so, supposedly protect unity and order.

The narrative employed by the government to this end is grounded in nationalistic sentiments for the securitization of religion is not an end in its own right. It should be considered as a small part of the much larger effort of the Xi administration to redefine the master narrative on which the CCP’s rule is founded. Since the 1989 ‘Three Beliefs Crisis’, consecutive Chinese governments under Jiang Zemin, Hu Jintao and now Xi Jinping have increasingly relied on nationalist sentiments to legitimize one-party rule. The Chinese Dream, as further articulated by Xi is supposed to embed the new nationalistic master narrative for CCP legitimacy indefinitely. Thus, controlling religion is one part of this effort. Hence, the Xi administration is engaging in the securitization of religion since it contributes to the enforcement of a new master narrative on which the CCP can base its legitimacy.

References

Bell, Daniel. (2015). The China Model: Political Meritocracy and the Limits of Democracy. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Bhattacharya, Abanti. (2019). Chinese Nationalism Under Xi Jinping Revisited. India Quarterly. 75(2). 245-252.

Buzan, Barry. (1991). People, States and Fear: An Agenda for International Security Studies in the Post Cold War Era. Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publisher, Inc.

Buzan, Barry and Lene Hansen. (2009). The Evolution of International Security Studies. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Buzan, Barry, Ole Waever and Jaap de Wilde. (1997). Security: A New Framework for Analysis. Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publisher, Inc.

Callahan, William. (2004). National Insecurities: Humiliation, Salvation, and Chinese Nationalism. Alternatives. 29. 199-218.

Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCCP). (1982). Document 19. Chinese Communist Party.

Chen, Jie. (1995). The Impact of Reform on the Party and Ideology in China. Journal of Contemporary China. 4(9). 22-34.

Chen, Titus C.. (2010). China’s Reaction to the Color Revolutions: Adaptive Authoritarianism in Full Swing. Asian Perspective. 34(2). 5-51.

Chu, Yun-han. (2013). Sources of Regime Legitimacy and the Debate over the Chinese Model. China Review. 13(1). 1-42.

Constitution of the People’s Republic of China. (1954). Chapter II. Article 36.

Constitution of the People’s Republic of China,. (1978) Chapter III. Article 45.

Deudney, Daniel. (1990). The Case Against Linking Environmental Degradation and National Security. Millenium: Journal of International Studies. 19(3). 461-476.

Dillon, Michael. (2001). Religious Minorities and China. London, United Kingdom: Minority Rights Group International.

Edney, Kingsley. (2015). Building National Cohesion and Domestic Legitimacy: A Regime Security Approach to Soft Power. Politics. 35(3-4). 259-72.

Gray, Colin S.. (1994). Villains, Victims and Sheriffs: Strategic Studies and Security for an Inter-War Period. Hull, United Kingdom: University of Hull Press.

Gries, Peter Hays. (2004). China’s New Nationalism: Pride, Politics, and Diplomacy. Berkeley, California: University of California Press.

Goossaert, Vincent and David A. Palmer. The Religious Question in Modern China. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press.

Hansen, Lene. (2000). The Little Mermaid’s Silent Security Dilemma and the Absence of Gender in the Copenhagen School. Millenium: Journal of International Studies. 29(2). 285-306.

Holbig, Heike and Bruce Gilley. (2010). Reclaiming Legitimacy in China. Politics and Policy. 38(3). 395-422.

Hu Jintao. (2007, October 24). Report at the 17th CCP National Congress. Presented at the 17th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, Beijing.

Huysmans, Jef. (1998). Revisiting Copenhagen: On the Creative Development of a Security Studies Agenda in Europe. European Journal of International Relations. 4(4). 479-505.

Jiang Zemin. (1991, July 1). Speech at the Meeting Celebrating the 80th Anniversary of the Founding of the Communist Party of China. Presented at the Meeting Celebrating the 80th Anniversary of the Founding of the Communist Party of China, Beijing.

Jiang Zemin. (1996, October 10). Speech at the 6th Plenary Session of the 14th CCP National Congress. Presented at the 14th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, Beijing.

Jiang Zemin. (2002, November 14). Report at the 16th CCP National Congress. Presented at the 16th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, Beijing.

Jinhang Zeng. (2014). The Debate on Regime Legitimacy in China: Bridging the Wide Gulf between Western and Chinese Scholarship. Journal of Contemporary China. 23(88). 612-635.

Jun Ma. (1999). The Chinese Economy in the 1990s. New York, New York: MacMillan Publishers.

Kuei-min Chang. (2018). New Wine in Old Bottles: Sinicisation and State Regulation of Religion in China. China Perspective. 16(1-2). 37-44.

Laliberté, André. (2015). The Politicization of Religion by the CCP: A Selective Retrieval. Études Asiatiques. 69(1). 185-211.

Lary, Diana. (2008). The Uses of the Past: History and Legitimacy. In André Laliberté and Marc Lanteigne (eds.), The Chinese Party-State in the 21st Century: Adaptation and the Reinvention of Legitimacy. (pp. 130-145). New York, New York: Routledge.

Lü Daji and Gong Xue Zheng. (2014). Marxism and Religion. Leiden, The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV.

Madsen, Richard. (2019). The Sinicization of Religion under Xi Jinping. China Leadership Monitor. 61(3). 12-22. Retrieved from URL: https://www.prcleader.org/sinicization-of-chinese-religions.

McSweeney, Bill. (1996). Identity and Security: Buzan and the Copenhagen School. Review of International Studies. 22(1). 81-93.

Robinson, Jean. (1988). Mao after Death: Charisma and Political Legitimacy. Asian Survey. 28(3). 353-368.

Rotenberg, Eloise. (2018). Xi Jinping ́s Sinocentrism and its impact on Religion: Modern Chinese Christianity Under Attack. New York University Journal of International Law and Politics. 50(3). 1057-1092.

Shambaugh, David. (2015, March 6). The Coming Chinese Crackup. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from URL: https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-coming-chinese-crack-up-1425659198.

Vermander, Benoît. (2019). Sinicizing Religions, Sinicizing Religious Studies. Religions. 10(2). 137-160.

Wai-Yip Ho. (2019). From Neglected Problem to Flourishing Field: Recent Developments of Research on Muslims and Islam in China. In André Laliberté and Stefania Travagnin (eds.), Concepts and Methods for the Study of Chinese Religions Volume I: State of the Field and Disciplinary Approaches (pp. 93-114). Boston, Massachusetts: De Gruyter.

Walt, Stephen. (1991). The Renaissance of Security Studies. International Studies Quarterly. 35(1). 211-239.

Wang Chao and Shining Gao. (2012). A Review of Thoughts on the Models of Religious Regulation: Beginning with “religious cultural ecological equilibrium”. Studies in World Religions. 5(1). 173-178.

Wang, Jiayu. (2017). Representing Chinese Nationalism/Patriotism through President Xi Jinping’s ‘Chinese Dream’ Discourse. Journal of Language and Politics. 16(6). 830-848.

Wang, Zheng. (2014). The Chinese Dream: Concept and Context. Journal of Chinese Political Science. 19(1). 1-13.

Wong, Cal. (2016, May 31). Why China Fears Christianity. The Diplomat. Retrieved from URL: https://thediplomat.com/2016/05/why-china-fears-christianity/.

World Bank. (2019). GDP (current US$) – China, United States, European Union, Japan, Germany and India. Retrieved from URL: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=CN-US-EU-JP-DE-IN.

Xi Jinping. (2014a, March 27). Exchanges and Mutual Learning Make Civilizations Richer and More Colorful. Presented at the UNESCO Headquarters, Paris.

Xi Jinping. (2014b, April 25). Safeguard National Security and Social Stability. Presented at the 14th group study session of the Political Bureau of the 18th CCP Central Committee, Beijing.

Xi Jinping. (2014c, May 25). New Approach for Asian Security and Cooperation. Presented at the Fourth Summit of the Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building Measures in Asia, Shanghai.

Xi Jinping. (2016, April 23). Keynote Speech United Work Conference on Religious Work. Presented at the United Work Conference on Religious Work, Beijing.

Xi Jinping. (2017, October 18). Address to the 19th Party Congress. Presented at the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, Beijing.

Xiang, Lanxin. (2020). The Quest for Legitimacy in Chinese Politics: A New Interpretation. New York, New York: Routledge.

Yun-Han Chu. (2013). Sources of Legitimacy and Debate over the Chinese Model. The China Review. 13(1). 1-42.

Yangqi, Tong. (2011). Morality Benevolence and Responsibility: Regime Legitimacy in China in the Past and the Present. Journal of Chinese Political Science. 16(2). 141-159.

Zhong, Yang. (1996). Legitimacy Crisis and Legitimation in China. Journal of Contemporary Asia. 26(2). 201-220.

Zhu, Leah. (2018). The Power of Relationalism in China. New York. New York: Routledge.

Written at: SOAS, University of London

Written for: Dr. Christina Maags

Date written: November 2020

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- A Well-Intentioned Curse? Securitization, Climate Governance and Its Way Forward

- The Anomaly of Democracy: Why Securitization Theory Fails to Explain January 6th

- Beyond Apocalypse: Securitization and Exceptionalism in Environmental Politics

- Neo and the ‘Hacker Paradox’: A Discussion on the Securitization of Cyberspace

- China in Africa: A Form of Neo-Colonialism?

- Analysing Chinese Foreign Policy