Over the last decades, the European Union (EU) and other international institutions (IIs) have continuously become important research objects in the field of international relations (IR) (Jørgensen, 2009, S. 188). A closer look at this trend reveals that the EU has increasingly been recognized and studied as an actor of the international system itself (Biscop & Whitman, 2013, pp. 1-2; Cremona, 2008, pp. 333-350; Cameron, 2012, pp. 1-8; Hill, Smith & Vanhoonaker, 2017, pp. 3-20; Scheffler, 2011, pp. 1- 51). However, scholars have predominantly been focusing either on the role or performance of the EU as an actor of the international system in general or its influence on other international institutions in particular (Blavoukos & Bourantonis, 2011; Drieskens & Van Schaik, 2014; Hoffmeister, 2007, pp. 41-68; Jørgensen & Laatikainen, 2013; Odermatt, Ramopoulos & Wouters, 2014, pp. 211-223). While centering most research around “[…] the bottom-up component of the interaction between international institutions and the EU […]” (Costa & Jørgensen, 2012, p.1), literature has largely overlooked the influence that international institutions might have on the EU (Kelley, 2004, pp. 425-457).

A decisive factor for the selection of the UN system as unit of analysis is the fact that the United Nations is the only International Organization (IO) with almost universal membership. As of today, the UN is composed of 193 member states (UN, n.d.). Equally significant is the increasing importance of the European Union as an actor in the UN system. The steadily growing commitment of the EU in almost all fields of activity and the associated bodies of the United Nations system is undisputed (Odermatt, Ramopoulos & Wouters, 2014; Scheffler, 2011, pp. 1-51). By strengthening its responsibilities in external relations, the EU has been advocating for deeper integration into the UN system (Odermatt, Ramopoulos & Wouters, 2014; Scheffler, 2011, pp. 1-51). As enshrined in the Treaty of Lisbon, which entered into force on 1 December 2009, the work of the EU in the UN system should be based on close cooperation (EU, 2007, Art. 10 A, Art. 188 P, Art. 2 §5). However, there is no uniform representation of the EU in the UN system. While there is no unitary representation in the Security Council (UNSC), the EU has got full representation, including the right to vote, in three UN bodies (European Council & Council of the EU, 2019; Odermatt, Ramopoulos & Wouters, 2014). In May 2011, the EU even received “enhanced observer status” in the United Nations General Assembly (UN, 2011, A/RES/65/276). The resolution marks a major step towards a more coherent representation of the interests of the EU in the UN system (Brewer, 2012, p. 182). Accumulated, the EU Member States own more than one eighth of all votes in the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) (European Council & Council of the EU, 2019). Additionally, when accumulating the contribution payments of the EU member states, the European Union proves to be the largest contributor to the UN system (Cameron, 2012, p. 1; UNGA, 2019).

Combating Terrorist Financing (CTF)

Since the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center in New York in September 2001, terrorism has become a major international security threat. In the aftermath, anti-terrorism measures have increasingly been adopted within the UN system and within the EU (Spence, 2007; Weiss & Boulden, 2004). While it has been detected that the implementation of terrorist attacks does not automatically require substantial monetary resources, the strategic organization, recruitment, training and the amplification of terrorist causes has been observed to require relatively large amounts of money (Archarya, 2009, Richard, 2005). States and international institutions therefore have a strong interest in combating terrorist financing (CTF) by interrupting the activities of potential terrorists’ efforts to obtain and generate funds (Gardner, 2007, p. 157). In this context Acharya (2009) suggests differentiating between legally and illegally funded terrorism. Legal funds are generated through non-criminal activities such as charities and donations while non-legal funds refer to the access of funds through criminal activities like illegal arms trade, money-laundering and drug and human trafficking. According to international law, illegal funds may directly be frozen or seized. Legal funds may only be subject to seizure or freezing if these financial resources are evidently intended to finance acts of terrorism (Acharya, 2009). Terrorism may be financed by both state and non-state actors (Clunan, 2007). In Directive 2005/60/EC the European Parliament and the Council define terrorist financing as ‘[…] the provision or collection of funds, by any means, directly or indirectly, with the intention that they should be used or in the knowledge that they are to be used, in full or in part, in order to carry out any of the offences within the meaning […]’ of what has been defined as terrorism[i] (EU, 2005).

The terrorist attacks of 2001 have widely been acknowledged as cause for major developments in the EU´s CTF sanctions regime. However, literature in this field observed that the CTF policy regime has substantially been influenced by guidelines and principles crafted outside the European Union (Bures, 2010, pp. 420-425; Ferreira-Pereira & Martins, 2012; Heng & McDonagh, 2008). Bures (2010, p. 422) observed that measures adopted by the EU following 9/11 “[…] were specifically designed to implement and/or enhance the aforementioned resolutions of the UN and CTF recommendations issued by the FATF[ii].”

Rationale Behind the Topic Selection

It has been decided to focus on CTF to compare the influence of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) on the EU as financial sanctions have become a core element of the European Union´s Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) (Russel, 2018). In this context, CTF policy was identified and selected as (1) there are many primary resources available to examine and analyze the impact of UNSC financial sanction of the EU´s CTF sanctions regime, such as a variety resolutions, statements and directives, which make it feasible to detect causal mechanisms of potential impact and measure the possible degree of influence; (2) in the last decades, terrorism has become an omnipresent threat to national and international security; (3) it is likely that the UNSC influences the EU`s CTF regime at least to some degree; and (4) the theoretical framework crafted and applied in the context of this paper may be used as starting point to conduct further research in this field of study.

Structure of this Paper

Firstly, an in-depth literature analysis will be used to set up the theoretical foundation and to define the (legal) concepts and terms required for the second part of this paper, in which the theoretical framework will be applied to the research question. Finally, a conclusion will be drawn to what extent the UNSC influences the EU´s financial sanctions regime to combat terrorism.

Method

Rationale for the Case Study Design

The question to what extent the UNSC influences the EU´s financial sanction regime to combat terrorism will be examined in form of a case study. “The aim of case studies is the precise description or reconstruction of a case” (Flick, 2009, pp. 143). This approach goes hand in hand with the fact that the observations made may not be compared with the results from other cases. However, this does not imperatively mitigate or weaken the meaningfulness of the results. “Because they are numerous and diverse, the predictions and observations made in a single case are not necessarily less informative than correlations calculated between a small number of causal variables and the outcomes in multiple cases” (Hall, 2008, p. 315).

For a scientific analysis of an individual case, on the one hand the case in question must be clearly delimited and defined. On the other hand, it is essential to provide a stringent justification why the case is selected for the investigation (Flick, 2009, p. 143). According to Gerring (2007, p. 17), a case in the social science sense is “a spatially delimited phenomenon (a unit) observed at a single point in time or over some period of time.” The one examined in the context of this paper is spatial in the sense of a thematic limitation in so far as it is limited to a specific policy area. The investigation is timely restricted as it makes CTF a subject of research in the period from the late 1990s, the time before 9/10, until December 2019. The end date has been chosen to incorporate the most recent data. Additionally, the case selection was influenced by the fact that the case will be analyzed based on a theoretical framework of three approaches to explain institutional influence: Historical, Rational Choice and Social Institutionalism. The case examined is therefore not representative of a population characterized by similar cases, but by its conceptual openness (Blatter & Blume, 2008, p. 346). The case is considered particularly appropriate to illustrate the worldviews of the institutional approaches to explain the causes and effects of impact exerted by international institutions and to analyze the influence of the UNSC of the EU´s CTF financial sanction regime.

Congruence Analysis

A general demarcation of congruence analysis from process analysis is daring since a large part of pertinent literature assumes congruence analysis to be an alternative approach to variable-centered covariance analysis but based on elements of process as well the congruence analysis combined (Blatter & Blume, 2008, p. 317). Process analysis addresses the complex interaction of numerous causal factors along the causal path arranged according to both temporally as well as content-wise elements of the case in question (Bennett & George, 2005, p. 140). In general, it can be said that process analysis is primarily concerned with the comprehensive understanding of a particular case, while congruence analysis is mainly interested in conclusions based on the theories applied and their characteristics (Blatter & Blume, 2008, p. 331). However, according to Blatter and Blume (2008), congruence analysis “[…] is an approach that focuses on drawing inferences from the (non-) congruence of concrete observations with specific predictions from abstract theories to the relevance or relative strength of these theories for explaining/understanding the case (s) under study” (Blatter & Blume, 2008, p. 325). For an investigation using the congruence analysis, the plurality and disparity of different explanatory approaches is therefore a mandatory requirement (Hall, 2008, p. 306).

In this paper, the approach is applied in a way that deductive hypotheses are generated as to whether and why the UNSC may exert influence over the EU´s financial sanction regime when it comes to the combat against terrorism. The hypotheses are based on the most diverse possible pattern of expected relationships between variables as well as expected causal paths (Blatter & Blume, 2008, p. 326). The core of the congruence analysis is the linking of abstract concepts and the concrete observations derived from it. This approach is justified by the assumption that there is often no “point-to-point” relationship between theory and actual observation. Therefore, the simple measurement of certain attributes of the case would only partially reflect these relations (Blatter & Blume, 2008, p. 326). The analytical framework must be developed in a way that allows an interpretation of the case based on different assumptions. Furthermore, Blatter and Blume (2008, p. 326) argue that “[…] meaningful abstract concepts often have fuzzy boundaries.” Following that, the key criterion for the indicators used to analyze this case is not their metric quality, but their concept validity as such. Haverland (2007, p. 61) defines concept validity as “[…] the requirement that the empirical indicators should capture the meaning of the theoretical concept they represent.”

The aim of this paper is to give a comprehensive insight into the case by using alternative theoretical explanatory pattern to explain institutional influence. However, this paper does not seek to derive the superiority of a single theoretical approach. The goal is rather to expose and disclose factors that may explain institutional influence in this particular case within the framework of the different theoretical approaches. “The essential characteristic of the congruence method is that the investigator begins with a theory and then attempts to assess the ability to explain or predict the outcome in a particular case” (Bennet & George, 2005, p. 181). Due to its complexity, the case examined below is not suitable for a variable-centered analysis or a consistent process analysis. In the analysis of a case whose variables are in a complex relationship to each other and thus difficult to grasp, the congruence analysis has characteristical advantages over other approaches. A case is particularly complex if the variables are theoretically consistent but cannot be transferred to a one-dimensional measuring scale. Thus, the phenomenon cannot be examined in isolation (Blatter & Blume, 2008, p. 326). In this context, Flick (2009, p. 15) argues that “[…] sometimes a clear identification and isolation of variables is not possible, so that they cannot be framed in an experimental design.“ By using congruence analysis, an attempt is made to determine the object under investigation in its entirety and to insert it into a broader theoretical context. “This makes it possible to use the full richness of information related to the empirical case to draw inferences about the relevance of theoretical concepts” (Blatter & Blume 2008, p. 327).

International Institutions as Unit of Analysis

The term “international institution” has been used to refer to a broad range of phenomena such as for International Organizations, International Regimes and International Norms (Duffield, 2007, pp. 1-7). As IIs are key analytical elements of this paper, setting up a basic theoretical foundation of the term is therefore indispensable. When comparing various definitions of the term “international institutions” some common definitional features can be identified, namely that international institutions are (1) set of practices, informal and formal rules and habits; (2) are formal organizations and/or (3) norms that (a) prescribe appropriate behavior or roles; (b) perpetuate a particular order and/or (c) serve as a basis for identity (Bull 1977, p. 71; Cox 1986, p. 219; Keohane, 1988, p. 382; Koremenos, Lipson & Snidal, 2001, p. 762; Risse, 2002, p. 605).

Institutional Influence

In the course of globalization, states have increasingly become interdependent while new actors, important non-state actors have entered the sphere of international politics. Following that, Dai and Martinez conclude that:

[…] external influence from outside the national border is ubiquitous. Such external influence takes diverse forms. The agents of the influence can be states, various non-state actors […], and international governmental rules and organizations. The mechanisms of the influence include coercion, persuasion, acculturation, and so on.

Dai and Martinez 2012, p 207

In the last decades, research has increasingly been focusing on external influence, meaning the influence exerted by international institutions. The main focus has been on the question of whether, and to what extent, international institutions affect the behavior of states (Dai & Martinez, 2012, pp. 207- 210; Karns & Mingst, 1992; Martin & Simmons, 1998, pp. 729-57). While early neoliberal institutionalists such as Keohane primarily emphasize the influence and effects of international institutions in general (Costa & Jørgensen, 2012, pp. 2-3), contemporary research has started to examine the influence that international institutions may exert on states through other non-state or on other non-state actors in general (Dai & Martinez, 2012, pp. 207- 210; Costa & Jørgensen, 2012, pp. 2-3). A key contribution to the study of influence exerted by institutions or the international system as such is associated with Gourevitch´s seminal work on the second image reverse (SIR) research (Casanova, Eliasson & Garcia-Duran, 2019, pp. 131-133; Costa, 2009, pp. 527-544; Costa & Jørgensen, 2012, pp. 2-9; Kasa, 2013, pp. 1051-1053; Zarakol, 2013, pp. 151-153). SIR research refers to Kenneth Waltz´s three images of international relations, the first image being individuals, the second one being states and the last one being the international system (Waltz, 1959). By reversing the directional logic of Waltz´s three images, Gourevitch suggests that the third image, meaning the international system, also affects the domestic structures of states. He calls this concept the second image reverse (Gourevitch, 1978).

Critical readers might assess this approach as questionable. (Neo)realist and power-based approaches emphasize the role of states, national interests and power asymmetries among states while treating international institutions as dependent variable. State interests therefore not only determine state behavior but the design and scope of IIs as well. Following this approach, realists contest that IIs may have an independent effect at all by viewing them as epiphenomenal (Carnegie, 2014, pp. 54-70; Martin & Simmons, 2005, pp. 192- 212; Mitchell, 2009, pp. 66-84). Nonetheless, excluding the potential influence of IIs from research assumptions and hypotheses leads to a lack important factors influencing the dynamics and processes in the international system. Defective scientific deduction may occur when ignoring the actorness of IIs within the international system, taking into account that IIs have firmly arrived in the system of global governance (Dekker & Wessel, 2004, pp. 215-236; Keohane, 1998, pp. 82-96; Stephen & Zürn, 2010, pp. 91-101) and are even perceived as autonomous actors (Collins & White, 2011; Cooper, Hawkins, Jacoby & Nielson, 2008, pp. 501-524; Mathiason, 2007). Coming back to the European Union and considering its active participation and profound integration into the international system, no logical reasons can be found to assume that the EU will not be influenced by IIs (Costa & Jørgensen, 2012, pp. 2-3; Gehring & Oberthür, 2006, pp. 1-19; Gehring & Oberthür, 2009, pp. 125–156; Jørgensen & Wessel, 2011, pp. 261-286).

Causal Mechanisms of Influence

When analyzing the influence of international institutions, the causal mechanisms of influence are to be identified in the first place (Costa & Jørgensen, 2012, p.3). Costa and Jørgensen set up an important guideline when investigating the influence of an II on the EU:

According to the SIR literature, [IIs] exert their influence by improving the chances for success of policy entrepreneurs supporting them. […] [T]he basic mechanism is altering the “domestic balance” (Dai, 2005, p. 388). This alteration may involve (1) providing opportunities or constraints to actors; (2) changing their ability to influence decision making by changing the distribution of power; (3) establishing or spreading norms and rules; and (4) create path-dependencies.

Costa and Jørgensen 2012, p 3.

As already pointed out by Dai, “[…] the basic mechanism [of influence] is altering the “domestic balance” (2005, p. 388). In our case, the domestic balance is considered the balance at the EU-level. Logically, the paper is concerned with the analysis of potential changes occurring within the CTF sanction regime of the EU caused by UNSC sanctions. The causal mechanisms mentioned in quote above can be assigned to and explained with three different theoretical approaches -rationalist-, sociological- and historical-institutionalism- each highlighting different channels through which IIs may exert influence (Costa & Jørgensen, 2012, pp. 3-5). Costa & Jørgensen argue that these approaches are suitable as they can explain different forms of influence that IIs may exert over the EU (2012, p. 5). Jupille, Caporaso and Checkel (2003, p. 16) define these approaches as “[…] problem-driven, empirically oriented perspective […]” to obtain more comprehensive results about causal mechanisms.

On the one hand, Rational Choice Institutionalism (RCI) argues that states set up IIs to maximize their own preferences while seeking to reduce the transaction costs of collective actions which would be substantially higher without IIs. However, states encounter rule-based constraints but also opportunities that shape and change state behavior. IIs thus change the behavior of states through an incentive-based approach (Hall & Taylor, 1996, pp. 936-957; Olson, 1971, pp. 53-60). Recent RCI literature put a stronger emphasis on “[…] how [IIs] shape the motivations of the often-competing domestic interests who on turn shape the incentives of the governmental decision makers” (Dai & Martinez, 2012, p. 213). Following, the author arrives at a first hypothesis:

H1: The more the UNSC exhibits incentive structures, the stronger the change it may cause and thus the influence it may exert on the EU´s CTF financial sanction regime.

On the other hand, Sociological Institutionalism (SI) suggests that by defining “[…] meanings, norms of good behavior, the nature of social actors, and categories of legitimate social action in the world” (Barnett & Finnemore, 2004, p. 7). SI establishes new intersubjectively agreed upon preferences, interests and socially accepted behavior while setting up new common task for states in the international system (Barnett & Finnemore, 2004, pp. 3-4; Hall & Taylor, 1996, pp. 936-957; Johnston, 2001, p. 502). Through processes of persuasion, social influence and group pressure, SI suggests that IIs can change state behavior beyond the alteration of strategies towards the modification of their underlying preferences (Dai & Martinez, 2012, p. 213). Thus, the author hypothsizes:

H2: The more the UNSC creates and amplifies norms and rules through processes of persuasion, social influence or group pressure, the stronger the change it may cause and thus the influence it may exert on the EU´s CTF financial sanction regime.

Lastly, Historical Institutionalism (HI) “[…] draw[s] on both the consequentialist [RCI] and sociological [SI] logics […]” (Costa & Jørgensen, 2012, pp. 3-5) and defines IIs as “[…] humanly devised constraints that structure political, economic, and social interaction” (North, 1991, p. 97). Institutions are determined by and produced of history, while determining the conditions for activities in the future and “[…] limit the scope of what is possible” (Aspinwall & Schneider, 2000, p. 16), which generates path-dependencies that in turn affect future activities (Hall & Taylor, 1996, pp. 936-957). Against this backdrop, a third hypothesis can be constructed:

H3: The more UNSC creates path-dependencies and historical dependence, the stronger the change it may cause and thus the influence it may exert on the EU´s CTF financial sanction regime.

Institutional Variations and their Impact on Influence

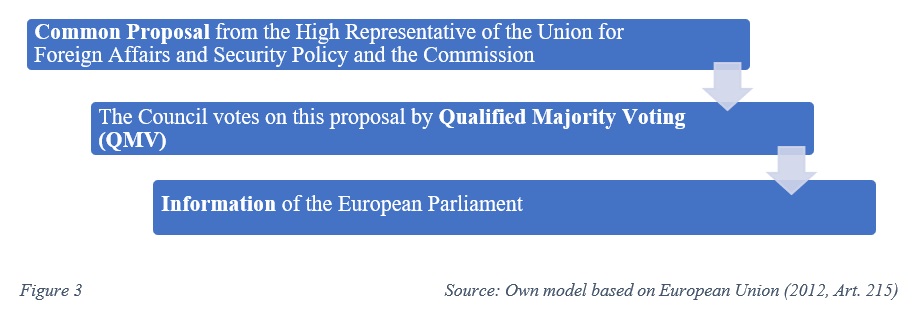

It is also important not to lose sight of the settings within the EU and its several institutions and decision-making procedures. The European Union is a complex system with “[…] no central agenda-setting and coordinating actor” (Hix, 1998, p. 39). For the purpose of the examination of influence of international institutions on the EU, the voting-mechanisms within the different EU-institutions regarding the adoption of decisions stemming from IIs are relevant. Dai and Martinez (2012, p. 214) suggest the following categorization for voting methods used within EU-institutions for the adoption II policies: “(1) intergovernmental method or unanimity in the Council, (2) informal governance mechanisms, and (3) community method or Qualified Majority Voting in the Council.” Tseblis (2000) concludes that the higher the number of actors entitled to veto decisions, the lower the likelihood that international institutions have an influence on the EU. Within the EU, two competing voting procedures can be identified, namely the unanimity and the Qualified Majority Voting (QMV). The former being defined by highly decentralized decision-making and a high number of member states able to block decisions. Subsequently, policies decided on via unanimity are less inclined to be influenced by international institutions (Drüner, Klüver, Mastenbroek et al., 2018). Thus, the author hyposizes:

H4: The less decisions are being made according to unanimity voting and the more decisions are being made based upon majority voting, the more the EU is susceptible to change and thus to be influenced by the UNSC.

Analytical Indicators

This chapter pursues to set up the indicators, against which the hypotheses the author arrived at in the preceding chapters will be tested. A summary of all hypothesis and their affiliated indicators is listed in a table at the end of this chapter (cf. Annex 14.1). The first three hypotheses will be tested using the same indicators to analyze, which of the three different institutional approaches may explain institutional influence in this case best. With different indicators applied for each approach, an objective conclusion would not be feasible. The first indicator used, will be how the EU´s CTF financial sanction system has changed within the period starting shortly before 9/11 and ending at 31. December 2019. The author defines ‘changes’ as deviations from a particular status quo occurring within a certain, pre-determined period consisting of a clear starting point, the status quo, and an endpoint. A focus will lie on the development of the regime after the terroristic attacks, including the factors that influenced these potential developments. It is important to measure to what extent changes in the EU´s financial sanction regime occurred, and which factors have been influencing certain steps of the development of the regime as we know it today. The results will be arranged according to the following attributes: high, medium, low. The second indicator will be the analysis of resemblances, respectively differences between both the UN´s and the EU´s CTF sanctions regime. This is important, as it is possible to see whether, and if yes which, institutional patterns and designs were imitated, adapted or newly developed. Again, the results will be arranged according to the following attributes: high, medium, low. The third indicator seeks to investigate whether the EU adopted UNSC resolutions (UNSCRs). This is especially interesting when considering that the EU, as a non-member of the UN, is not legally obliged to adopt UNSCRs. Therefore, the results will be arranged according to the following criteria: no adoption, adoption with changes and literal adoption. Subsequently, this indicator will be supplemented by an analysis to what degree the EU implements UNSCRs concerning CTF. The fifth hypothesis will be tested by digging deeper into the legal liabilities arising from UNSCRs for the European Union as international institution and how the results fit into the EU´s behavior in this regard. Here as well, the results will be arranged utilizing the following attributes: high, medium, low. The last hypothesis will be examined by depicting the decision-making procedure of the European Union when it comes to the adoption of CTF sanctions. Here, the following attributes will be used: unanimity in the Council, informal governance mechanisms, QMV and mixed form of the three preceding indicators. The indicators will be applied empirically by analyzing existing research, UNSCRs, EU´s sanctions, positions and comments. Furthermore, the EU Sanctions Map[iii] will be used as a source to analyze the character and origin of EU CTF sanctions.

Measurement of Influence

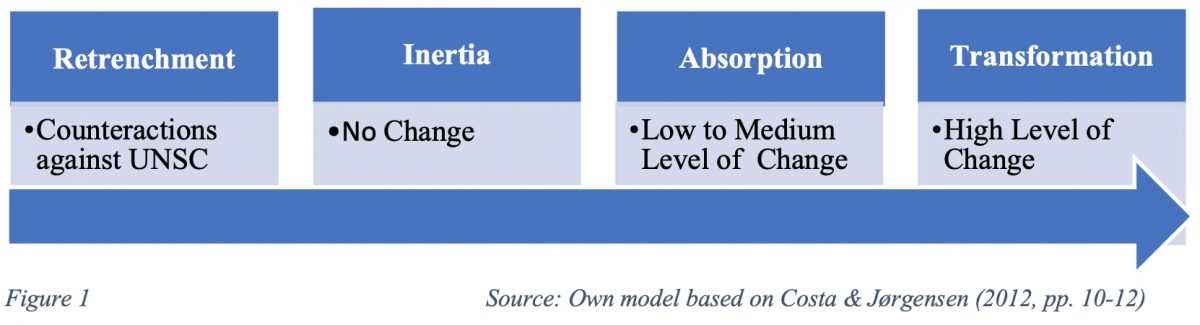

Costa & Jørgensen refer to SIR literature originating from Börzel and Risse (2000, 2003), Radiaelli (2000, 2002) and Lendschow (2006) when proposing four classifications to measure influence, namely inertia, absorption, transformation and retrenchment (2012, p. 11). The authors assess these classifications as especially appropriate as “[…] they cover all possible magnitudes and directions of change and [are] comprehensive enough to include different sorts of change” (Costa & Jørgensen, 2012, p. 11). Retrenchment refers to cases in which the European Union deliberately acts against the respective international institution. In situations of retrenchment, the direction of change is one of increased disintegration from and counteractions against the II in question (Radealli, 2000, p. 37). It is assumed that “[…] the domestic actor(s) that endorses the policy changes derived from it to be weakened or perhaps even ostracized by other actors” (Costa & Jørgensen, 2012, p. 12). Inertia means, that the respective international institution is not able to exert any kind of influence. It would apply if the European Union would not be affected by any decision taken in the UN and thus no change within the EU and its Member States can be observed (Radealli, 2000, p. 37). More precisely, “[…] policies and norms derived from the II are not endorsed by any domestic actor, or alternatively the latter is only able to build weak coalitions with nor or very little impact” (Costa & Jørgensen, 2012, p. 11). In the long run, inertia might become impossible to be sustained either economically, as it may become too costly, or politically, as it may be judged as unsuitable (Costa & Jørgensen, 2012, p. 11; Radealli, 2000, p. 37). There is a high risk that long periods of inertia are followed by crises or shocks (Radealli, 2000, p. 37). Thirdly, absorption indicates that the international institution in question has some degree of influence on the EU (Costa & Jørgensen, 2012, p. 11). Héritier elucidates absorption by referring to it as an adjustment to policy requirements without real modification of the essential structures and changes in the ‘logic’ of political conduct (2001, pp. 53-59). It means that the influence of the respective II does not affect “[…] the correlation of forces among member states, between them and EU institutions, or among the latter, as well as policy paradigms […]” (Costa & Jørgensen, 2012, p. 11). Nonetheless, absorption may also create chances and opportunities for the EU to gain new abilities to approach specific issues (Radealli, 2000, p. 37). Lastly, transformation refers to a high degree of influence exerted by the respective international institution on the EU. It leads to changes in policies and policy-making procedures (Costa & Jørgensen, 2012, p. 11) followed by changes in the ‘logic’ of political conduct (Börzel & Risse, 2000, p. 10). The changes considerably affect “[…] the distribution of power within the EU, the emergence of dedicated administrative units, working groups, committees or networks, or the creation of specific bureaucratic routines” (Costa & Jørgensen, 2012, p. 11). Important to mention in that regard is, as in case of transformation, the EU is assumed to acquire more competencies and capabilities to approach specific issues on internal and international level (Costa & Jørgensen, 2012, p. 11).

Case Study

Legal Background and the EU´s Commitment to International Law

The UNSC´s principal mandate is the maintenance of international peace and security (UN, 1945, Art. 24 §1). To achieve this, Chapter VII of the UN Charter transfers significant powers to the UNSC, including the capability to adopt sanctions. In this regard, Article 41 states that:

[t]he Security Council may decide what measures not involving the use of armed force are to be employed to give effect to its decisions, and it may call upon the Members of the United Nations to apply such measures. These may include complete or partial interruption of economic relations and of rail, sea, air, postal, telegraphic, radio, and other means of communication, and the severance of diplomatic relations.

UN, 1945, Art. 41

Pursuant to this provision, member states of the United Nations are obliged to implement the decisions taken and to mutually support each other in doing so (UN, 1945, Art. 25, 48 & 49). Successful adoption of sanctions requires the approval of at least seven members of the UNSC including the five permanent members and excluding the respective parties to a conflict, if represented in the UNSC (UN, 1945, Art. 27 §3). The 50[iv] founding members of the UN delegated enormous power to the UNSC as it is the only organ of an international institution that can pass resolutions that impose legal obligations upon all member states (Hurd, 2002). As the EU is not a member state of the UN, it is neither bound by the provisions enshrined in the UN Charter nor by UNSCRs. Only the EU member states as separate units, respectively member states are thus bound by both the UN Charter and UNSCRs. However, EU commits itself to the provisions of the UN Charter by enshrining Article 10 a (1) into the Treaty of Lisbon:

[t]he Union’s action on the international scene shall be guided by the principles which have inspired its own creation, development and enlargement, and which it seeks to advance in the wider world: democracy, the rule of law, the universality and indivisibility of human rights and fundamental freedoms, respect for human dignity, the principles of equality and solidarity, and respect for the principles of the United Nations Charter and international law.

EU, 2007, Art. 10 a §1

Additionally, in a declaration concerning the CSFP the EU member states stress:

[…] that the European Union and its Member States will remain bound by the provisions of the Charter of the United Nations and, in particular, by the primary responsibility of the Security Council and of its Members for the maintenance of international peace and security.

EU, 2007, 13th Declaration

In that regard, the EU pledges itself to the implementation of UNSCRs and even states that “[i]t is important that the EU implements such UN restrictive measures as quickly as possible” (Council of the EU, 2018, para 38). However, even though the EU is strongly committed to perpetuating the international legal order, they may act beyond UNSCRs. This was embedded in the EU´s Guidelines on Implementation and Evaluation of Restrictive Measures:

Certain restrictive measures are imposed by the Council in implementation of Resolutions adopted by the [UNSC] under Chapter VII of the UN Charter. In the case of measures implementing UN SC Resolutions, the EU legal instruments will need to adhere to those Resolutions. However, it is understood that the EU may decide to apply measures that are more restrictive.

Council of the EU, 2018, para 3

In other words, the EU reserves it right to adopt additional or stricter sanctions if deemed necessary.

Current CTF Sanctions at EU Level

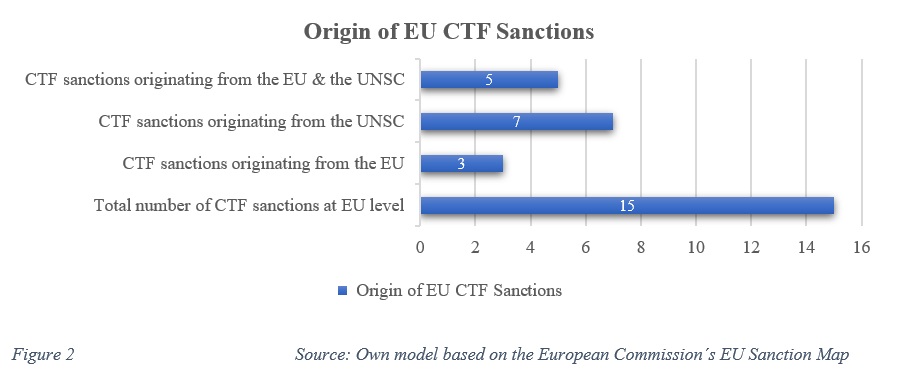

In chapter 9.1, it has already been pointed out that the EU not only fully adopts and implements UNSCRs, but they also impose (additional) sanctions on its own. While the EU reserves itself the right to enact sanctions programs independently, it seems to be particularly exciting to have a closer look on the separate sanction programs constituting the EU´s current CTF sanction regime. The EU Sanction Map has been examined according to the following questions: (1) Which current sanctions programs match the EU´s definition of terrorism? (cf. Chapter 1.1 Combating Terrorist Financing (CTF)) (2) Which sanctions programs include financial sanctions (i.e. asset freeze and prohibition to make funds available)? In cases where the level of available information was assessed insufficient, UNSCRs were utilized to complement the examination. The table with the entire investigation can found in the annex of this paper (cf. Annex 14.2). Overall, 15 actual CTF sanctions programs have been observed that fulfill both criteria. These 15 sanctions were the subjects to further examination. 7 sanctions programs implementing UNSCRs. In further 5 cases the EU applies own additional sanctions along with UNSC sanctions. Finally, the EU has currently 3 autonomous CTF sanctions programs (Figure 2). This means that in the context of 8 current CTF sanctions programs, the EU applies at least to some degree autonomous measures independently from UNSC sanctions. In other words, in more than a half CTF sanctions programs the EU acts beyond UNSCRs as part of ther CFSP.

Mechanism of CTF Sanction Adoption

In areas in which the EU possesses the exclusive legislative competences, such as commercial policy and the operation of the internal market, sanctions are implemented by secondary legislation, more precisely the adoption of a Council legislation. Sanctions that fall within this specified range include trade relations with non-EU member states and all varieties of economic and financial sanctions (European Council & Council of the EU, 2019; Cornell, Gordon & Smith, 2019, p. 38). Article 215 TFEU specifies this procedure (Figure 1):

1. Where a decision […] provides for the interruption or reduction, in part or completely, of economic and financial relations with one or more third countries, the Council, acting by a qualified majority on a joint proposal from the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and the Commission, shall adopt the necessary measures. It shall inform the European Parliament thereof. 2. Where a decision adopted in accordance with Chapter 2 of Title V of the Treaty on European Union so provides, the Council may adopt restrictive measures under the procedure referred to in paragraph 1 against natural or legal persons and groups or non-State entities.

EU, 2012, Art. 215

The Development of the EU´s CTF Sanction Regime

The EU´s counter terrorism policies may be retraced to the Terrorisme, Radicalisme, Extrémisme et Violence Internationale Group (TREVI Group), an intergovernmental network discussing issues regarding cross-national terrorism, radicalism, extremism and violence. However, CTF sanction measures had not been adopted during that time (Kaunert & Léonard, 2012). Only the 9/11 terrorist attacks “[…] triggered the perception of the terrorist threat as global and borderless” (European Parliament, 2019, p. 4). In that sense, the attacks can be seen as ‘critical junctures’ leading to a considerable development of EU counterterrorism measures in general and the CTF sanction regime in particular (Argomaniz, Bures & Kaunert, 2015; Bossong, 2013, pp. 38-58; Gregory, 2005; Peers, 2003; Zimmermann, 2006). At an extracurricular Council meeting on 21 September 2001, terrorism has been acknowledged as major threat to the EU´s security. An action plan was adopted to immediately react to the threat exerted by international terrorism, including the combat against terrorist financing as an ‘decisive aspect’ (European Council, 2001a; European Council, 2001b, 2). In that regard, the Council called:

[…] upon the ECOFIN and Justice and Home Affairs Councils to take the necessary measures to combat any form of financing for terrorist activities, in particular by adopting in the weeks to come the extension of the Directive on money laundering and the framework Decision on freezing assets.

European Council, 2001b, 5

In addition, the EU member states were invoked to urgently sign and ratify the United Nations Convention for the Suppression of the Financing of Terrorism (European Council, 2001b, 5). Supplementary, an Anti-Terrorism Roadmap was adopted consisting of 46 measures including 2 against terroristic financing (European Council, 2001c). “With 431 votes in favor, 45 in opposition, and 24 abstentions on 4 October, the Extraordinary EU Council counterterrorism measures were given a ringing endorsement by a parliamentary ‘ratification’” (Zimmermann, 2006, p. 127). In 2004, the EU Plan of Action on Combating Terrorism was adopted. Along with measures to curb terrorism, an extensive ‘progress-review-process’ was included “[…] to safeguard the swift and even implementation of counterterrorism measures discussed on the EU level” (Zimmermann, 2006, p. 127). This ‘progress-review-process’ can be compared to the monitoring and ‘naming and shaming’ measures of the UNSCR 1373 Counterterrorism Committee to ensure compliance (Zimmermann, 2006, pp. 127-128). In December 2004, the European Council adopted a Strategy with the goal of combatting terrorist financing (Kaunert & Léonard, 2012). In 2008, the Strategy on Terrorist Financing was extensively revised and advanced as “[t]errorist finance threats change constantly, and vary greatly across customers, jurisdictions, products, delivery channels, as well as over time” (Council of the EU, 2008, p. 2). Since then, the CTF sanction regime respectively its legal framework has steadily been revised, developed and strengthened. In the European Commission´s Agenda on Security the importance of CTF measures was named a one of the major instruments to effectively tackle terrorism (European Commission, 2015). The Directive on Combatting Terrorism provides an extensive definition obliges member states to:

[…] take the necessary measures to ensure that providing or collecting funds, by any means, directly or indirectly, with the intention that they be used, or in the knowledge that they are to be used, in full or in part, to commit, or to contribute to the commission of, any of the offences referred to in Articles 3 to 10 is punishable as a criminal offence when committed intentionally.

EU, 2017, Directive 2017/541, Art. 11

The Fifth Anti-Money Laundering Directive “[…] aims to prevent the use of the Union’s financial system for the purposes of money laundering and terrorist financing” (EU, 2015, Directive 2015/849). In 2018, a new regulation entered into force strengthening existing regulations and protection mechanisms against illicit cash movements that “[…] foster criminal and terrorist activities which endanger the security of citizens of the Union” (EU, 2018, Regulation 2018/1672). This is of course not an exclusive list of developments within the legal framework of the CTF sanction regime, but it illustrates the extensive evolution and advancement of a policy field which has been established from scratch in the aftermath of 9/11. Subsequently, a high level of change can be observed in the period before 9/11 and after. Looking at the dynamics in the last 19 years, there is little doubt that this policy will be further growing in the future. The CTF sanction regime has established itself as an important integral part of the EU´s CFSP.

Factors of Influence

Two major factors of influence of the UNSC of the EU´s CTF sanctions regime have been detected. A first major observation by Kaunert and Léonard (2012) is the EU´s ‘path-dependency’ on earlier EU sanctions regimes that have been used to put UNSCRs into practice. King, Peters & King (2005) define ‘path-dependency’ as “[…] self-reinforcing processes in institutions that make institutional configurations, and hence their policies, difficult to change once a pattern has been established.” International institutions thus have a propensity to reiterate structures and settings which make it difficult for them to achieve change. Applying this definition to the present case, it means that the EU had developed proceedings on how to implement UNSCRs at EU-level against states which are now used to impose economic sanctions against terrorist suspects, meaning mainly individuals or entities (Eling, 2007; Gutierrez-Fons & Tridimas, 2008; Kaunert & Léonard, 2012;Vlcek,2009). Eling specifies this approach by stating that “[for] the EU, effective implementation of [UNSCRs] imposing restrictive measures is an article of faith, predating 9/11 and, indeed, independent of whether a resolution targets terrorist suspects or say, individuals impeding the peace process in Côte d´Ivoire” (Eling, 2007, p. 114). The procedures regarding the implementation of UNSC economic sanctions through the adoption of regulations at the then European Community level has established itself in the 1990s. Before, during the Cold War, sanctions were hardly adopted, and if a sanction passed their way through the UNSC they were exhortative and weak (Elliott, 2010). The first being the implemented UNSC economic sanctions against the Iraq by adopting Regulation 2340/9020 and, later Regulation 3155/90.21 (Pavoni, 1999, p. 587). Another example refers to economic sanctions adopted against Libya. Based on UNSCR 748(1992), the European Community enacted Regulation 945/92 (Pavoni, 1999, p. 587).

The way the EU proceeds with the CTF sanction regime does not deviate from the procedure related to other sanction regimes. While former sanctions exclusively addressed states, the CTF sanctions mainly address non-states actors (Eling, 2007; Gutierrez-Fons & Tridimas, 2008; Kaunert & Léonard, 2012; Vlcek,2009). A second factor of influence to be observed is the EU´s strong desire to uphold and boost both the (international) norms of multilateralism and rules of international law reinforced through social influence and group pressure exerted by the international significance and meaningfulness of the UNSC and the resolutions it passes. (de Búrca, 2010; Della Giovanna & Kaunert, 2010; Kaunert & Léonard, 2012; Manners, 2002; Manners & Whitman, 2003). This has repeatedly been stated by the European Union, actually four times in the Treaty of Lisbon (EU, 2007, Art. 10 A §1, Art. 10 A §2 (h), Art. 20 D §1(b), Art. 116a §4 (a); Eling, 2007; Kaunert & Léonard, 2012). The European Security Strategy, which was adopted in 2003 by the European Council, it was expressed that the EU is “[…] committed to upholding and developing International Law” (EU, 2003, p. 9).

Additionally, the importance of an “[…] effective multilateral system” was emphasized, while the “[s]trengthening [of] the United Nations, equipping it to fulfil its responsibilities and to act effectively, is a European priority” (EU, 2003, p. 9). The Strategy was meant to set out the EU´s security objectives and its policy implications on its CFSP and is thus an important political document which received extensive attention internationally. It is still used as reference for the direction of the EU´s CFSP (Kaunert & Léonard, 2012). Furthermore, the EU strongly pursues to project and reflect its commitment to and prioritization of multilateralism and international law. The EU wants to be perceived as the ‘proper/good implementer’ of international law and multilateral cooperation and effectiveness (de Búrca, 2010; Della Giovanna & Kaunert, 2010; Kaunert & Léonard, 2012; Manners, 2002; Manners & Whitman, 2003). It therefore becomes self-evident that the EU continues to reproduce its policy agenda and extends it to CTF sanctions as well.

The Role of the EU Courts Regarding the Implementation of UNSCRs at EU Level

In 2008, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) ruled in the case Kadi and Al Barakaat International Foundation v Council and Commission that there is no legal difference between financial sanctions adopted independently from UNSCRs and those adopted following an UNSCR (ECJ, 2008, Case C-402/05 & C-415/05). However, not less important to mention is the generally more critical perception of the ECJ regarding the adoption and implementation of UNSCRs on EU level. The above cited cases followed a rather contested rulings passed by the EU´s Court of First Instance (CFI) in 2005 (Kaunert & Léonard, 2012, pp. 123-128).

While it is not possible to cover the details of the cases in this paper in length, some main points for the examination of the research questions are briefly outlined here. The background of both rulings was that Kadi and Al Barakaat International Foundations have been placed on the EU´s financial sanction list as they were included on the 1267 Committee list consisting of suspected terrorists. This Committee has been established pursuant to some UNSCRs “[…] concerning ISIL (Da’esh), Al-Qaida, and associated individuals groups undertakings and entities” (UNSC, n.d.). Firstly, both courts ruled that the EU has the legal competences to adopt CTF sanctions against individuals and entities charged terrorist activities. Kaunert and Léonard (2012, pp. 123-128) assess this ruling to be ‘significant’. If the courts would not have adjudicated the EU as competent, the CTF sanctions in that regard would have been abolished. UNSCRs would then have to be implemented by the member states separately and not collectively at EU level (Kaunert & Léonard, 2012, pp. 123-128). Consequently, the direct effects of UNSCRs on the EU would have been diminished. Secondly, the CFI ruled that the legal review of CTF sanctions originating from UNSCRs lies beyond its judicial competences as “[…] instruments adopted by the EU to give effect to UNSCRs would amount to an evaluation of the UN lists of terrorist suspects […]” (Kaunert & Léonard, 2012, p. 125). The CFI thus acknowledged the superiority of UNSCRs as source of international law. After major criticism on this ruling, the ECJ adjudicated in the case Kadi and Al Barakaat International Foundation v Council and Commission that the EU courts indeed have the judicial competences to decide whether EU sanctions are in conformity with EU law, emphasizing the “[…] autonomy of the Community´s legal order vis-á-vis the international order” (ECJ, 2008, Case C-402/05 & C-415/05, Kaunert & Léonard, 2012, p. 125). However, this ruling has been subject to a lot criticism among legal scholars regarding the relationship between international legal order and EU law. It has been argued that the ruling reduces assertiveness and significance of the implementation of UNSCRs as significant sanctioning mechanism of internal law (de Búrca, 2010). De Búrca (2010) concludes that regarding the EU´s CTF sanction regime, future rulings are expected to come. They might change these relational dynamics between UNSC and EU.

Explaining the Influence of the UNSC over the EU’s CTF Sanction Regime

This paper has argued that two main influential factors elucidate how the UNSCs affects the EU´s CTF sanction regime: (1) path-dependency from previous sanctions programs against states, which are no applied in the context of CTF sanctions against non-state actors, and (2) the EU´s consistently declared commitment to the norms and values of multilateralism and the rules of international law reproduced and reinforced through the internationally legally binding nature of UNSCRs. While the former argumentation proves hypothesis 3 to be true, the latter confirms the applicability of hypothesis 2 in the context of this case study. On the one hand, historical institutionalism explains that path-dependency caused the EU to use traditional sanction measures that had formerly been employed against states now against non-state actors to combat terrorist financing.

On the other hand, sociological institutionalism explains how the creation and amplification of norms and rules of the UNSC led the EU to pursue to appear as the ‘good’ or ‘ideal’ implementer of UNSCRs. H2 and H3 have been tested to have considerable influence on the development and the state of being of the EU´s CTF sanction regime. The high influence of the UNSC manifests itself in the EU´s adoption and implementation patterns. Referring to this, the degree to which the EU implements UNSCRs may be assessed as high. Even though international law does not bind the EU as a regional organization to adhere to UNSCRs, it commits itself to the adoption and implementation of the latter. While the obligations arising from UNSCRs legally apply only to UN member states, the EU even pledges to implement them as rapidly as possible in their full extent. In effect, the EU adopts all UNSCRs without changing the wording of their content. These are all arguments for a great influence of the UNSC on the EU. Nonetheless, the EU may impose autonomous sanctions beyond UNSCRs or additional sanctions if SC sanctions are assessed insufficient. This means that in the context of current CTF sanctions programs, the EU applies in 8 cases at least to some degree autonomous measures independently from UNSC sanctions. In over a half of its CTF sanctions programs the EU acts beyond UNSC measures.

Coming to hypothesis 1, which could not have been proven to explain the existence of influence of the UNSC. As a non-member of the UN, the UNSC has simply no capacities to exhibit enough incentives to lead the EU to adhere to the UNSCRs or to change their character. Nonetheless, this should not undermine the ability of rational choice institutionalism to explain potential influence structures of particular international institutions on the EU or other IIs at all. It is simply not applicable to this case.

Hypothesis 4 assumes that policy areas decided on via QMV are more susceptible to change and thus to be influenced by the UNSC. The assumption is supported by the fact that it would have been irrational to use another voting method and to increase the risk of a CTF secondary legislation to be vetoed. The EU has an interest in adopting and implementing UNSCRs to assure in areas where the EU has exclusive competences, EU legislation does not contradict the international legal obligations of its member states (Della Giovanne & Kaunert, 2010). However, it is difficult to empirically prove the direct causal relationship between the QMV and the susceptibility of the EU to change. With the EU having consistently committed itself to international law and its declared adherence to UNSCRs, the consistent implementation and adoption of UNSCRs could have been realized with unanimity or informal governance mechanisms either way. All EU member states are simultaneously UN member states; thus, they are obliged to adhere to UNSCRs anyways. The argumentation made here do not diminish the influence of the UNSC on the EU, it rather proves it. Although it is not necessarily due to the QMV. Nevertheless, in a historical but highly criticized ruling of the ECJ, the influence of the UNSC was slightly diminished by emphasizing the autonomy of the EU´s legal system vis-á-vis the international legal system. However, further judgments on the EU´s CTF sanction regime are highly expected to come. Which may then change the currently high degree of influence of the UNSC.

Measuring the Influence of the UNSC over the EU´s CTF Sanction Regime

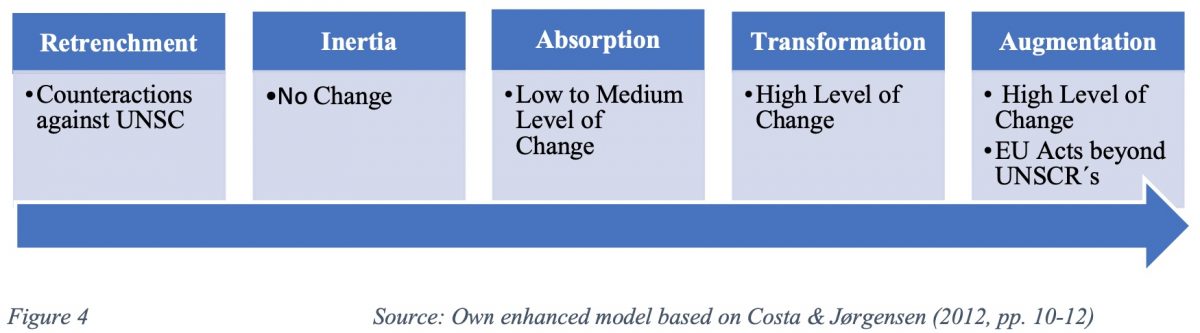

With reference to chapter 7 of this paper, the last step would now be to categorize the overall influence the UNSC on the EU´s financial sanction regime to combat terrorism. The concepts refer to influence as to the degree of change an II exerts on the EU. Four classifications have been proposed to do so, namely inertia, absorption, transformation and retrenchment. However, none of them appropriately depict the influential relationship between both the UNSC and the EU´s CTF sanction regime. In the concept, the highest degree of influence would be classified through transformation. Yet, it does not account for cases in which the EU acts in tradition of but beyond the international institution in question. In cases in which the UNSC does not adopt or is not able to agree upon sanctions but the EU considers sanctions necessary, the EU may adopt restrictive measures autonomously. The same applies to situations in which the EU assesses UNSC sanctions as being not restrictive enough, the EU may adopt sanctions independently. This behavior is not against the international institution in question (retrenchment), it rather should complement the UNSC work where it is for example blocked by a veto power to safeguard international peace and security. Therefore, a fifth mechanism has been devised: augmentation. Augmentation means a process in which an international institution has significant influence over the EU leading to a high degree of change in policies and policy-making procedures which is followed by changes in the ‘logic’ of political conduct. Additionally, the EU acts beyond the provisions and mechanisms of the international institution in question. It does so not to harm or to act against the respective II, but to complement the achievement of the respective institutions overall goal, which is in our case the protection and maintenance of international peace and security (Figure 4).

Conclusion

This research has investigated the influence exerted by the UNSC over the development and the status quo of the EU´s CTF sanction regime. Even though the EU is not legally bound to adopt and implement UNSCRs, it consistently does so. It has revealed that the former exercise a high degree of influence over the latter, mainly caused by two factors (1) path-dependency and, (2) the EU´s strong commitments to the norms of multilateralism and the rules of international law. Furthermore, the research results contribute to the existing literature insofar as a new indicator to measure the influence of international institutions on the EU has been detected: augmentation. However, it could not have been proved whether QMV makes the EU more susceptible to change. The investigation of the causal relationship between chance susceptibility and voting procedures may be covered by future research by using process-tracing as a method. Although, this paper has shown the currently high degree of influence of the UNSC on the EU´s CTF sanctions programs, it has pointed out to the role and more critical stand of the EU´s courts. With further judgments to come, the level of influence may be subject to change in the future. Conscious investigation of the future rulings of the courts are a necessary prerequisite to investigate whether, and if yes to what extent, the high influence of the UNSC may be challenged.

Figures

Annexes (download here, pdf)

Bibliography

Acharya, A. (2009) Targeting Terrorist Financing: International Cooperation and New Regimes. London: Routledge.

Argomaniz, J., Bures, O. & Kaunert, C. (2015) A Decade of EU Counter-Terrorism and Intelligence: A Critical Assessment. In: Intelligence and National Security, 30(2-3), pp. 191-206.

Aspinwall, M. D. & Schneider, G. (2000) Same Menu, Separate Tables: The Institutionalist Turn in Political Science and the Study of European Integration. In: European Journal of Political Research, 38, pp. 1-36.

Barnett, M. & Finnemore, M. (2004) Rules for the World. International Organizations in Global Politics. Ithaca & London: Cornell University Press.

Bennet, A. & George, A. (2005) Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences. Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press.

Biscop, S. & Whitman R. G. (Eds.) (2013) Introduction. In: The Routledge Handbook of European Security. Abingdon & New York: Routledge, pp. 1-2.

Blatter, J. & Blume, T. (2008) In Search of Co-variance, Causal Mechanisms or Congruence? Towards a Plural Understanding of Case Studies. In. Swiss Political Science Review, 14(2) pp. 115-156.

Blavoukos, S. & Bourantonis, D. (Eds.) (2011) The EU Presence in International Organizations. London: Routledge.

Bossong, R. (2013) The EU´s Reaction to 9/11. In: Bossong, R. (Ed.) The Evolution of EU Counter-Terrorism: European Security Policy After 9/11. Abingdon & New York: Routledge, pp. 38-58.

Börzel, T. A. & Risse, T. (2000) When Europe Hits Home: Europeanization and Domestic Change. In: European Integration online Papers (EIoP), 4(15). Available at: >http://eiop.or.at/eiop/texte/2000-015a.htm< [Accessed: 06.01.2020].

Brewer, E. (2012) The Participation of the European Union in the Work of the United Nations: Evolving to Reflect the New Realities of Regional Organizations. In: International Organizations Law Review, 9 (2), pp. 181-225.

Bull, H. (2012) The Anarchical Society: A Study of Order in World Politics. 4th ed. London: Red Globe Press.

Bures, O. (2010) EU’s Fight Against Terrorist Finances: Internal Shortcomings and Unsuitable External Models. In: Terrorism and Political Violence, 22(3), pp. 418-437.

Cameron, F. (2012) An Introduction to European Foreign Policy. 2nd ed., Abingdon & New York: Routledge, pp. 1-8.

Carnegie, A. (2014) States Held Hostage: Political Hold-Up Problems and the Effects of International Institutions. In: American Political Science Review, 108(1), pp. 54-70.

Caporaso, J. A., Checkel, J. T. & Jupille, J. (2003) Integrating Institutions: Rationalism, Constructivism, and the Study of the European Union. In: Comparative Political Studies, 36(1-2), pp. 7-40.

Casanova, M., Eliasson, L. J. & Garcia-Duran, P. (2019) International Institutions and Domestic Policy: Assessing the Influence of Multilateral Pressure on the European Union’s Agricultural Policy. In: Journal of European Integration, 42(2), pp. 131-146.

Clunan, A. L. (2007) U.S. and International Responses to Terrorist Financing. In: Giraldo, J. K. & Trinkunas, H. A. (Eds.) Terrorism Financing and State Response. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Collins R. & White N.D. (2011) (Eds.), International Organizations and the Idea of Autonomy: Institutional Independence in the International Legal Order. Abingdon & New York: Routledge.

Cooper, S., Hawkins, D. G. & Jacoby, W. & Nielson, D. (2008) Yielding Sovereignty to International Institutions: Bringing System Structure Back. In: International Studies Review, 10, pp. 501–524.

Cornell, T., Gordon, R. & Smyth, M. (2019) Sanctions Law. Oxford: Hard Publishing.

Costa, O. (2008) Is Climate Change Changing the EU? The Second Image Reversed in Climate Politics. In: Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 21(4), pp. 527-544.

Costa, O. & Jørgensen K.E. (2012) The Influence of International Institutions on the EU: A Framework for Analysis. In: Costa, O. & Jørgensen K.E. eds. The Influence of International Institutions on the EU. When Multilateralism hits Brussels. Basingstoke & New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Council of the European Union (2002) Council Framework Decision of 13 June 2002 on Combating Terrorism. 2002/475/JHA. Available at: >https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32002F0475&from=EN< [Accessed: 17.01.2020].

Council of the European Union (2018) Guidelines on Implementation and Evaluation of Restrictive Measures (Sanctions) in the Framework of the EU Common Foreign and Security Policy. Available at: >https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-5664-2018-INIT/en/pdf< [Accessed: 17.01.2020].

Council of the European Union (2008) Revised Strategy on Terrorist Financing. Available at: >http://register.consilium.europa.eu/doc/srv?l=EN&f=ST%2011778%202008%20REV%201< [Accessed: 22.01.2020].

Cox, R. W. (1986) Social Forces, States and World Orders: Beyond International Relations Theory, in: Keohane, R. O. (ed.): Neorealism and its Critics, Columbia University Press: New York, 204-254.

Cremona, M. (2008) The European Union as an International Actor: The Issues of Flexibility and Linkage. In: Rees, W. & Smith, M. eds. International Relations of the European Union. Volume III. Los Angeles, London, New Delhi & Singapore: SAGE Publications. pp. 333-350.

Dai, X. & Martinez, G. (2012) How Do International Institutions Influence the EU? Advances and Challenges. In: Costa, O. & Jørgensen K.E. eds. The Influence of International Institutions on the EU. When Multilateralism hits Brussels. Basingstoke & New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 207-227.

De Búrca, G. (2010) The European Court of Justice and the International Legal Oder after Kadi. In: Harvard International Law Journal, 51(1), pp. 1-49.

Della Giovanna, M. & Kaunert, C. (2010) Post-9/11 EU Counter-terrorist Financing Cooperation: Differentiating Supranational Policy Entrepreneurship by the Commission and the Council Secretariat. In: European Security, 19(2), pp. 275-295.

Dekker, I.F. & Wessel R.A. (2004) ‘Governance by International Organisations: Rethinking the Source and Normative Force of International Decisions’, in I.F. Dekker and W. Werner (Eds.), Governance and International Legal Theory. Leiden & Boston: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, pp. 215-236.

Drieskens, E. & Van Schaik L. (Eds.) (2014) The EU and Effective Multilateralism: Internal and External Reform Practices. London & New York: Routledge.

Drüner, D., Klüver, H., Mastenbroek, E. et al. (2018) The Core or the Winset? Explaining Decision-Making Duration and Policy Change in the European Union. In: Comparative European Politics, 16, pp. 271–289.

Duffield, M. (2007) What are International Institutions? In: International Studies Review, 9(1), pp. 1-22.

Eling, K. (2007) The EU, Terrorism and Effective Multilateralism. In Spence, D. (Ed.) The European Union and Terrorism. London: John Harper.

Elliott, K. A. (2010) Assessing UN Sanctions after the Cold War: New and Evolving Standards of Measurement. In: International Journal, 65(1), pp. 85-97.

European Commission (n.d.) EU Sanctions Map. Available at: >https://www.sanctionsmap.eu/#/main< [Accessed: 25.01.2020].

European Commission (2015) The European Agenda on Security. Available at: >https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:52015DC0185< [Accessed: 22.01.2020].

European Council (2001a) Council Common Position of 27 December 2001 on Combating Terrorism. Available at: >https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32001E0930< [Accessed: 22.01.2020].

European Council (2001b) Conclusions and Plan of Action of the Extraordinary European Council Meeting on 21 September 2001. Available at: >https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/20972/140en.pdf< [Accessed: 18.01.2020].

European Council & Council of the European Union (2019) Adoption and Review Procedure for EU Sanctions. Available at: >https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/sanctions/adoption-review-procedure/< [Accessed: 18.01.2020].

European Council (2001c) Anti-Terrorism Roadmap. Available at: >https://www.statewatch.org/news/2001/oct/sn4019.pdf< [Accessed: 18.01.2020].

European Council & Council of the European Union (2019) EU at the UN General Assembly. Available at: >https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/unga/< [Accessed: 20.12.2019].

European Court of Justice (2008) Joined Cases C-402/05 P and C-415/05 P Yassin Abdullah Kadi and Al Barakaat International Foundation v Council of the European Union and Commission of the European Communities. Available at: >https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A62005CJ0402< [Accessed: 20.01.2020].

European Parliament (2019) The Fight Against Terrorism. Available at: >https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2019/635561/EPRS_BRI(2019)635561_EN.pdf< [Accessed: 21.01.2020].

European Union (2003) A Secure Europe in a Better World: European Security Strategy. Available at: >http://www.internationaldemocracywatch.org/attachments/307_European%20Security%20Strategy.pdf< [Accessed: 18.01.2020].

European Union (2012) Consolidated version of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. Available at: >https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:12012E/TXT&from=EN< [Accessed: 18.01.2020].

European Union (2005) Directive 2005/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 October 2005 on the Prevention of the Use of the Financial System for the Purpose of Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing. Available at: >https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32005L0060< [Accessed: 12.01.2020].

European Union (2017) Directive (EU) 2017/541 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 March 2017 on Combating Terrorism and Replacing Council Framework Decision 2002/475/JHA and Amending Council Decision 2005/671/JHA. Available at: >https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32017L0541< [Accessed: 22.01.2020].

European Union (2015) Directive 2015/849 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 May 2015 on the Prevention of the Use of the Financial System for the Purposes of Money Laundering or Terrorist Financing, Amending Regulation (EU) No 648/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council, and Repealing Directive 2005/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council and Commission Directive 2006/70/EC. Available at: >https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:02015L0849-20180709< [Accessed: 22.01.2020].

European Union (2002) EU Rules on Terrorist Offences and Related Penalties. Available at: >https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=LEGISSUM%3Al33168< [Accessed: 20.01.2020].

European Union (2018) Regulation (EU) 2018/1672 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2018 on Controls on Cash Entering or Leaving the Union and Repealing Regulation (EC) No 1889/2005. Available at: >https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/ALL/?uri=CELEX:32018R1672< [Accessed: 22.01.2020].

European Union (2007) Treaty of Lisbon amending the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty establishing the European Community, signed at Lisbon, 13 December 2007. 2007/C 306/01. Available at: >https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:12007L/TXT< [Accessed: 23.12.2019].

Ferreira-Pereira, L. C. & Martins, B. O. (2012) The External Dimension of the European Union’s Counter-Terrorism: An Introduction to Empirical and Theoretical Developments. European Security, 21(4), pp. 459-473.

Flick, Uwe (2009). An Introduction to Qualitative Research. 4th Ed. London: SAGE Publications.

Gardner, K. L. (2007) Terrorism Defanged: The Financial Action Task Force and International Efforst to Capture Terrorist Finances. In: Cortrights D. & Lopez, G.A. (Eds) Uniting Against Terror: Cooperative Nonmilitary Responses to the Global Terrorist Threat. Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press.

Gehring, T. & Oberthür S. (2006) Introduction. In: Gehring, T. & Oberthür S. (Eds.) Institutional Interaction in Global Environmental Governance: Synergy and Conflict among International and EU Politics. Cambridge & London: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, pp. 1-19.

Gehring, T. & Oberthür S. (2009) The Causal Mechanisms of Interaction between International Institutions. In: European Journal of International Relations, 15(1), pp. 125-156.

Gerring, J. (2007) Case Study Research. Principles and Practices. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gourevitch, P. (1978) The Second Image Reversed: The International Sources of Domestic Politics. In: International Organization, 32(4), pp. 881-912.

Gregory, F. (2005) The EU’s Response to 9/11: A Case Study of Institutional Roles and Policy Processes with Special Reference to Issues of Accountability and Human Rights. In:Terrorism and Political Violence, 17(1-2), pp. 105-123.

Gutierrez-Fons, J. A. & Tridimas, T. (2008) EU Law, International Law, and Economic Sanctions against Terrorism: The Judiciary in Distress. In: Fordham International Journal, 32(2), pp. 660-730.

Hall, Peter A. (2008) Systematic Process Analysis: when and how to use it. In: European Political Science, 7, pp. 304-317.

Hall, P. A. & Taylor, R. C. R. (1996) Political Science and the Three Institutionalism. In: Political Studies, 44(5), pp. 936-957.

Haverland, M. (2007) Methodology. In: Graziano, P. & Vink, M. P. (Eds.). Europeanization: New Research Agendas. New York: Palgrave, pp. 59- 70.

Heng, Y. K. & McDonagh, K. (2008) The Other War on Terror Revealed: Global Governmentality and the Financial Action Task Force’s Campaign against Terrorist Financing. Review of International Studies, 34(3), pp. 553-573.

Héritier, A. (2001) Differential Europe: National Administrative Responses to Community Policy. In: Caporaso, J., Cowles, M.G. & Risse, T. (Eds.) Transforming Europe: Europeanization and Domestic Change. Ithaca & London: Cornell University Press, pp. 44-59.

Hill, C., Smith, M. & Vanhoonacker, S. (2017) International Relations and the European Union. 3. Ausgabe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 3-20.

Hix, S. (1998) The Study of the European Union II: The ‘New Governance’ Agenda and its Rival. In: Journal of European Public Policy, 5(1), pp. 38-65.

Hoffmeister, F. (2007) ‘Outsider of Frontrunner? Recent Developments under International and European Law on the Status of the European Union in International Organizations and Treaty Bodies’, In: Common Market Law Review, 2007, pp. 41-68.

Hurd, I. (2002) Legitimacy, Power, and the Symbolic Life of the UN Security Council. In: Global Governance, 8(1), pp. 35-51.

Johnston, A. I. (2001) Treating International Institutions as Social Environments. In: International Studies Quarterly, 45, pp. 487-515.

Jørgensen, K. E. (2009) The European Union and International Organizations. London: Routledge, p. 188.

Jørgensen K.E. & Laatikainen K.V. (2013) (Eds.), Routledge Handbook on the European Union and International Institutions: Performance, Policy, Power. London: Routledge.

Jørgensen, K.E. & Wessel, R.A. (2011) The Position of the European Union in (other) International Organizations: Confronting Legal and Political Approaches. In: P. Koutrakos (Ed.), European Foreign Policy: Legal and Political Perspectives, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 261-286.

Karns, M. P. & Mingst, K. A. (1992) (Eds.) The United States and Multilateral Institutions: Patterns of Changing Instrumentality and Influence. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

Kasa, S, (2013) The Second-Image Reversed and Climate Policy: How International Influences Helped Changing Brazil’s Positions on Climate Change. In: Sustainability, 5(3), pp. 1051-1053.

Kaunert, C. & Léonard, S. (2012) Combating the Financing of terrorism Together? The Influence of the United Nations on the European Union´s Financial Sanction System. In: Costa, O. & Jørgensen K.E. eds. The Influence of International Institutions on the EU. When Multilateralism hits Brussels. Basingstoke & New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kelley, J. (2004) International Actors in the Domestic Scene: Membership Conditionality and Socialization of International Institutions. In: International Organization, 58(3), pp. 425-457.

Keohane, R. O. (1998) International Institutions: Can Independence Work? In: Foreign Policy, No. 110, Special Edition: Frontiers of Knowledge, pp. 82- 96.

Keohane, R. O. (1988) International Institutions: Two Approaches. In: International Studies Quartely, 32(4), pp. 379-396.

King, D. S., Peters, G. & Pierre, J. (2005) The Politics of Path Dependency: Political Conflict in Historical Institutionalism. In: The Journal of Politics, Vol. 67(4), pp. 1275-1300.

Koremenos, B., Lipson, C. & Snidal, D. (2001) The Rational Design of International Institutions. In: International Organization, 55(4), pp. 761-799.

Manners, I. (2002) Normative Power Europe: A Contradiction in Terms? In: Journal of Common Market Studies, 40 (2), pp. 235-258.

Manners, I. & Whitman, R. (2003) The “Difference Engine”: Constructing and Representing the International Identity of the European Union. In: Journal of European Public Policy, 10(3), pp. 380-404.

Martin. L. L. & Simmons, B. A. (2005) International Organizations and Institutions. In: Carlsnaes, W., Risse, T. & Simmons, B. A. (Eds.) Handbook of International Relations. 3rd ed. London, New Delhi & Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, pp. 192- 212.

Martin. L. L. & Simmons, B. A. (1998) Theories and Empirical Studies of International Institutions. In: International Organization, pp. 719-57.

Mathiason, J. R. (2007) Invisible Governance: International Secretariats in Global Politics. Bloomfield: Kumarian Press.

Mitchell, R. B. (2009) The Influence of International Institutions: Institutional Design, Compliance, Effectiveness, and Endogeneity. In: Milner H. V. & Moravcsik, A. (Eds.) Power, Interdependence, and Nonstate Actors in World Politics, Princeton & Oxford: Princeton University Press, pp. 64-88.

North, D. (1991) Institutions. In: Journal of Economic Perspectives. 5(1), pp. 97-112.

Odermatt, J., Ramopoulos, T. & Wouters, J. (2014) ‘The Status of the European Union at the United Nations General Assembly’, in I. Govaere et al. (Eds.), The European Union in the World: Essays in Honour of Marc Maresceau, Leiden/Boston: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, pp. 211-223.

Olson, M. (1971) The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 53-60.

Pavoni, P. (1999) UN Sanctions in EU and National Law: The Centro-Com Case, In: International and Comparative Law Quarterly, 48(3), pp. 582-612

Peers, S. (2003) EU Responses to Terrorism. In: International Comparative Law Quarterly, 52, pp. 227-243.

Radealli, C. M. (2003) The Europeanization of Public Policy. In: Featherstone, K. & Radaelli, C. M. (Eds.) The Politics of Europeanization, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Richard, A. C. (2005) Fighting Terrorist Financing: Transatlantic Cooperation and the International Institutions. Washington D.C.: John Hopkins University – Center for Transatlantic Relations.

Risse, T. (2002) Transnational Actors in World Politics. In: Carlsnaes, W., Risse, T. & Simmons, B. A. (Eds.) Handbook of International Relations. 2nd ed. London, New Delhi & Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, pp. 255-274.

Russel, M. (2018) EU Sanctions: A Key Foreign and Security Policy Instrument. Available at: >https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2018/621870/EPRS_BRI(2018)621870_EN.pdf< [Accessed: 02.01.2020].

Scheffler, J. (2011) Die Europäische Union als rechtlich-institutioneller Akteur bei den Vereinten Nationen. In: Von Bogandy, A. & Wolfrum R. eds. Beiträge zum ausländischen öffentlichen Recht und Völkerrecht. Band 220. Dordrecht, Heidelberg, London & New York: Springer, pp. 1-51.

Stephen, M. & Zürn. M. (2010) The View of Old and New Powers on the Legitimacy of International Institutions. In: POLITICS, 30(1), pp. 91-101.

Stetter, S. (2004) Cross-pillar Politics: Functional Unity and Institutional Fragmentation of EU Foreign Policies. In: Journal of European Public Policy, 11(4), pp. 720-739.

Spence, D. (2007) The European Union and Terrorism. London: John Harper.

Tseblis, G. (2000) Veto Players and Institutional Analysis. In: Governance; An International Journal of Policy and Administration, 14(4), pp. 441-474.

United Nations (1945) Charter of the United Nations and the Statute of the International Court of Justice. Available at: >https://treaties.un.org/doc/publication/ctc/uncharter.pdf< [Accessed: 15.01.2020].

United Nations (n.d.) Member States. Available at: >https://www.un.org/en/member-states/index.html< [Accessed: 23.12.2019].

United Nations (2011) Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 3 May 2011. Participation of the European Union in the work of the United Nations. A/RES/65/276. Available at: >https://undocs.org/A/RES/65/276< [Accessed: 23.12.2019].

United Nations General Assembly (2019) Contributions received for 2019 for the United Nations Regular Budget. Available at: >https://www.un.org/en/ga/contributions/honourroll.shtml< [Accessed: 23.12.2019].