Back in 2003, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTD) hailed the emergence of a world market for corporate headquarters (CHQs).[1] Multinational companies (MNCs) were becoming more internationally mobile. They were relocating their core business functions, and sometimes the global HQ itself, outside of their home countries to whichever country offered the most competitive perks. This trend continues to persist. In 2016, a KPMG report found that 76% of the 1,300 CEOs surveyed around the world were looking to relocate their CHQs.[2] Even iconic American companies have decided to move, including Burger King (to Canada), Budweiser (to Belgium), and Lucky Strike (to the UK).

However, American Big Tech bucks the trend. Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Microsoft are the world’s most valuable MNCs by market capitalization.[3] Their services mediate almost every facet of our lives, almost wherever we are: the tools we use to work, study, and play; how we shop and interact; the way companies operate and market their products. Accordingly, they have established offices and facilities across the world. Nonetheless, their CHQs have always remained in the United States (US).

Therefore, this paper asks: why does Big Tech stay headquartered in the US? For clarity, I adopt Markus Menz’s definition of CHQ as “the multimarket firm’s central organizational unit, which is structurally separate from the product and geographic operating units, and hosts corporate executives as well as central staff functions that fulfil various international and external roles”.[4] I find that existing explanations – such as emotional attachments, small tax obligations, friendly domestic regulations, and location bounded human resources – cannot fully elucidate why Big Tech stays headquartered at home. An alternative reason is necessary.

I argue that Big Tech remains headquartered at home to facilitate its aim of centring its corporate power in the US. Crucially, this enables Big Tech to influence the American government into advancing its interests domestically and internationally. Domestically, Big Tech shapes government regulations to augment its dominance in the American market – its most valuable market. Internationally, Big Tech relies upon America’s outsized influence to shape international trade agreements and extend its market dominance worldwide.

I begin by reviewing current explanations to elucidate the theoretical gap on the topic. Next, I introduce the theoretical logic of my argument. I then elaborate on how staying headquartered in the US enables Big Tech to amass corporate power there, and why Big Tech would want to amass its corporate power in the US. Finally, I conclude by briefly discussing whether Big Tech’s CHQs would stay in the US, given domestic pressure for regulatory reforms recently.

Literature review

To motivate the paper’s contribution, I demonstrate that current literature cannot fully explain why Big Tech firms continue locating their CHQs in the US, even as they have grown into global goliaths.

One popular explanation is that Big Tech founders, major shareholders, and top executives harbour a strong emotional attachment to America, and hence prefer their firms to stay headquartered there.[5] After all, almost all of them are Americans whose families and careers are rooted in America.

While this explanation seems plausible at first glance, there is little evidence that their emotional attachments do influence their business decisions to remain headquartered in the US. This is why we still see iconic US brands that were founded in America and led by Americans – i.e. Burger King and Seagate Technologies – choosing to relocate their CHQs overseas.

Another explanation is that Big Tech companies can minimize their tax obligations by remaining headquartered in the US. Big Tech firms have become adept at exploiting the corporate tax loopholes in the US to minimize their liabilities.[6] Between 2018 and 2020, their effective tax rate was only 15.4%, which is substantially below the global average of 25.85%.[7]

However, tax rates do not seem to be a key consideration for Big Tech when choosing to remain headquartered in the US. Otherwise, Big Tech would have shifted their CHQs to a tax haven, such as the Cayman Islands, where there is no corporate tax.[8] Moreover, Big Tech has become savvy at avoiding taxes wherever they operate, such that there is no need to pick a CHQ location based on lower tax rates.

A third explanation is that the human capital of Big Tech firms is location bounded in the US, making it difficult for them to relocate their CHQs overseas. Indeed, the English-speaking specialists leading the business operations of Big Tech are mostly Americans who are based in the US.[9] Despite the global mobility of small cadres of ambitious professionals, most specialists would be unwilling to migrate overseas for work.[10] Big Tech firms would need to gradually replace these specialists if they were to relocate their CHQs overseas. This creates strong lock-in effects among them.

This theory has explanatory power, but cannot fully capture why Big Tech remains headquartered at home. While recruiting and retraining new specialists would be costly for Big Tech firms, it is not an insurmountable task considering that they already have well-established regional headquarters overseas. Crucially, other considerations might take precedence over human capital.[11] For instance, iconic British MNCs – such as HSBC – relocated their headquarters overseas after Brexit.[12] This brings us to our last point.

The final explanation is that American domestic regulations are friendly to Big Tech, making the US the most ideal place to base its core activities and CHQs. Big Tech firms are most concerned with three areas of regulation: antitrust, intellectual property (IP), and privacy. Crucially, they benefit from America’s weak regulations across all three areas. Antitrust laws have not constrained Big Tech firms, despite their market dominance over a broad range of digital services.[13] The weakening of IP laws impedes smaller firms with disruptive technologies from entering the market and limits their threat to the dominance of Big Tech.[14] Weak privacy laws permit Big Tech to collect and translate user data into behavioural data for sale with little transparency or safeguards.[15] Significantly, this enables Big Tech to enhance its dominance over the American market, which is of utmost importance because it generates the most revenue for Big Tech.[16]

This explanation is compelling but incomplete. For starters, Big Tech is not only concerned with the present state of regulations, but also their ability to influence these regulations to guarantee their long-term interests. Furthermore, Big Tech’s agenda goes beyond maintaining friendly domestic regulations, to creating an international regulatory environment that protects their interests. These two themes are not captured in the explanation.

Therefore, there appears to be a theoretical gap in explaining why Big Tech remains headquartered in the US. The next section outlines a new theory to address the gap.

Theoretical framework

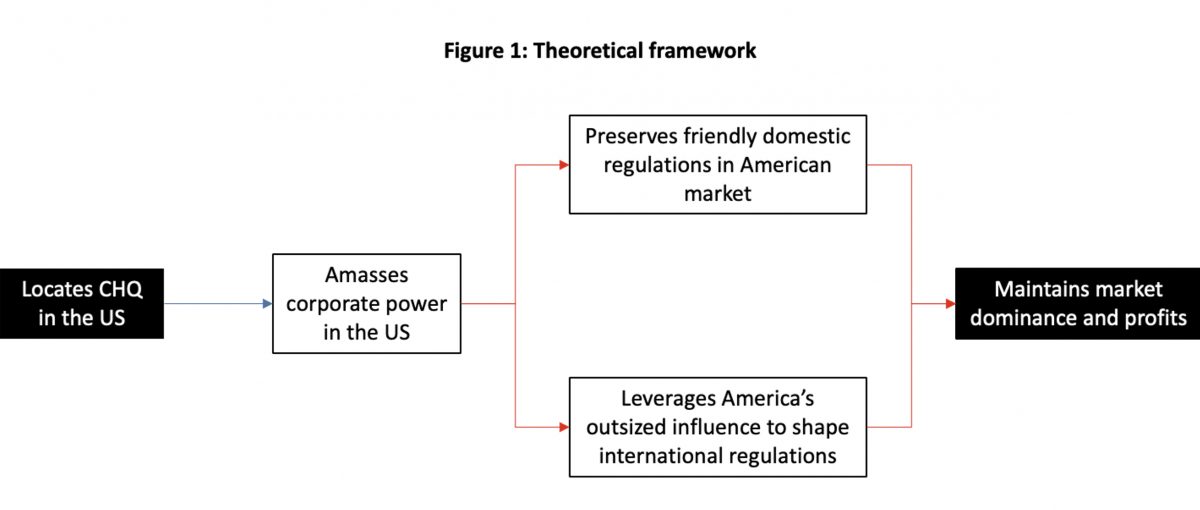

I argue that staying headquartered in the US facilitates Big Tech’s strategic endeavour to amass its corporate power there. This theory can be broken down into two propositions, as depicted in Figure 1. First, Big Tech’s decision to remain headquartered in the US facilitates its endeavour to amass its corporate power there. Second, Big Tech benefits most from amassing its corporate power in the US than anywhere else in the world.

I define “corporate power” as the political power possessed by a corporation – that is, its capacity to influence the actions, beliefs, or behaviours of others. The “three faces of power” framework created by Doris Fuchs and Markus Lederer, and developed upon by John Mikler, is useful for unpacking the complexity of corporate power. According to them, corporate power is a function of a company’s instrumental, structural, and discursive power.[17]

Instrumental power refers to Big Tech’s capacity to directly influence the actions, policies, or decisions of government officials to favour its interests.[18] Big Tech primarily develops its instrumental power by lobbying officials at all three levels of government (national, state, and local) and all three branches of government (legislature, executive, and judiciary). It typically entails personal meetings with government officials, and regular participation in the official hearings and special committee sessions organised by public agencies.[19]

In contrast, structural power refers to Big Tech’s capacity to create or reinforce institutional practices that limit the scope of public consideration to those issues which are harmless to them.[20] Big Tech amasses structural power as it gains market dominance over a wide range of digital services. It now forms the infrastructural core of an ever-expanding tech universe, operating as obligatory digital interfaces for all forms of social exchange – how we work, study, and play; how we shop and interact; how companies operate and market their products.

Thirdly, discursive power refers to Big Tech’s capacity to influence politics and political processes through the shaping of norms and ideas.[21] Big Tech accumulates discursive power through its propaganda campaign. It uses advertisements to change public perceptions of tech regulations. For instance, Facebook sponsored articles and advertisements advocating for “updated internet regulations” on socio-political websites, whose readership includes government officials and public interest groups.[22] Big Tech also funds think tanks and academics who may research, advocate, and publish in its favour, without necessarily disclosing their benefactors.[23] Importantly too, the public appearances of Big Tech executives are carefully scripted to propagate a friendly brand image.[24]

However, the “three faces of power” framework currently overlooks an important characteristic of corporate power: Corporate power – and its constituent powers – is inherently location bounded. Big Tech could foster its corporate power in the US, but this will likely not translate into more corporate power in the EU or any other country. Significantly, this creates a problem of scarcity for Big Tech. Big Tech requires tremendous resources to foster its corporate power in any one country, but has limited resources. It must, therefore, spread its resources according to the strategic importance of each country. The more important a country is to Big Tech’s profits, the more resources it will put into fostering corporate power there.

Consider now that CHQs are where companies’ key resources are centralized. As such, the location of a corporate’s headquarters maximises its ability to accumulate corporate power in that particular country. This is my theory’s first proposition. I will elaborate upon this proposition in the next section, as I detail how staying headquartered in the US facilitates Big Tech’s accumulation of corporate power there.

But this begs the question: Why would Big Tech want to amass its corporate power in the US? This brings us to my theory’s second proposition. My theory suggests two reasons why Big Tech wants to amass its corporate power in the US. First, it enables Big Tech to preserve friendly domestic regulations in the American market from which it derives the most revenue. Second, it allows Big Tech to leverage America’s outsized influence in international politics to shape international digital agreements and facilitate its global expansion. These reasons will be elaborated upon in the later section of the paper.

Staying headquartered in the US

This section presents three key pieces of evidence to demonstrate that Big Tech’s decision to remain headquartered in the US is driven by its endeavour to centralize its power in the US.

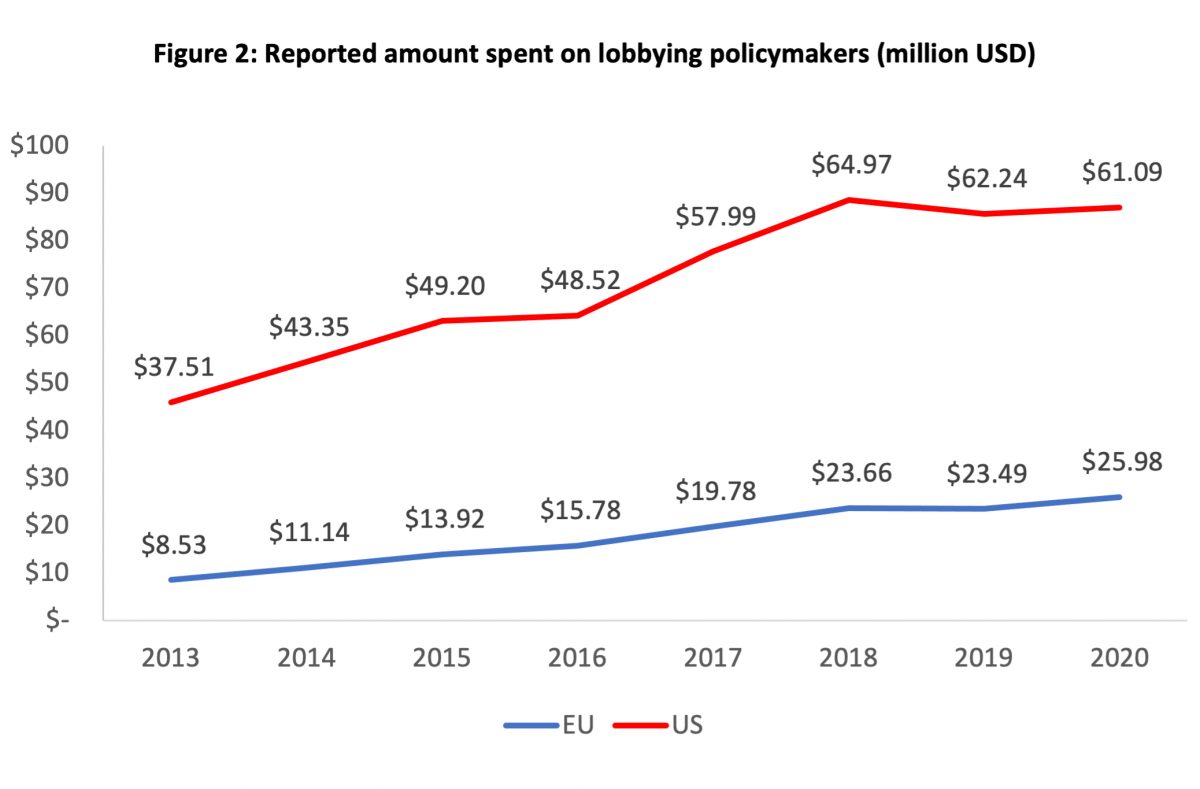

Firstly, staying headquartered in the US facilitates Big Tech’s lobbying efforts, which are mainly targeted at American government officials. In Figure 2, I compare the total amount that Big Tech spent on lobbying policymakers in the US and European Union (EU) from 2013 to 2020.[25] I chose the US and EU because these are where Big Tech spends the most on lobbying. We observe that Big Tech spends at least 2.5 times more lobbying in the US than EU annually throughout the 8 years. This suggests that Big Tech prioritizes fostering its instrumental power in the US than anywhere else. Crucially, locating its CHQ in the US enables Big Tech firms to better coordinate their lobbying efforts there. Their CHQ each houses a Global Government Affairs and Public Policy team. Staying in the US enables the team to manage a larger pool of lobbyists locally to sustain more extensive lobbying efforts at the grassroots, state, and federal levels.[26] As we shall examine later, this is critical to maintaining friendly domestic regulations and entrenching their dominance in the American market, from which they derive the most revenue. The proximity is also important to maintaining a close collaboration with American government officials on shaping international digital agreements.

Secondly, staying headquartered in the US enhances Big Tech’s “Americanness” among American citizens and government officials. Big Tech firms have been strategically portraying themselves as Americans as opposed to any other nationalities. They claim to represent American values of “democracy, competition, inclusion, and free expression” on the world stage, against the menacing rise of Chinese tech which is “highly censored, state-controlled, and a platform for surveillance”.[27] They also claim to be supporting the American economy and its workforce (more than anywhere else) through their investments in domestic suppliers and manufacturers.[28] Remaining headquartered in the US reinforces its publicized commitment towards being American and contributing to American society, thereby boosting public perception of its “Americanness”. Significantly, this imbues Big Tech with the discursive power to claim that its business practices are aligned with America’s public interests, and hence legitimatize its dominance among the American public and government officials.

Thirdly, Big Tech remains headquartered in the US to strengthen its business ties with the American government and cultivate a structural dependency on it. Big Tech’s proximity to politicians and bureaucrats across all levels of government enables it to access more opportunities for closed tenders, gain insights on tender requirements behind closed doors, and galvanise support for its bid. Moreover, staying headquartered in the US strengths its “Americanness”, which enables it to access government tenders that involve critical public services, such as military defence, internal security, and public healthcare. As such, between 2010 and 2018, Big Tech firms have collectively secured more than 5,000 contracts with federal agencies.[29] They have been instrumental to the modernization of the US military under the Department of Defence (DoD).[30] Furthermore, their technologies assist the Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) arrests, detentions, and deportations of immigrants.[31] Importantly too, Big Tech firms have been the primary source of user data for the National Security Agency’s (NSA) domestic and international surveillance programmes.[32]

Significantly, this augments Big Tech’s structural power over the American government. Big Tech asserts that its “market size” allows it to sustain its investments into developing the network infrastructure that public agencies and ordinary Americans rely upon.[33] Stringent regulations to weaken their market size would only impede innovations and harm American interests. Therefore, even as the American government recognises the threat of Big Tech’s dominance to consumers and democracy, it remains wary of regulating them.

Centring corporate power in the US

Thus far, I have demonstrated that Big Tech stays headquartered in the US to facilitate its aim of centring its corporate power there. This section will elaborate on why Big Tech wants to amass its corporate power in the US in the first place.

Preserving friendly domestic regulations in the American market

One reason is that Big Tech firms prioritize maintaining their dominance in the American market, because it is the most valuable market to them. The American market is Big Tech’s biggest source of revenue.[34] American consumers have the most disposable income to purchase Big Tech’s products and services. American businesses invest heavily in e-commerce, advertising, and other digital services offered by Big Tech to reach local and international consumers from the US. The American government also offers large public projects to Big Tech. As a result, Big Tech is most anxious about maintaining its dominance in the American market, which compels them to stay headquartered in the US. I will draw upon the example of US privacy laws to illustrate my case.

Staying headquartered in the US has facilitated Big Tech’s lobbying efforts to maintain lax privacy laws locally. The US supports self-regulation and lacks a comprehensive framework on personal data such as the one provided by the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). As a result, American consumers’ privacy rights are poorly protected, allowing Big Tech companies to exploit their personal data for commercial use.[35]

Leveraging its proximity to US policymakers at the federal and state level, Big Tech has been actively lobbying them to resist public demand for more stringent privacy laws. At Capitol Hill, Big Tech has directly lobbied four committees in Congress with jurisdiction over privacy legislation: the House Judiciary Committee, the House Energy and Commerce Committee, the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, and the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation. 94% of the members of these have received a financial contribution from Big Tech in 2020. Democrats and Republicans alike benefitted from these funds, which totalled more than $3 million.[36] Consequently, Congress has failed to reform its privacy legislation or strengthen the enforcement of its existing privacy regulations.

Big Tech’s efforts also extend to state policymakers. It has been seeding water-down “privacy” legislation in states to pre-empt greater protection. Thus far, it has lobbied policymakers in more than 20 states, 14 of which has adopted state privacy bills endorsed by Big Tech but deemed too weak for consumers by privacy advocates.[37]

Overall, this example demonstrates how staying headquartered in the US strengthens Big Tech’s instrumental power in preserving friendly regulations in the American market, which is by far its most valuable consumer market.

Leveraging America’s outsized influence in international politics

The second reason why Big Tech centralises its corporate power in the US is to leverage America’s outsized influence in international digital trade to advance its agenda. As the UNCTAD notes, the international digital trade agenda “reflects the interests of the major digital owners and their superstar firms, which are reaping first-move advantages”.[38] Again, this motivates Big Tech to stay headquartered in the US. I illustrate this case through the recent international repeal of digital-service taxes.

Big Tech successfully collaborated with the US government to fend off proposals by European countries, UK, India, Indonesia, and Brazil to levy digital-service taxes on large tech companies. At the OECD and G20 meetings in July 2021, the US warned that it deemed such digital-service taxes as discriminatory against American tech companies. Instead, the US spearheaded an agreement to create a global minimum 15% corporate tax rate and scrape digital-service taxes.[39] While Big Tech companies will still have to pay more taxes overseas under the global tax agreement, the worldwide adoption of digital-service taxes would have cost them more.

Significantly, Big Tech’s proximity to US policymakers enabled them to shape their agenda at these talks. Through its network of connections within the federal government (forged through federal contracts, lobbying, and its public image), Big Tech persuaded US officials that the digital-service taxes threatened their competitiveness overseas and therefore indirectly harms the American economy. It maintained direct contact with US officials through regular meetings in Capitol Hill. Crucially, it offered suggestions on how the US can intervene to protect them, and helped to galvanise support among international policymakers on the behalf of US policymakers.[40]

This example reflects how Big Tech leveraged its structural and discursive power to persuade the US government into protecting its interests (and hence market dominance) internationally. These powers were, in part, enhanced by Big Tech’s proximity to the US policymakers.

Conclusion

Despite domestic pressure to regulate them in recent years, Big Tech will likely remain headquartered in the US. As discussed, Big Tech enjoys tremendous benefits from centring its corporate power in the US than anywhere else. One reason is that it enables Big Tech to preserve friendly domestic regulations in the American market, from which it derives the most revenue. Another reason is that it allows Big Tech to leverage America’s outsized influence to shape international digital agreements. In turn, this motivates Big Tech to stay headquartered in the US, because it facilitates their amassing of corporate power there. Overall, this paper is an attempt at developing a new theory to explain why Big Tech remains headquartered in the US, but more empirical testing is necessary. Specifically, a small-N comparative case study between Big Tech and other American companies that have relocated their CHQs might yield more insights.

Notes

[1] “World Market for Corporate HQs Emerging,” United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTD), accessed October 20, 2021, https://unctad.org/press-material/world-market-corporate-hqs-emerging.

[2] Carmen Raluca Stoian, “Why Big Businesses Move Their Headquarters Around the World,” The Conversation, accessed October 20, 2021, https://theconversation.com/why-big-businesses-move-their-headquarters-around-the-world-tax-talent-and-trepidation-110913.

[3] “Largest tech Companies by Market Cap,” Companies Market Cap, accessed October 20, 2021, https://companiesmarketcap.com/tech/largest-tech-companies-by-market-cap/.

[4] Markus Menz, Sven Kunisch and David J. Collis, “The Corporate Headquarters in the Contemporary Corporation: Advancing a Multimarket Firm Perspective,” Academy of Management Annals 9, no. 1 (Jan 2015): 633-714, https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2015.1027050.

[5] Klaus E. Meyer and Gabriel R.G. Benito, “Where Do MNEs Locate Their Headquarters? At Home!” Global Strategy Journal 6, No.2 (May 2016): 149-159, https://doi-org.libproxy1.nus.edu.sg/10.1002/gsj.1115.

[6] Tomoshizu Kawase, Maki Sagami and Tokio Murakami, “Big Tech Tax Burdens Are Just 60% of Global Average,” Nikkei Asia, accessed October 20, 2021, https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Datawatch/Big-Tech-tax-burdens-are-just-60-of-global-average.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Tax Justice Network, “Corporate Tax Haven Index – 2021 Results”, accessed October 20, 2021, https://cthi.taxjustice.net/en/cthi/cthi-2021-results.

[9] Kate Rooney and Yasmin Khorram, “Tech Companies Say They Value Diversity, But Reports Show Little Change in Last Six Years,” CNBC, accessed October 20, 2021, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/06/12/six-years-into-diversity-reports-big-tech-has-made-little-progress.html.

[10] Patrick Adler and Richard Florida, “Geography as Strategy: The Changing Geography Of Corporate Headquarters In Post-Industrial Capitalism,” Regional Studies 54, no.5 (August 2019): 610-620. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1634803.

[11] Patrick Adler and Richard Florida, “Geography as Strategy,” 615.

[12] Toby Helm, “UK Firms Plan to Shift Across Channel After Brexit Chaos,” The Guardian, accessed October 20, 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2021/jan/30/uk-firms-plan-to-shift-across-channel-after-brexit-chaos.

[13] Sheelah Kolhatkar, “What’s Next for the Campaign to Break Up Big Tech,” The New Yorker, accessed October 20, 2021, https://www.newyorker.com/business/currency/whats-next-for-the-campaign-to-break-up-big-tech

[14] Jonathan M. Barnett, “Why Big Tech Likes Weak IP,” CATO Institution, accessed October 20, 2021, https://www.cato.org/regulation/spring-2021/why-big-tech-likes-weak-ip.

[15] Asuncion Esteve, “The Business of Personal Data: Google, Facebook, and Privacy Issues in the EU and the USA,” International Data Privacy Law 7, no.1 (February 2017): 36-47.

[16] Omri Wallach, “How Big Tech Makes Their Billions,” Visual Capitalist, accessed October 20, 2021, https://www.visualcapitalist.com/how-big-tech-makes-their-billions-2020/.

[17] Mikler, The Political Power of Global Corporations (Cambridge: Polity, 2018), 33.

[18] Ibid, 35.

[19] Anthony J. Nownes, Total Lobbying: What Lobbyists Want (And How They Try to Get It) (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 12-36.

[20] Mikler, Global Corporations, 40.

[21] Ibid, 45.

[22] Jane Chung, “Big Tech, Big Cash: Washington’s New Power Players,” Public Citizen, accessed October 20, 2021, https://www.citizen.org/article/big-tech-lobbying-update/.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Malminderjit Singh, “Commentary: Big Tech is Showing Some Love To the US Government – Which Comes As No Surprise,” Channel News Asia, accessed October 20, 2021, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/commentary/tech-advocacy-lobbying-government-relations-policy-845761.

[25] OpenSecrets, Lobbying Data, (October 20, 2021), https://www.opensecrets.org; LobbyFacts, Lobbying Data, (October 20, 2021), https://lobbyfacts.eu.

[26] Nownes, Total Lobbying, 12-36.

[27] Anna Thompson, “Understanding Why Some Say China’s Internet Model Should Be Stopped,” Cincinnati Public Radio, accessed October 20, 2021, https://www.wvxu.org/local-news/2020-11-02/understanding-why-some-say-chinas-internet-model-should-be-stoppped.

[28] Apple, “Apple Accelerates US Investment and Job Creation,” Apple Newsroom, accessed October 20, 2021, https://www.apple.com/sg/newsroom/2018/01/apple-accelerates-us-investment-and-job-creation/.

[29] Jack Poulson, “Reports of a Silicon Valley/Military Divide Have Been Greatly Exaggerated,” Tech Inquiry, accessed October 20, 2021, https://techinquiry.org/SiliconValley-Military.

[30] Todd Harrison, “Battle Networks and the Future Force,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, accessed October 20, 2021, https://www.csis.org/analysis/battle-networks-and-future-force.

[31] Mijente, Immigrant Defense Project and the National Immigration Project of the National Lawyers Guild, “Who’s Behind ICE?”, Mijente, accessed October 20, 2021, https://mijente.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/WHO’S-BEHIND-ICE_-The-Tech-and-Data-Companies-Fueling-Deportations-_v1.pdf.

[32] Barton Gellman and Ashkan Soltani, “NSA Infiltrates Links to Yahoo, Google Data Centers Worldwide, Snowden Documents Say,” The Washington Post, accessed October 20, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/nsa-infiltrates-links-to-yahoo-google-data-centers-worldwide-snowden-documents-say/2013/10/30/e51d661e-4166-11e3-8b74-d89d714ca4dd_story.html.

[33] Foo Yun Chee, “Apple Denies Dominant Position Amid Antitrust Investigation,” Reuters, accessed October 20, 2021, https://www.reseller.co.nz/article/681002/apple-denies-dominant-position-amid-antitrust-investigation/.

[34] Omri Wallach, “How Big Tech Makes Their Billions,” Visual Capitalist, accessed October 20, 2021, https://www.visualcapitalist.com/how-big-tech-makes-their-billions-2020/.

[35] Esteve, “The Business of Personal Data,” 40.

[36] Chung, “Big Tech, Big Cash.”

[37] Todd Feathers, “Big Tech Is Pushing States to Pass Privacy Laws, and Yes, You Should Be Suspicious,” The Markup, accessed October 20, 2021, https://themarkup.org/privacy/2021/04/15/big-tech-is-pushing-states-to-pass-privacy-laws-and-yes-you-should-be-suspicious.

[38] United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), “What is At Stake for Developing Countries in Trade Negotiations on E-commerce,” UNCTAD, https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/ditctncd2020d5_en.pdf.

[39] Leigh Thomas, “130 Countries Back Global Minimum Corporate Tax of 15%,” World Economic Forum, accessed October 20, 2021, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/07/oecd-global-minimum-corporate-tax.

[40] Mark Scott and Emily Birnbaum, “How Washington and Big Tech won the Global Tax Fight,” Politico, accessed October 20, 2021, https://www.politico.eu/article/washington-big-tech-tax-talks-oecd/.

Bibliography

Adler, Patrick and Richard Florida. “Geography as Strategy: The Changing Geography of Corporate Headquarters In Post-Industrial Capitalism.” Regional Studies 54, no.5 (August 2019): 610-620. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1634803.

Apple. “Apple Accelerates US Investment and Job Creation.” Apple Newsroom. Accessed October 20, 2021. https://www.apple.com/sg/newsroom/2018/01/apple-accelerates-us-investment-and-job-creation/.

Barnett, Jonathan M. “Why Big Tech Likes Weak IP.” CATO Institution. Accessed October 20, 2021. https://www.cato.org/regulation/spring-2021/why-big-tech-likes-weak-ip.

Chung, Jane. “Big Tech, Big Cash: Washington’s New Power Players.” Public Citizen. Accessed October 20, 2021, https://www.citizen.org/article/big-tech-lobbying-update/.

Companies Market Cap. “Largest tech Companies by Market Cap.” Accessed October 20, 2021, https://companiesmarketcap.com/tech/largest-tech-companies-by-market-cap/.

Esteve, Asuncion. “The Business of Personal Data: Google, Facebook, and Privacy Issues in the EU and the USA.” International Data Privacy Law 7, no.1 (February 2017): 36-47.

Feathers, Todd. “Big Tech Is Pushing States to Pass Privacy Laws, and Yes, You Should Be Suspicious.” The Markup. Accessed October 20, 2021. https://themarkup.org/privacy/2021/04/15/big-tech-is-pushing-states-to-pass-privacy-laws-and-yes-you-should-be-suspicious.

Gellman, Barton and Ashkan Soltani, “NSA Infiltrates Links to Yahoo, Google Data Centers Worldwide, Snowden Documents Say.” The Washington Post. Accessed October 20, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/nsa-infiltrates-links-to-yahoo-google-data-centers-worldwide-snowden-documents-say/2013/10/30/e51d661e-4166-11e3-8b74-d89d714ca4dd_story.html.

Harrison, Todd. “Battle Networks and the Future Force.” Center for Strategic and International Studies. Accessed October 20, 2021. https://www.csis.org/analysis/battle-networks-and-future-force.

Helm, Toby. “UK Firms Plan to Shift Across Channel After Brexit Chaos.” The Guardian. Accessed October 20, 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2021/jan/30/uk-firms-plan-to-shift-across-channel-after-brexit-chaos.

Kawase, Tomoshizu, Maki Sagami and Tokio Murakami. “Big Tech Tax Burdens Are Just 60% of Global Average.” Nikkei Asia. Accessed October 20, 2021. https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Datawatch/Big-Tech-tax-burdens-are-just-60-of-global-average.

LobbyFacts. Lobbying Data. October 20, 2021. https://lobbyfacts.eu.

Menz, Markus, Sven Kunisch and David J. Collis. “The Corporate Headquarters in the Contemporary Corporation: Advancing a Multimarket Firm Perspective.” Academy of Management Annals 9, no. 1 (Jan 2015): 633-714. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2015.1027050.

Meyer, Klaus E. and Gabriel R.G. Benito. “Where Do MNEs Locate Their Headquarters? At Home!” Global Strategy Journal 6, No.2 (May 2016): 149-159. https://doi-org.libproxy1.nus.edu.sg/10.1002/gsj.1115.

Mijente, Immigrant Defense Project and the National Immigration Project of the National Lawyers Guild, “Who’s Behind ICE?” Mijente. Accessed October 20, 2021, https://mijente.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/WHO’S-BEHIND-ICE_-The-Tech-and-Data-Companies-Fueling-Deportations-_v1.pdf.

Nownes, Anthony J. Total Lobbying: What Lobbyists Want (And How They Try to Get It). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

OpenSecrets. Lobbying Data. October 20, 2021. https://www.opensecrets.org.

Poulson, Jack. “Reports of a Silicon Valley/Military Divide Have Been Greatly Exaggerated.” Tech Inquiry. Accessed October 20, 2021. https://techinquiry.org/SiliconValley-Military.

Rooney, Kate and Yasmin Khorram, “Tech Companies Say They Value Diversity, But Reports Show Little Change in Last Six Years.” CNBC. Accessed October 20, 2021. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/06/12/six-years-into-diversity-reports-big-tech-has-made-little-progress.html.

Scott, Mark and Emily Birnbaum. “How Washington and Big Tech won the Global Tax Fight,” Politico. Accessed October 20, 2021. https://www.politico.eu/article/washington-big-tech-tax-talks-oecd/.

Sheelah Kolhatkar. “What’s Next for the Campaign to Break Up Big Tech.” The New Yorker. Accessed October 20, 2021. https://www.newyorker.com/business/currency/whats-next-for-the-campaign-to-break-up-big-tech.

Singh, Malminderjit. “Commentary: Big Tech is Showing Some Love To the US Government – Which Comes As No Surprise.” Channel News Asia. Accessed October 20, 2021. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/commentary/tech-advocacy-lobbying-government-relations-policy-845761.

Stoian, Carmen Raluca. “Why Big Businesses Move Their Headquarters Around the World.” The Conversation. Accessed October 20, 2021. https://theconversation.com/why-big-businesses-move-their-headquarters-around-the-world-tax-talent-and-trepidation-110913.

Tax Justice Network, “Corporate Tax Haven Index – 2021 Results.” Accessed October 20, 2021. https://cthi.taxjustice.net/en/cthi/cthi-2021-results.

Thomas, Leigh. “130 Countries Back Global Minimum Corporate Tax of 15%.” World Economic Forum. Accessed October 20, 2021. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/07/oecd-global-minimum-corporate-tax.

Thompson, Anna. “Understanding Why Some Say China’s Internet Model Should Be Stopped.” Cincinnati Public Radio. Accessed October 20, 2021. https://www.wvxu.org/local-news/2020-11-02/understanding-why-some-say-chinas-internet-model-should-be-stoppped.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTD). “World Market for Corporate HQs Emerging.” Accessed October 20, 2021. https://unctad.org/press-material/world-market-corporate-hqs-emerging.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). “What is At Stake for Developing Countries in Trade Negotiations on E-commerce.” Accessed October 20, 2021. https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/ditctncd2020d5_en.pdf.

Wallach, Omri. “How Big Tech Makes Their Billions.” Visual Capitalist. Accessed October 20, 2021. https://www.visualcapitalist.com/how-big-tech-makes-their-billions-2020/.

Yun Chee, Foo. “Apple Denies Dominant Position Amid Antitrust Investigation.” Reuters. Accessed October 20, 2021. https://www.reseller.co.nz/article/681002/apple-denies-dominant-position-amid-antitrust-investigation/.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Gramscian Notions: Helpful for Research into Digital and Tech Corporations?

- 1.5 to Stay Alive: The Influence of AOSIS in International Climate Negotiations

- My Big Fat Greek Diaspora: Greek-American Diaspora Diplomacy

- Nuclear Proliferation and Humanitarian Security Regimes in the US & Norway

- The Anomaly of Democracy: Why Securitization Theory Fails to Explain January 6th

- Why Do Some Social Movements Succeed While Others Fail?