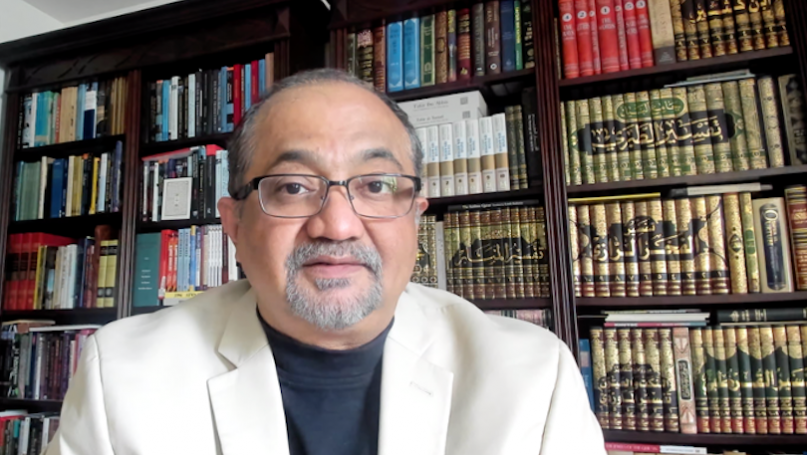

Dr. Muqtedar Khan is a Professor in the Department of Political Science and International Relations at the University of Delaware. He was the Academic Director of the State Department’s National Security Institute (2016-2019) and is the Academic Director of the American Foreign Policy Institute at the University of Delaware (2019-2022. He was a senior non-resident fellow of the Brookings Institution (2003-2008), a fellow of the Alwaleed Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding at Georgetown University (2006-2007), and a fellow of the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (2001-2016). He was a senior fellow with the Center for Global Policy (2016-2020) and is a Nonresident Scholar with the Newlines Institute. Dr. Khan earned his Ph.D. in International Relations, Political Philosophy, and Islamic Political Thought from Georgetown University in May 2000. He founded the Islamic Studies Program at the University of Delaware and was its first director from 2007-2010.

As an expert on governance, Islam and American foreign policy, he has lectured and trained scholars, students, elected leaders and policy makers in the U.S., Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Finland, Germany, UK, France, Turkey, Tunisia, Morocco, Egypt, India, Ireland, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, UAE, Qatar, Singapore, Canada, Argentina and Belgium. His most recent book is, – Islam and Good Governance: Political Philosophy of Ihsan, (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019). He is also the author of: American Muslims: Bridging Faith and Freedom (Amana, 2002), Jihad for Jerusalem: Identity and Strategy in International Relations (Praeger, 2004), Islamic Democratic Discourse (Lexington Books, 2006), and Debating Moderate Islam: The Geopolitics of Islam and the West (University of Utah Press, 2007). Dr. Khan is a frequent commentator in the international media. His articles and commentaries can be found at www.ijtihad.org. His research can be found here, tweets @Muqtedarkhan and he hosts a YouTube show called Khanversations.

Where do you see the most exciting research/debates happening in your field?

This is a difficult question to answer. I have never been confined to a single discipline. My current research is on India’s Grand Strategy and the vector of its political and economic development. I am particularly concerned about the emergence of a Hindu Rashtra and its impact on India’s democracy and the well-being of its minorities. The key questions in this area are about India’s strategic alignment and how its relationships with the US and China progress. My book before this current research was Islam and Good Governance. It explored the role of Sufism and Islam’s mystical values in advancing a vision of values based good governance that is democratic, inclusive, and attentive to national virtue as much as national interest. The debates in this area are about the role of Islam in the public sphere, the compatibility of Islam and democracy, and the modes of Islamic governance. Scholars and activists are both seeking to define an Islamic state that can address Muslim needs in contemporary times. Prior to that I was working on Islamic movements and US foreign policy in the Muslim World. This field continues to examine and explore the role of Islamists in Muslim politics and the emergence of violent extremism in the forms of Al Qaeda and Daesh. My first book was about American Muslims and their struggle to balance faith and freedom. I engaged in several debates that Muslims in the West are having about citizenship, democracy, gender equality and freedom. My dissertation, which was published under the title Jihad for Jerusalem, was about modifying constructivism to recognize that when core interests were not at stake, states would act rationally, but when their core values were at stake their choices would be shaped by their identity. The book seeks to bridge the divide between rationalism and reflectivism in international relations. I will continue to write about governance, values, Islamic enlightenment and reform even as I venture into new areas of research. I am driven by my own intellectual interests and not by disciplinary or paradigmatic debates.

How has the way you understood the world changed over time, and what (or who) prompted the most significant shifts in your thinking?

My understanding of social theory is influenced by Anthony Giddens’ theory of structuration, and it underpins my constructivist preferences. I have also learnt a lot from Michel Foucault’s work on power and how it influences the production of knowledge. Plato, Kant, Aristotle, Habermas, and Charles Taylor have also been influential. From among IR scholars, Nick Onuf and Andrew Bennett have both been very critical to my graduate studies. They both served on my dissertation committee, and I learned a lot from them about how to think about theory. My thought as well as my life is influenced by Islamic philosophers. Al Farabi, Ibn Khaldun, Ibn Rushd, Ibn Arabi, and Al Ghazali. Mevlana Rumi and Sheikh Saadi of Shiraz are also critical to my understanding of Islamic mysticism. My understanding of Ijtihad (an Islamic concept meaning independent thinking in jurisprudence) has been deeply influenced by Sheikh Taha Jaber al-Alwani. I have also learned a lot from John Esposito as his student and partner in several projects.

Some events too have had an impact on my thinking. The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 by Al Qaeda ended my career as an IR theorist and compelled me to turn towards the role of Islam in global politics exclusively for nearly two decades. My mission was to provide the most beautiful interpretation of Islam (as commanded by The Quran) that puts in relief the extremism of extremists. The way political Islamists have handled coming to power in Egypt after the Arab Spring ended my fond thinking that modern Islamists were a force for justice, democracy, and good governance. I was deeply disappointed by the decisions that they made when in power. I do not see them as the solution. The rise of Hindu nationalism in India and white supremacy in the US have convinced me that democratic institutions and structures of governance are not enough, we need something more to produce peaceful and vibrant societies. Perhaps we need to work on a philosophy of national virtue. State tuned.

How do you see the current reality of global geopolitics? What shifts do you envision in the great game?

We live in an age of geopolitical transition. The global order established by the U.S. in partnership with its allies after World War II is corroding. The institutions, the norms and the partnerships which enabled the US to sustain a liberal international order for nearly seven decades are all under serious stress from within and without. The rise of China, the rise of global authoritarianism and the decline of US relative power vis-à-vis China and the steady retreat of democracy are all putting stress on the system. The system has proven to be resilient and durable, but for how long? As the global order weakens, the geopolitical game becomes more intense because there is hope for systemic change, revisionist players like China, Russia, and Iran are emboldened and are willing to take more risks in the hope of greater rewards. The U.S. needs a new grand strategy, and we can see it is already reordering its priorities. Under the Biden administration the US has gone from promoting democracy abroad to rebuilding democracy at home. It has become an inward-looking state. It is retreating from the Middle East leaving room for both regional powers and Russia and China to increase their regional presence. While the US seeks to ensure that China does not dominate the Indo-Pacific region it remains to be seen if it can defend its own domination in Europe as Russia seeks to expand into Ukraine and Belarus. I expect the system to experience more unpredictability, more geopolitical contests, and the weakening of the current order.

While all eyes are focused on the rise of China, let us not forget that every region which the US seeks to withdraw from will allow room for China and Russia to expand and allow regional powers to rise. Going forward expect India, Iran, and Japan to become more geopolitically engaged and expect new alignments in Eurasia and the Middle East. Russia-Turkey, China-Iran, India-Japan, are partnerships that could become stronger and deeper. US’s enhanced engagement in the Indo-Pacific could weaken US-Europe ties and prompt France and Germany to think outside the NATO box.

What are the major challenges that the Muslim world faces at present? How can it begin to respond to these challenges?

The biggest challenge that the Muslim world faces is that it does not exist in institutional form. It is essentially a cultural phenomenon that is overlapped by the more powerful world of nation states. The support for China, tacit from some and vocal from other Muslim nations,on the issue of the Uyghurs and the general silence when it comes to Indian Muslims clearly signals that the biggest challenge for the Muslim World is that it does not exist in a form that can serve and advance its collective interests. The role of Islam in the public sphere remains unsettled. Muslims have a huge range of views on what role Islam should play in matters of governance and it creates tensions, often resulting in violence, when the real world of nation states collides with the aspirational world of a united, cohesive, moral, and powerful Muslim world that exists only in the imagination of Islamists. Security is a major issue for the Muslim World. Look at the major powers in the West, the US, UK, France, and Germany, they are not only in a robust security alliance but often act in concertin economic and cultural matters. Now look at the powers from the Muslim World, Turkey, Iran, Pakistan, Egypt, Saudi Arabia; they are oftenin discordwith each other rather than amity. Their major allies are outside the Muslim World. The Muslim World has no collective security arrangement or means of peaceful resolution of issues. The organization of Islamic countries (OIC) is ineffective.

There are endemic challenges that vary in intensity from state to state such as a democracy deficit, bad governance, high corruption, lag in scientific research, and lingering colonial maladies that are holding Muslims back. The only way Muslims can address these challenges is through reforms. They want the world to magically change and become subordinate to them. That will not happen. Muslims must first change themselves and only then can they negotiate a more favorably standing in the global order. The Muslim World needs to make good governance its first and foremost priority, over and above cultural and ideological pursuits.

Tell us more about your book Jihad for Jerusalem. What were you addressing in the book and what do you think are its contributions to the study of International Relations?

Jihad for Jerusalem: Identity and Choice in International Relations is based on my dissertation that tries to understand when states act rationally and when their actions are shaped by their identity, regardless of the material costs of those choices. Basically, asking what the exceptions are to rational choice-based explanations of state behavior. Or to phrase it in constructivist terms, when does identity matter? My answer is simple. All states have identities, some strong some weak and when core values are at stake, states with strong identities will chose policies that may not make rational sense but normatively and culturally are understandable. I also argue that Tigers, states with strong material capabilities and strong identities, will often act to reproduce their identities in the international arena. Whereas Mice, states with weak material power and incoherent identities, will generally act rationally. In the book I also examine the behavior of Paper Tigers, states with strong material capabilities but weak identities and Cubs, baby tigers with strong identities but weak material power. I try to advance a paradigm that bridges the gap between well-established claims of both rational and constructivist approaches to international relations.

Unfortunately, my career was hijacked by the realities of post-9/11 America and hence I was not able to pursue this line of research beyond my dissertation. I turned my attention to the geopolitics of Islam and the West and have never been able to return to my work on IR theory. It is only in recent months that I have been able to start working on Grand Strategy but the changing politics in India summons me. As a scholar of international relations and Islamic thought, I feel I cannot divorce myself from political realities of our times. I also see myself as a public intellectual and hence engagement with the community through the medium of ideas is my lifeblood. Nevertheless, despite my departure from IR theory, I feel that I have made a contribution by advancing a theory of agency in international relations that helps explain how states balance their material reality with their identity needs.

What is your vision for an Islamic democracy?

This debate about the compatibility of Islam and Democracy is a subset of the debate around the compatibility of Islam and modernity. I have tried to argue that those Muslims who reject modernity think of it as an ideology or a culture and reject it. But modernity is a long durée a la Fernand Braudel. It is a structure of history, and you must live through it.History, I submit, is inescapable. I critique those who insist that Islam is undemocratic by returning to the era of the Medinan State established and governed by Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) from roughly 622-632 AD. Sincethe debate hosted by the Boston Review under the titleIslam and the Challenge of Democracywhen I first brought up the importance of the constitution of Madinah, I have been advancing a political theory of Islamic democracy based on the constitution of Madinah as a social contract. In my book, Islamic Democratic Discourse, I took this discussion further along with profoundly thoughtful contributions from scholars like Tariq Ramadan, Asma Afsaruddin, Abdulaziz Sachadena and others. In my latest book, Islam and Good Governance: A Political Philosophy of Ihsan, I have not only described how an Islamic democratic state can be developed based on the three key characteristic of the Medinan state – constitution, consent and consultation – but also identified the conceptual shifts that Muslim societies need to make in order to realize it. I believe that an Islamic state based on Ihsan will emphasize good governance over ideology, self-governance over imposition of morality, provide both positive and negative liberties, and pay equal attention to national virtue along with national interest. Ihsan is the core concepts that anchors Islamic mysticism.

On examining your 2004 book Jihad for Jerusalem and the 2019 book Islam and Good Governance one can observe that your interests and thinking have clearly evolved over time?

Naturally. Thinking changes you and your thinking. Not only has my view of the world changed but my worldview too has evolved over time. So, in a way change has been both ontological and epistemological. I swim in two broad rivers. The first one is international relations understood broadly to include comparative politics, governance, and foreign policy. And the second one is Islamic thought also understood broadly to include Islamic philosophy, Islamic political thought, Islam and politics and Muslims in the West and now in India. The vectors of both rivers have changed. In the international relations field, I was a constructivist looking at things that constructivists look at, such as identity construction and its impact on interests. The paradigm was and is useful to study the role of Islam (as an identity) in international affairs. The Islamic in Islamic state, Islamic movements, Islamic politics is an identity marker and best apprehensible via constructivist lenses. But lately my interest in grand strategy has been dragging me towards looking at things that realists focus on, such as hard power, soft power, national capabilities, and relative balances of power. Butpossibly the constructivists principles in me are so deeply ingrained that even when I look at realist things my gaze is still constructivist.

In Islamic studies the change is easy to understand. In my early days I was firmly in the school of Islamic modernism like Allama Muhammad Iqbal, Professor Fazlur Rahman and Sir Syed Ahmed Khan. I was awarded the Sir Syed Ahmed Khan prize for lifetime service to Islamic thought in 2008. But when I started researching the concept of Ihsan– to do beautiful things – for my book Islam and Good Governance: A Political Philosophy of Ihsan, my life took a mystical turn. Mystical/Sufi readings of the Quran now influence the way I understand, interpret, teach, and practice Islam.

What is the most important advice that you would give to young scholars?

The audience of E-IR is global, so it is difficult to give advice to young scholars since the academic environment and institutional norms and forms vary so much across countries. But somethings are universal, and I can share those. First, research, write and teach about things that you are passionate about and I promise you, you will never work a single day in your life, and you will never ever want to retire. Your job will be your joy. Second, given the rapid growth of instructional technology do not romanticize notions such as “old school”. Use technology, be creative in research and while teaching. While expectations and remunerations may vary across nations, there is only one currency that counts and that is scholarship. Define it broadly if you like but remember it matters more than anything else and it will take you places. I established my website Ijtihad.org in 1997 and even though I do not update it as often now as before it is a daily source of joy because it tells me that thousands read my work every day. I have now started a YouTube channel called Khanversations. It has added a new dimension to my teaching and for me to impact the world with my thoughts, my research, and my views. I find these nontraditional avenues for disseminating my scholarship extremely rewarding. Try them. Remember, universities are the temples of modern civilization and scholars are the new priests. Approach your scholarship with dedication and sincerity, as if you are performing a sacred ritual.