More than a decade after the first sprouts of the Arab Spring started to blossom in December 2010, much has changed in the Arab world. Enduring the rise and fall of ISIS, witnessing insurgency and civil war in Iraq, Yemen, and Libya, experiencing a crisis, coup, and unrest in Egypt, as well as bearing the ongoing conflict in Syria has shaped and worn out societies from the Maghreb to the Mashriq as it has shaped many urban centres all over the region: a crumbling, devastated environment, often on the verge of deterioration. When Western media outlets review the events of the Arab Spring today, they often illustrate the political and societal changes during that time by recapitulating the personal fates of various leaders that lost their office during this episode (see Al-Jazeera, 2017; Holmes, 2020). But while Gaddafi’s death or Ben Ali’s ousting serve as apt examples for political groups, leaders, and movements that were swept away during the initial uprisings or throughout the following events, even after a decade of conflict and more than 600.000 deaths, reign over Syria remains firmly in the hands of Bashar Al-Assad.

By analysing Assad’s leadership style through a quantitative analysis of various personality traits, this paper endeavours to produce insights into the capabilities, behaviour, and character features that allow a leader to preserve power even under the most adverse conditions. After briefly reviewing the state and development of the existing literature and narratives in the field, we will elaborate on the methodology employed for this paper. Afterwards, a thorough analysis is conducted and the quantitative results are critically assessed, discussed, and compared to evaluations of Assad by other authors. Finally, we conclude that Assad, depending on the context, can be categorised as having either a reactive or accommodative leadership style — evaluating his possibilities in a given situation and considering what important actors will favour or allow, he focuses on building consensus in his environment, empowering others, sharing accountability, and reconciling differences between groups or people that he relies on.

Literature Review

Shortly after the revolt in Syria commenced and violent clashes occurred all over the country, Western scholars already started to propose plans and scenarios for a “post-Assad Syria” (Serwer, 2012; see also Dalton, 2012). When the conflict’s trajectory started to stagnate, discourse in media and academic circles still revolved around regime change, a possible invasion, and international support for the opposition (cf. Donker & Janssen, 2011; Fontaine, 2013; Herr et al., 2019; for a comprehensive overview of the conflict see Bawey, 2016, van Dam, 2017, Helberg, 2018, and Phillips, 2020; for early assessments see Armbruster, 2013, Schneiders, 2013, and Jenkins, 2014). By the end of 2021, however, the headlines and proposals about Syria have changed. Among many Western voices, resignation can be widely observed – some even speak of a geopolitical “[d]efeat for the US [and a] win for its foes” (O’Connor, 2021; see also Hubbard, 2021). But contrary to Arab nations “that have concluded he won the brutal civil war” (Al Arabiya, 2021), the U.S. declines to normalise its relationship with Assad and some scholars even demand a renewed, determined approach to counter and eventually topple the regime (Pamuk, 2021; Lister, 2021).

Identifying why Assad — unlike many of his fellow leaders in the region — remains in power has occupied the thought and work of various scholars already during the hot phase of the conflict. Stacher (2012), as well as Bank & Edel (2015), attributed Assad’s cling to power to his capability for adaptation and change — “regime learning” that alleviates societal pressure, allows for concessions and binds decisive groups to the government. Heydemann & Leenders (2013) as well as Sika (2015) took a comparative approach and compared the case of Syria to Iran and Egypt, respectively. They ascribe Assad’s preservation of power to specific features of “Middle East authoritarianism” (Heydemann & Leenders, 2013) and differences between the two states in their respective state-formation process and constitution of the state-coercive apparatus (Sika, 2015). Sika (2015) further connects the different paths of Egypt and Syria to the varying geostrategic interests towards these states of international actors such as the EU, U.S., and regional powers like Iran and Saudi Arabia.

Already years before the uprising in Syria began, academic work specifically tailored around Bashar Al-Assad has been put forward and now serves as a rich reference for comparison with later assessments. Most notably delivered by Leverett (2005), Zisser (2007), and Bar (2006), these early portrayals still entail the scent of change, reform, and progress promised by Assad during his first years in power. In 2009, Büchs examined the resilience of Bashar and his father Hafez Al-Assad’s rule in Syria, arguing that an effective but unstable “tacit pact” between various unequal factions in the Syrian society upheld the rule of the Al-Assads since 1970 — nonetheless, this pact would not outlast Büchs’ paper for very long. Van Dam (2011) published further work about Assad’s rule during the early developments of the Arab Spring, but since Assad and the civil war still prevail a decade later, these assessments do not hold up today. A 2014 (second edition in 2016) publication by Bawey uses the inextricable link between Assad and the start, development, and tentative outcome of the conflict to illustrate the events in Syria. While Bawey produces a well-written analysis of the conflict, it lacks a certain depth when it comes to determining the decisive personal features that kept Assad in power. The most thorough, comprehensive, and for this paper certainly most relevant in-depth analysis is provided by Cabayan & Wright (2014a, 2014b), who used 124 speeches of the Syrian leader given between 2000 and 2013 to analyse the character and conduct of Assad and propose policy behaviour towards Syria based on these assessments. Among the various methods employed in the study of Cabayan & Wright, Spitaletta (2014), as the authors of this paper, conducted a leadership trait analysis of Assad. Spitaletta’s results, while congruent with many findings of this paper, are based solely on speeches by Assad. As discussed more in-depth later, since they are planned, choreographed acts, speeches do not provide the same degree of authenticity as freely conducted interviews and therefore do not allow for the same level of analytic quality when assessing leadership style. Furthermore, Spitaletta’s analysis does not cover Assad’s behaviour and personal reaction to events and developments after 2013. Thus, this paper provides a much-needed addition to the existing literature.

Methodology

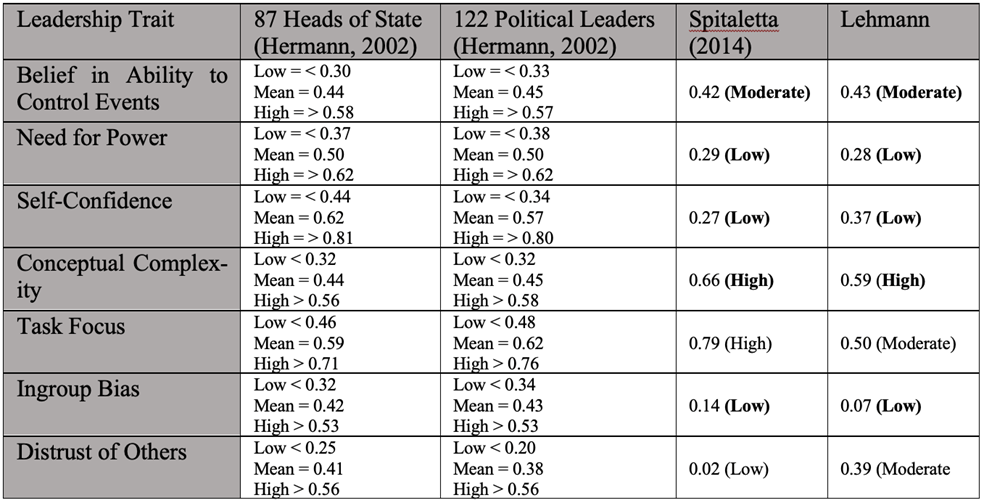

To draw conclusions about Bashar Al-Assad’s leadership style, this paper conducts a leadership trait analysis as developed by Hermann (1985; 2002) and Levine & Young (2014). For the first step of a leadership trait analysis, spoken words from a political leader’s statements, comments, and remarks are analysed according to seven personality traits. To further determine if the personality trait scores of the analysed leader are comparably low, moderate, or high, each score is compared to a databank of 87 heads of state and 122 political leaders. From this assessment, the leader’s responsiveness to constraints, openness to information, and motivation are deducted and, finally, the leadership style is determined (see Hermann, 2002, p. 9).

Although most leaders are being prepared for possible questions and corresponding answers prior to media contact, press interviews can still be considered rather spontaneous because the interviewee gives up control and must respond promptly, without time for further consultation or external aid (Hermann, 2002, p. 2). Therefore, the content and wording of ad-hoc responses allow conclusions to be drawn about what leaders are like, how they perceive themselves and others, and how they react to extrinsic factors (Hermann, 2002). Public speeches, on the other hand, are often written by hired staff, revised and amended by advisors and consultants, as well as studied and rehearsed by the leader beforehand. Hermann (1977), therefore, argues that speeches cannot be considered the outflow of a political leader’s personality and character, but rather a cautiously calculated and controlled political routine (for a thorough comparison between the quality of interviews and speeches see also Hermann, 1980; Winter et al., 1991).

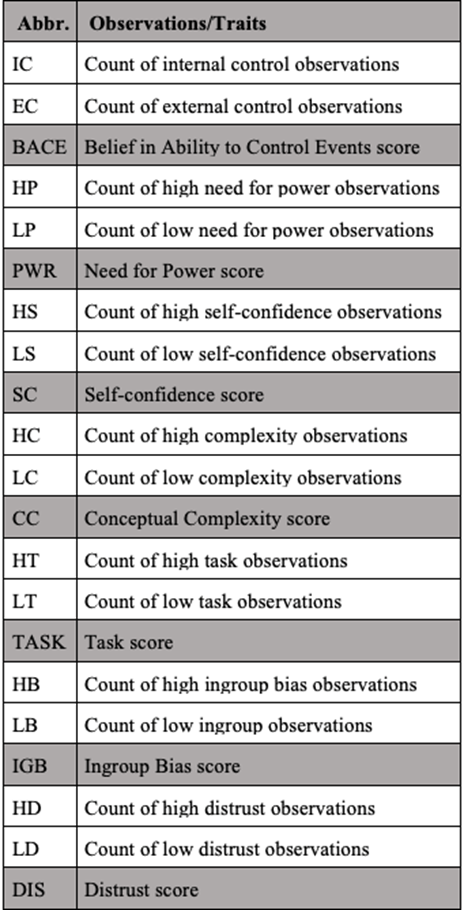

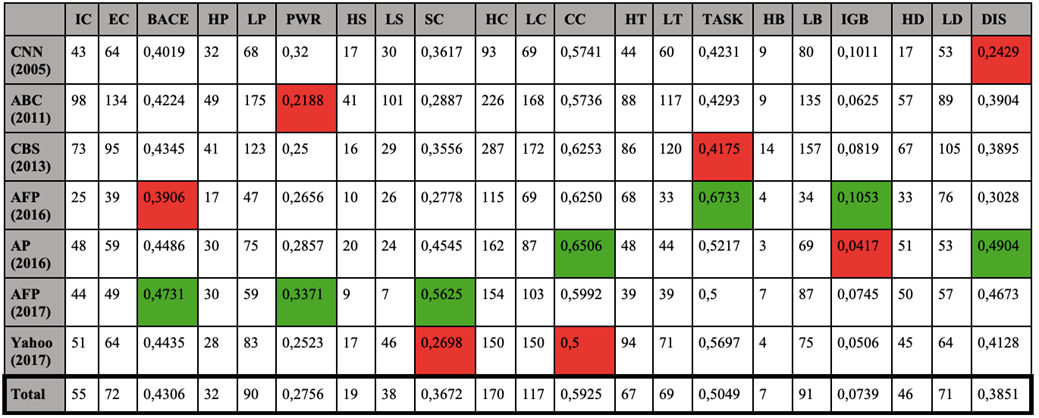

Accordingly, this analysis uses only openly conducted press interviews as its basis. While Hermann (2002) assesses that “50 interview responses of one hundred words or more in length” (p. 2) would be required to properly assess a leadership style, the authors of this analysis have used 225 interview responses of more than fifty words in length, derived from the transcripts of seven interviews with Bashar Al-Assad. The interviews were conducted between 2005 and 2017 and comprise 25.386 words (longest response = 317 words, shortest response = 52 words, average response length = 112 words). After the transcripts were thoroughly combed through, the responses were separated from the questions, converted, and analysed by the Profiler Plus software developed and provided by Young & Levine (2014). In the conducted leadership trait analysis, the frequency of specific words and phrases is considered an indicator of the degree to which a certain trait is inherent in the personality of a leader (Hermann, 2002, p. 11).

Hermann (2002, p. 3) argues that the analysed interview responses should cover various topics, different interview settings, and the leader’s whole term of office, thereby providing a general description and preventing the results from being too narrow and context-specific. The selected interviews cover 12 years and were conducted before, during, and after the Arab Spring. Furthermore, they deal with various topics from the U.S. invasion of Iraq (CNN, 2005), Assad’s personal life (ABC, 2011), the protests during the Arab Spring (ABC, 2011; CBS, 2013) to the ongoing civil war in Syria (ABC, 2011; CBS, 2013; AFP, 2016; AP, 2016; AFP, 2017; Yahoo, 2017). Because all interviews were conducted by Western journalists for Western news and broadcasting companies, this analysis is not able to provide a broad scope of audiences covered by the interview responses and its results must be considered accordingly. It can be assumed that Assad is more calculating, more considerate, and, most importantly, more controlled when speaking to Western media than he would be when speaking with a Syrian, regime-friendly newspaper. Already in 2006, Bar attested to Assad the ability to vary his conduct between Western and domestic audiences. While he attempted to gain sympathy from external actors in his “Dr Bashar” role and “convey the impressions that he is not a dictator” (Bar, 2006, p. 369), Assad portrayed a sharp contrast when being in contact with Syrians as “Mr President”. Nonetheless, because the interviews were conducted openly, question by question, and in some cases also over longer durations, they can be regarded as the richest source of insights into Assad’s thinking that is available to academics outside the Syrian regime structures.

Analysis

According to Hermann (2002, p. 5), leadership style describes how leaders relate to their surroundings, which principles, rules, and norms they adhere to, as well as the way they conduct interactions with other leaders, advisors, elite groups, and their constituents. In the following, we will determine Bashar Al-Assad’s leadership style by assessing how he reacts to constraints, how open he is to incoming information, and what his motives are for seeking office and remaining in power.

Responsiveness to Constraints

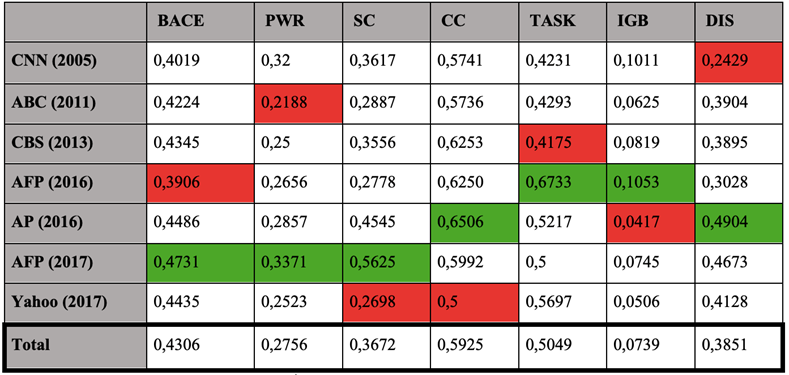

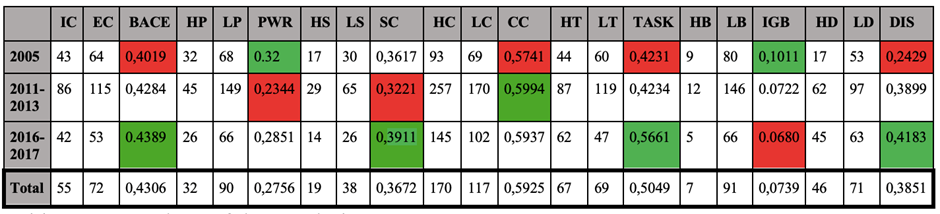

To evaluate if he rather challenges or respects constraints, we will first analyse Assad’s belief in his ability to control events as well as his need for power. The belief to be able to control events represents the degree to which leaders perceive that they possess a certain control over the events and situations that surround them and assume to be able to influence such matters (Hermann, 2002, pp. 13-14). When determining leaders’ perception of their ability to control events, it is evaluated how often during an interview the responsibility for planning or executing an action is taken over by the leader or a group they identify with by assessing the frequency of action words and verbs that signal such behaviour (Hermann, 2002, p. 14). With an average of 55 internal control observations and 72 external control observations per interview, Bashar Al-Assad scores an average of 0.43 for the belief in his ability to control events (see Appendix A). Compared to the databank of 87 heads of state (x̄ = 0.44) and 122 political leaders (x̄ = 0.45), Assad’s score ranges slightly below the general mean (see Appendix B). It can be observed that he depicted the highest level of belief to be able to control events (0.47) in 2017 in his interview with AFP and the lowest level (0.39) in 2016 in another interview with AFP (for differences in answering behaviour see Appendix C). According to Hermann (2002, p. 15), leaders who do not have a strong belief that they can control events are rather reactive, reluctant to act first, and often less likely to take over the initiative.

Already in 2005, Leverett points out Assad’s awareness of constraints on his power and capability to shape events in Syria. He argues that Assad “sees himself as constrained (…) and openly acknowledges his need for external support to improve (…) implementation of reform initiatives and policies“ (Leverett, 2005, p. 82). Leverett (2005) further emphasises Assad’s “self-acknowledged constraints“ (p. 98) and that he recognises deficiencies in his ability to achieve policy goals due to limitations in the system of governance and power structures of Syrian agencies and ministries. This point of view is supported by Jenkins (2014), who argues that Assad was aware of his lack of control over foreign volunteers, regime-friendly militias, and Hezbollah fighters. In Spitaletta’s (2014) leadership trait analysis of Assad, the Syrian leader scores 0.42 for his belief to be able to control events. Diverging only 0.01 from our result, Spitaletta (2014) concludes that Assad is “unlikely to be overly proactive or reactive in policy-making” (p. 73).

The need for power and influence signals a leader’s determination to establish, maintain, or restore the power needed to secure that very leadership position — or, as Winter (1973) puts it, to have “control of the means of influence” (p. 57) and impact the action and volition of individuals or groups. When coding an interview for a leader’s need for power, the frequency of verbs is determined which signal that a leader proposes forceful action, engages in arguments, accusations, threats, unsolicited advice, worries about their position or reputation, or tries to actively control the behaviour of others (Hermann, 2002, p. 15). With a mean of 32 high need for power observations and 90 low need for power observations per interview, Assad scores an average of 0.28 when it comes to his need for power (see Appendix A). Compared to the 87 heads of state (x̄ = 0.5) and 122 political leaders (x̄ = 0.5), his score is considered low (< 0.37) (see Appendix B). It can be observed that he depicted the highest level of need for power (0.34) in 2017 in his interview with AFP and the lowest level (0.22) in 2011 with ABC (see Appendix C). Hermann (2002) assesses that leaders without a high need for power “have less need to be in charge; they can be one among several who have influence” (p. 17) and often become agents for their group, advocating for and representing their positions in policy-making.

Our result is congruent with the literature and supported by various authors over the years. In 2004, Wieland quoted Syrian actors who called Assad a „junior partner” (p. 56) in the Syrian power structure as well as a “prisoner of his power clique” (p. 103). Bar (2006) extends these claims, arguing that the remains of his father’s regime – the “old guard” – still constituted the main policy driver at the time and no specific policies could be attributed “to Bashar alone or to his overruling of others“ (p. 369). While Bar (2006, p. 374) acknowledges that the survival of his regime is the top priority for Assad, he argues that Assad does not insist on pursuing this objective solely on his terms but instead delegates authority, and consults experts on various matters, and rarely takes decisions alone. Phillips (2020) observed this tendency also during the height of the protests and civil war, during which “Assad did not want to get his hands dirty [and] delegated authority for the crackdown” (p. 14) to military and intelligence leaders. Although the presence and influence of the “old guard” during the early years of the Assad reign is not contested, various authors describe that over time, Assad attempted to rid his government of these influences, removed many of the former key actors, and expanded his range of power (Bar, 2006, p. 374; Zisser, 2007, p. 64; extensively in Ziadeh, 2011; Van Dam, 2017). The decentralised distribution of power in the Syrian state apparatus and the resulting necessity for Assad to share influence and power among various actors is further described by Van Dam (2017, p. 105), who regards a handful of military leaders from various branches of the army as the most important contestants for Assad’s claim to power (see also Stacher, 2012; Scheller, 2014, p. 45). Borshchevskaya (2022, p. 154) also regards Russian president Putin to be a major influence and competitor to Assad’s ability to wield power on his own, claiming that Syria’s dependence on Russian financial and military aid gives Putin significant leverage over decision-making in Damascus. Helberg (2018) further supports these assessments by arguing that Assad, contrary to his father, lacks an “extraordinary instinct for power” (p. 16). Spitaletta’s (2014) assessment of Assad’s need for power (0.29) is again coherent with our result and he concludes that Assad “has less of a need to be in charge and may be more amenable to subordinates assuming more prominent roles” (p. 75).

Since Assad believes that he can control events only to a less than average degree and depicts a low need for power, he will be considered low on both traits. Hermann (2002, p. 13) argues that someone low on both traits respects constraints, works within these towards their goals, and holds consensus and compromise in high regard.

Openness to Contextual Information

To determine Assad’s openness to external input in the decision-making process, his level of self-confidence and conceptual complexity is assessed. Self-confidence as a personality trait indicates a leader’s sense of self-importance and if they perceive themselves to be able to properly deal with individuals and objects in their surroundings (Hermann, 2002, p. 20). The focus during the coding for self-confidence lies on the connection of a leader’s personal pronouns to the engagement in an activity, the proclamation of authority, or the reception of positive responses from outside groups (Hermann, 2002, p. 21). Averaging 19 high self-confidence observations and 38 low self-confidence observations per interview, Bashar Al-Assad scores an average of 0.37 for his self-confidence (see Appendix A). Compared to the databank of 87 heads of state (x̄ = 0.62) and 122 political leaders (x̄ = 0.57), Assad’s score of 0.37 ranges low among the heads of state (< 0.44) and only slightly above a low classification among the political leaders (< 0.36) (see Appendix B). He depicted the highest level of self-confidence (0.56) in 2017 in his interview with AFP and the lowest level (0.27) in 2017 with Yahoo (see Appendix C). Hermann (2002, p. 21) states that leaders with low self-confidence tend to be highly influenced by changing circumstances and shifts of opinion in their environment. Because they are unsure about the paths to pursue, these leaders seek feedback, information, and opinions from others and tend to act inconsistently — depending on the setting, audience, and surroundings (Hermann, 2002, p. 22).

Our assessment of Assad’s self-confidence is supported by a consistent and uniform image of the leader, conveyed through various sources between 2004 and 2020. Assad is portrayed as a leader who “knows about his weaknesses“ (Wieland, 2004, p. 92), “is acutely aware of his leadership deficiencies“ (Bar, 2006, p. 370), lacks “the image of a charismatic, capable leader“ (Zisser, 2007, p. 29), has an “obvious absence of experience and self-confidence“ (Zisser, 2007, p. 43; also Bar, 2006, p. 377), and, according to an account by former U.S. ambassador Robert S. Ford, Assad has “such a weak personality” (Phillips, 2020, p. 18). Resulting of this lack of self-confidence, Assad relied on others for guidance and advice from early on. Starting with the “old guard”, followed by new advisors and technocrats of his own choosing, and now Syrian military leaders as well as Russia and Iran — Assad remains in need of others. With a score of 0.27, Spitaletta’s (2014) analysis yields an even lower evaluation of Assad’s self-confidence than our paper does. Nonetheless, both leadership analyses of Assad correspond with the consistent picture depicted of the leader in the pertinent literature.

Conceptual complexity describes the level of differentiation that a leader is able to employ when contemplating “other people, places, policies, ideas, or things” (Hermann, 2002, p. 22). To determine the level of conceptual complexity, specific words are coded that indicate a leader’s ability to detect multiple dimensions of a single affair (for examples see Hermann, 2002, p. 22; for an exhaustive list see Levine & Young, 2014). By averaging 170 high complexity observations and 117 low complexity observations per interview, Assad scores an average of 0.59 for contextual complexity (see Appendix A). Compared to the databank of 87 heads of state (x̄ = 0.44) and 122 political leaders (x̄ = 0.45), Assad’s score of 0.59 ranges high among both sample groups (> 0.56 and > 0.58 respectively) (see Appendix B). He showed the highest level of contextual complexity (0.65) in 2016 in his interview with AP and the lowest level (0.5) in 2017 with Yahoo (see Appendix C). Leaders that express a high degree of contextual complexity take in a wider scope of arguments and are capable to see issues from various perspectives (Hermann, 2002, p. 23). Hermann (2002, p. 23) also argues that these leaders often take their time in the decision-making process to be able to consider eventual outcomes and possible alternatives – they tend to not trust initial responses but rather try to maintain flexibility and be prepared for new insights.

The relevant literature supports such an evaluation and describes Assad as someone who does not take decisions “impulsively or without careful assessment, calculation, and preparation for the long-range implications“ (Bar, 2006, p. 367) and has an “inclination toward an analytical, rational and methodical approach“ (Zisser, 2007, pp. 19-20) when dealing with challenges. Even during the rapid developments early in the uprisings of the Arab Spring, Assad delayed an address to the nation for a week to reportedly gather facts and consult about the events on the streets before formulating his position (Phillips, 2020, p. 30). Assad’s high capability to differentiate and change perspectives is also often attributed to his vast exposure to Western ideals and values during his time as a doctor in Europe and due to his wife being born and raised in London (Zisser, 2007, pp. 22, 25). Being the former chair of the Syrian Computer Society, declaring himself to be a jazz fan, and intentionally cultivating an image of Syrian cosmopolitanism and orientation towards culture and arts led to Assad being conceived as a “Westernised” leader rather than one being driven by traditional values (Zisser, 2007, p. 130; Heydemann & Leenders, 2013, p. 23). He, furthermore, conducted extensive visits to Arab and Western European countries to meet other leaders personally and gather first-hand experiences about narratives and perceptions abroad (Zisser, 2007, p. 131). This viewpoint of Assad is contested by Van Dam (2017), who believes these evaluations to be rather “based on wishful thinking than on realities” (p. 85) and drastically exaggerated. Spitaletta’s (2014) assessment of Assad’s contextual complexity (= 0.66), although ranging 0.07 higher, yields the same classification as ours.

Since Assad showed low self-confidence but a high degree of conceptual complexity, he can be considered a leader that is open to contextual information. Such leaders, according to Hermann (2002, p. 18), are often responsive to the needs and interests of others and seem to conduct themselves in a more pragmatic fashion than others. Furthermore, they often handle events and issues case by case and tend to evaluate what actions they perceive to be acceptable in a situation prior to executing them (Hermann, 2002).

Motivation for Seeking Office

Lastly, it is necessary to determine the underlying reason for Assad to assume, remain in, and defend his position of power. To assess if he is either driven by internal motivations (e.g., particular interests, ideologies, or a specific cause) or by the desired reaction from his environment (e.g., support, power, approval), we will evaluate Assad’s motivation for seeking power as well as his identification with the group he belongs to (cf. Hermann, 2002).

When examining the motivation of a leader to seek office, we distinguish between different group functions that a leader can fulfil “maintaining group spirit and morale” (Hermann, 2002, p. 24) or pushing the group to pursue a task. To assess if leaders are such “relationship-builders” or “problem-solvers”, it is observed if they focus rather on the emotions and desires of relevant constituents or on interactions with other individuals. If words signal pursuing an activity or working on a task, they are counted as indicators for a task orientation. Meanwhile “words that center around concern for another’s feelings, desires, and satisfaction” (Hermann, 2002, p. 26) signal an orientation towards relationships. Averaging 67 high task observations and 69 low task observations per interview, Assad shows an average of 0.50 for his task orientation (see Appendix A). Compared to the databank of 87 heads of state (x̄ = 0.59) and 122 political leaders (x̄ = 0.62), a score of 0.50 ranges moderate among both sample groups (see Appendix B). He showed the highest degree of task focus (0.67) in 2016 in his interview with AFP and the lowest level (0.42) in 2013 with CBS (see Appendix C). Some scholars (e.g., Bass, 1981) argue that leaders with a moderate task focus are often charismatic by nature and — depending on the context — can focus on fostering relationships if appropriate or on problem-solving if necessary.

There is little evidence in the existing literature to confirm or refute such an assessment, but Bar argued in 2006 that Assad was well aware of the expectations and demands of the Syrian population and even interested in fulfilling them. Leverett (2005) also confirms that Assad’s task orientation in his early years was not particularly prominent due to a lack of “capacity or ultimate intention“ (p. 69) to solve social issues. Assad’s awareness of the relationship with his constituents is again reported by Phillips (2020, p. 24), who points out that during the early days of protests in Daraa, Assad attempted conciliation, tried to defuse tensions, and integrate community leaders into settlements with protestors. Contrary to our assessment, Spitaletta (2014) considers Assad to possess a very high task orientation (0.79) — a result not supported by other sources.

The personality trait of ingroup bias describes if and to what degree a leader’s worldview is occupied and impacted by a group affiliation (Hermann, 2002, p. 29). Hermann (2002) argues that intense and long-lasting attachments can exist between a leader and an ingroup and that the leader will put an emphasis on maintaining the culture and status of his group. When analysing the interviews, it is observed if words or phrases referring to the leader’s group are “favorable (…); suggest strength (…); or indicate the need to maintain group honor and identity” (Hermann, 2002, p. 29). When coding for ingroup bias, an average of only 7 high ingroup bias observations and 91 low ingroup bias observations per interview could be determined. Assad, therefore, scores an average of 0.07 for ingroup bias (see Appendix A). Compared to the databank of 87 heads of state (x̄ = 0.42) and 122 political leaders (x̄ = 0.43), Assad’s score of 0.07 for ingroup bias ranges far below what is classified as a low degree (< 0.32 and < 0.34 respectively) (see Appendix B). He showed the highest level of ingroup bias (0.11) in 2016 in his interview with AFP and the lowest level (0.04) in 2016 with AP (see Appendix C). According to Hermann (2002, p. 30), leaders with a low ingroup bias tend to see cleavages between groups as less rigid but are nonetheless concerned with maintaining their respective group. Such a differentiated perspective on friend and foe allows leaders to react and adapt more freely to the context and events in their environment (Hermann, 2002, p. 30).

While Assad’s reliance on the structures and power base of the Ba’th Party is uncontested, many sources confirm our evaluation that Assad does not possess an exaggerated ingroup bias but is able to rely on outsiders if it suits his interests, and thus, can adapt faster and more freely to changes in his surroundings. Assad has shown that he can strengthen and use the influence of party cadres while at the same time inserting external experts and technocrats into key positions in government (Bar, 2006, p. 362). This employment of the party as a powerful platform, while simultaneously fostering the careers of non-Ba’th experts, as observed by different authors, resulted in the strengthening of his own position — disliked cadres are alienated while favorable outsiders gain influence (Bar, 2006, p. 374; Sika, 2015, p. 165). Another group that Assad belongs to, but towards which he remains at a calculated distance, are the Alawites. Neither did he marry a woman of Alawite origin (Asma Al-Assad is from a Sunni family), nor did he “attach sufficient importance to entrenching his regime on firm clan, tribal and communal foundations“ (Zisser, 2007, pp. 58, 62-63). Since the ruling, Alawites see themselves confronted with a predominantly Sunni population, and the possibility of Assad’s demise has stoked fears of violent repercussions among their communities early on — realising they need Assad more than he needs them (Bawey, 2014, pp. 24, 49). Spitaletta (2014) also determined a low ingroup bias score for Assad (0.24), and thus, further supports our assessment.

As the last personality trait, a leader’s distrust of others is analysed. Such distrust can be ascertained if leaders possess a “general feeling of doubt, uneasiness, misgiving, and wariness about others” (Hermann, 2002, p. 30), as well as when they show the tendency to suspect actions and speculate about the motives of others. To establish the degree of distrust, interview responses are perused for statements towards individuals or groups external to the analysed leaders and their surroundings that indicate “distrust, doubt, misgivings or concern about what these persons or groups are doing” (Hermann, 2002, p. 10). By averaging 46 high distrust observations and 71 low distrust observations per interview, Assad scores an average of 0.39 for distrust towards others (see Appendix A). Compared to the databank of 87 heads of state (x̄ = 0.41) and 122 political leaders (x̄ = 0.38), Assad’s score of 0.39 is considered moderate (see Appendix B). He showed the highest level of distrust of others (0.49) in 2016 in his interview with AP and the lowest level (0.24) in 2005 with CNN (see Appendix C). Leaders with a moderate distrust of others are neither overly suspicious, paranoid or obsessed with loyalty nor do they take relationships and trust likely (Hermann, 2002, p. 31-32). Spitaletta’s (2014) analysis yielded a distrust score of 0.024, significantly lower than our assessment. The existing literature does not provide reliable insights to prove or refute either result, therefore, further investigation into Assad’s actual trust behaviour towards others is needed.

Since Assad has a low ingroup bias and a moderate distrust of others, his focus is on building relationships and seizing opportunities, while, at times and depending on the context, remaining vigilant towards his surroundings (Hermann, 2002, p. 28).

Comparison

Having thoroughly assessed Assad’s personality traits, compared the findings with other leaders, and put the results into context, it is further necessary to briefly analyse the changes in Assad’s answering behaviour and determine how these developments fit into the temporal context. To that end, the interviews used for this analysis are separated according to the time periods they were published (see Appendix D). The CNN interview from 2005 is used as a pre-Arab Spring reference, the interviews from 2011-2013 are used to depict Assad’s personality traits during the emergence, escalation, and height of the violence, and the interviews from 2016-2017 portray a time during which conflict prevailed but the survival of the regime seemed secure.

When comparing Assad’s results over these three periods, a few striking observations can be made. Assad’s distrust of others (from 0.24 in 2005 to 0.42 in 2016-2016), as well as his task focus (from 0.42 to 0.57), have increased most significantly. Being surrounded by enemies, ostracised in the international community, and afflicted by desertion, Assad must have realised that he can only rely on and trust in himself and his immediate surroundings. Furthermore, he recognised that he must face and ultimately overcome the challenges ahead with determined action – carefully attempting to foster relationships might prove inadequate when opposition forces have already seized the outskirts of your capital.

While his self-confidence has increased overall (0.36 to 0.39), it suffered a downturn during the height of the conflict (0.32). Because these interviews were conducted during a time in which his regime’s survival was far from certain, it is not farfetched to attribute this outlier to an uncertain future and concerns about the security of his regime, his family, and his life.

Assad’s belief to have the ability to control events has increased only slightly since 2005 (0.40 to 0.44), as has his conceptual complexity (0.57 to 0.59). His need for power on the other hand has decreased slightly (0.32 to 0.29), similar to his already low ingroup bias (0.10 to 0.07). Such nearly consistent observations that signal only minor changes over a long period of time serve as an indication of the quality of our findings and suggest that Assad possesses a consolidated personality in these aspects.

Conclusion

Our analysis has shown that Bashar Al-Assad respects constraints in his environment and works within these towards his goals. Among the actors and groups that Assad depends on or feels attached to, he values consensus and compromise. Furthermore, he is open to contextual information, and therefore, is more responsive to the needs and interests of others. Moreover, he is more pragmatic than other leaders, rather tends to handle issues case by case, and evaluates how actions are perceived by others prior to carrying them out. Depending on the context, his focus is either on building relationships or on seizing opportunities to solve problems.

According to Hermann (2002), leadership style is derived from a combination of a leader’s responsiveness to constraints, openness to information, and motivation for seeking office. Utilising this classification and applying it to the results of this analysis, Assad can be categorised as having either a reactive or accommodative leadership style, depending on the context. While reactive leaders focus on evaluating their possibilities in a given situation and consider which options important actors will favour or allow, accommodative leaders focus on building consensus in their environment, empowering others, sharing accountability, and reconciling differences (Hermann, 2002, p. 9).

This classification can help us to explain why Assad, unlike many of the leaders during the Arab Spring, is still in power a decade later. For one, he managed to restrain his ambitions and harmonise the means to his disposal with the ends he pursued. When a leader desires more than his resources allow, he will ultimately fail. But if he desires less than he can achieve, he will not reach his full potential. Assad knew his constraints and acted only when he was at an advantage, thereby he prevented overstretching his capabilities and wearing out his armed forces. Secondly, Assad made himself aware of the implications of his own actions on other actors. Skilfully, he combined Russian and Iranian resources to command an army of Alawites, Druzes, Christians, Kurds, and even Sunnis against a common enemy – all while balancing their interests against his own. Arguably, the loss of only one of these groups or allies could have caused significant harm, if not the downfall of the regime. Lastly, Assad did not refrain from sharing authority and power among important actors and allies. Without the Syrian security and intelligence apparatus as well as influential military leaders, he would arguably not have remained in power to this day. While other states saw the military and police switching sides during the Arab Spring — the ultimate demise for a ruler — the Syrian army and intelligence agencies remained loyal and consequently kept the regime alive.

In conclusion, Assad’s grip on power cannot be attributed to particularly exceptional and outstanding character traits, but to perseverance and the ability to adapt quickly and stay flexible, as well as to take into account the perspectives of others. His analysed character traits, some of which place rather below average, thus, suggest an ordinary and versatile leader who, instead of being distinguished by striking and memorable unique features, is rather characterised by the unification of extremes: from mediocrity to success.

As stated above, the authors of this paper only used interviews from Western sources between 2005 and 2017. Further and future research, therefore, needs to expand the data sources to also include Arabic interviews that cover earlier as well as later years and, to refine the results, use only longer responses (80 words or more). While our results are very similar to Spitaletta’s (2014), it is necessary to conduct further independent leadership trait analyses of Bashar Al-Assad and, by comparing data and methodology, assess the quality of each study’s results. Lastly, post-civil war analyses could provide additional references in the future and put results from during the civil war, such as this paper, into perspective.

Appendix

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

Appendix D

Bibliography

ABC (2011). TRANSCRIPT: ABC’s Barbara Walters’ Interview With Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. ABC News December 6, 2011. Accessible online at: https://abcnews.go.com/International/transcript-abcs-barbara-walters-interview-syrian-president-bashar/story?id=15099152

AFP (2016). Transcript of exclusive AFP interview with Syria’s Assad. Justice Info. February 12, 2016. Accessible online at: https://www.justiceinfo.net/en/26000-transcript-of-exclusive-afp-interview-with-syria-s-assad.html

AFP (2017). Transcript of exclusive AFP interview with Syria’s Assad. The Peninsula. April 13, 2017. Accessible online at: https://m.thepeninsulaqatar.com/article/13/04/2017/Transcript-of-exclusive-AFP-interview-with-Syria-s-Assad-1

Al Arabiya News (2021) US rules out normalizing with Syria’s Assad. Al Arabiya News. 14.10.2021. Retrievable online at: https://english.alarabiya.net/News/middle-east/2021/10/14/US-rules-out-normalizing-with-Syria-s-Assad Last access: 14.10.2021

Al Jazeera (2017) Leaders in the Arab Spring era: Where are they now? Al Jazeera. 04.12.2021. Retrievable online at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/12/4/leaders-in-the-arab-spring-era-where-are-they-now Last access: 14.10.2021.

AP (2016). Full transcript of AP interview with Syrian President Assad. The Associated Press. September 22, 2016. Accessible online at: https://apnews.com/article/c6cfec4970e44283968baa98c41716bd

Armbruster, J. (2013). Brennpunkt Nahost: Die Zerstörung Syriens und das Versagen des Westens (1. Aufl.). Westend.

Bank, A., & Edel, M. (2015). Authoritarian Regime Learning: Comparative Insights from the Arab Uprisings. German Institute of Global and Area Studies (GIGA). Accessible online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep07503

Bar, S. (2006). Bashar’s Syria: The Regime and its Strategic Worldview. Herzliya: Institute for Policy and Strategy.

Bass, B. M. (1981). Stogdill’s Handbook of Leadership. New York: Free Press.

Bawey, B. (2014). Assads Kampf um die Macht: 100 Jahre Syrienkonflikt. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Bawey, B. (2016). Assads Kampf um die Macht: Eine Einführung zum Syrienkonflikt. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Borshchevskaya, A. (2022). Putin’s War in Syria: Russian Foreign Policy and the Price of America’s Absence. London: I.B. Tauris.

Büchs, A. (2009). The Resilience of Authoritarian Rule in Syria under Hafez and Bashar Al-Asad. German Institute of Global and Area Studies (GIGA). Accessible online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep07504

Cabayan, H., & N. Wright (Eds.) (2014a). A multi-disciplinary, multi-method approach to leader assessment at a distance: The case of Bashar al-Assad, Part I: Summary, comparison of results, and recommendations. Strategic Multilayer Assessment February 2014. Accessible online at: http://socialscience.net/docs/alAssadPartIApril2014.pdf

Cabayan, H., & N. Wright (Eds.) (2014b). A multi-disciplinary, multi-method approach to leader assessment at a distance: The case of Bashar al-Assad, Part II: Analytical Approaches. Strategic Multilayer Assessment February 2014. Accessible online at: http://socialscience.net/docs/alAssadPartIIApril2014.pdf

CBS (2013). Transcript of Bashar Al-Assad’s interview with CBS. The Syrian Observer. September 10, 2013. Accessible online at: https://syrianobserver.com/interviews/34692/president_assads_interview_with_american_cbs_news.html

CNN (2005). Al-Assad: ‘Syria has nothing to do with this crime’. CNN October 12, 2005. Accessible online at: https://edition.cnn.com/2005/WORLD/meast/10/12/alassad.transcript/

Dalton, M. G. (2012). Asad Under Fire: Five Scenarios for the Future of Syria. Center for a New American Security. Accessible online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep06174

Donker, T. H., & Janssen, F. (2011). Supporting the Syrian Summer: Dynamics of the Uprising and Considerations for International Engagement. Clingendael Institute. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep05343

Fontaine, R. (2013). The President is Right to Intervene, but Then What? Center for a New American Security. Accessible online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep06238

Helberg, K. (2018). Der Syrien-Krieg: Lösung eines Weltkonflikts. Freiburg: Verlag Herder.

Hermann, M. G. (1977). A Psychological Examination of Political Leaders. New York: Free Press.

Hermann, M. G. (1985) Validating a Technique for Assessing Personalities of Political Leaders at a Distance: A Test Using Three Heads of State. Report prepared for Defense Systems, Inc.

Hermann, M. G. (1980). Explaining Foreign Policy Behavior Using the Personal Characteristics of Political Leaders. International Studies Quarterly, 24, 7-46.

Hermann, M. G. (2002). Assessing Leadership Style: A Trait Analysis. Slingerlands, NY: Social Science Automation.

Herr, L. D., Müller, M., Opitz, A., & Wilzewski, J. (2019). Weltmacht im Abseits: Amerikanische Außenpolitik in der Ära Donald Trump. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

Heydemann, S., & Leenders, R. (2013). Middle East Authoritarianisms: Governance, Contestation, and Regime Resilience in Syria and Iran. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Holmes, O. (2020). Arab spring autocrats: The dead, the ousted and those who remain. The Guardian 14.12.2020. Accessible online at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/dec/14/arab-spring-autocrats-the-dead-the-ousted-and-those-who-survived Last access: 14.10.2021.

Hubbard, B. (2021) Bashar al-Assad Steps In From the Cold, but Syria Is Still Shattered. New York Times 11.10.2021. Accessible online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/11/world/middleeast/al-assad-syria.html Last access: 14.10.2021.

Jenkins, B. M. (2014). The Dynamics of Syriaʹs Civil War. RAND Corporation. Accessible online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep02450

Leverett, F. (2005). Inheriting Syria: Bashar’s Trial by Fire. Brookings Institution Press.

Levine, N., and M. D. Young (2014). Leadership Trait Analysis and Threat Assessment with Profiler Plus. Proceedings of ILC 2014 on 8th International Lisp Conference, Montreal, QC, Canada — August 14-17, 2014. Association for Computing Machinery.

Lister, C. (2021) Biden’s Inaction on Syria Risks Normalizing Assad—and His Crimes. Foreign Policy 08.10.2021. Retrievable online at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/10/08/biden-syria-policy-assad-war-crimes/ Last access: 14.10.2021.

O’Connor, T. (2021) Syria’s Bashar al-Assad Returns to World Stage in Defeat for US, Win for its Foes. Newsweek 13.10.2021. Retrievable online at: https://www.newsweek.com/2021/10/22/syrias-bashar-al-assad-returns-world-stage-defeat-us-win-its-foes-1637831.html Last access: 14.10.2021.

Pamuk, H. (2021) Blinken says U.S. does not support normalisation efforts with Syria’s Assad. Reuters 13.10.2021. Retrievable online at https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/blinken-says-us-does-not-intend-normalize-relations-with-syrias-assad-2021-10-13/ Last access: 14.10.2021.

Phillips, David L. (2020). Frontline Syria: From Revolution to Proxy War. London: I.B. Tauris.

Scheller, B. (2014). The Wisdom of Syria’s Waiting Game: Foreign Policy under the Assads. London: C. Hurst & Co.

Schneiders, T. G. (2013). Der Arabische Frühling: Hintergründe und Analysen. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Serwer, D. (2012). Post-Asad Syria. PRISM 3(4), 2–11. Accessible online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/26469757

Sika, N. (2015). Arab States, Regime Change and Social Contestation Compared: the Cases of Egypt and Syria. In The Arab Uprisings: Transforming and Challenging State Power, E. Kienle and N. Sika (eds.), 158–175. London and New York: I.B. Tauris.

Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (SOHR) (2021). Total death toll | Over 606,000 people killed across Syria since the beginning of the “Syrian Revolution”, including 495,000 documented by SOHR. SOHR June 1, 2021. Accessible online at: https://www.syriahr.com/en/217360/

Spitaletta, J. (2014). Approach 3: Leadership Trait Analysis. In A multi-disciplinary, multi-method approach to leader assessment at a distance: The case of Bashar al-Assad, Part II: Analytical Approaches, H. Cabayan & N. Wright (Eds.), 62-77. Accessible online at: http://socialscience.net/docs/alAssadPartIIApril2014.pdf

Stacher, J. (2012). Adaptable Autocrats: Regime Power in Egypt and Syria. Stanford University Press.

van Dam, N. (2011). The struggle for power in Syria: politics and society under Asad and the Ba’th Party. London: I.B. Tauris.

van Dam, N. (2017). Destroying a nation: the civil war in Syria. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Wieland, C. (2004). Syrien nach dem Irak-Krieg: Bastion gegen Islamisten oder Staat vor dem Kollaps?. Berlin: Klaus Schwarz Verlag.

Yahoo (2017). Full interview transcript: Syrian President Bashar Assad. Yahoo February 10, 2017. Accessible online at: https://www.yahoo.com/news/full-interview-transcript-syrian-president-bashar-assad-194809125.html?soc_src=social-sh&soc_trk=ma

Ziadeh, R. (2010). Power and policy in Syria: Intelligence services, foreign relations and democracy in the modern Middle East. London: I.B. Tauris.

Zisser, E. (2007). Commanding Syria: Bashar al-Asad and the first years in power (First edition.). London: I.B. Tauris.

Zisser, E. (2011). The Syria of Bashar al-Asad: At a Crossroads. Institute for National Security Studies. Accessible online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep08826

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Assessing Syria’s Chemical Weapons Ambiguity

- Offensive Realism and the Rise of China: A Useful Framework for Analysis?

- Globalisation, Agency, Theory: A Critical Analysis of Marxism in Light of Brexit

- Two Nationalists and Their Differences – an Analysis of Trump and Bolsonaro

- The European Quality of Government Index: A Critical Analysis

- Beyond Black Flags: Daesh as a Framework for Strategic Identity Analysis