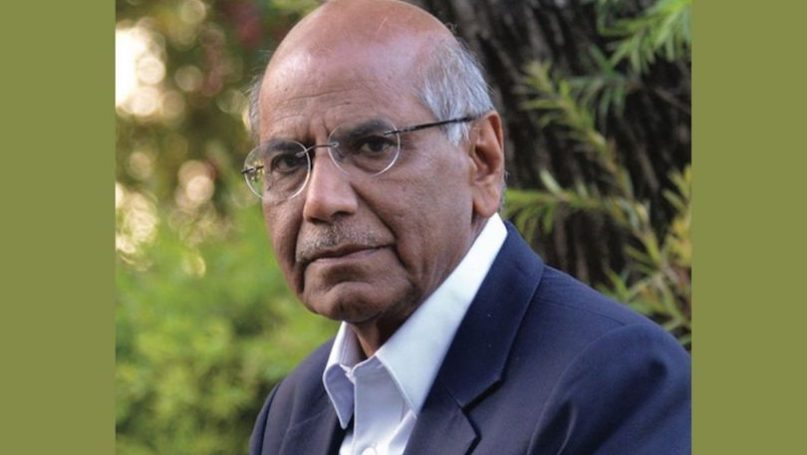

Shyam Saran is a career diplomat. Since joining the Indian Foreign Service in 1970, he has served in several capitals of the world including Beijing, Tokyo, and Geneva. He has been India’s Ambassador to Myanmar, Indonesia and Nepal and High Commissioner to Mauritius. After a career spanning 34 years in the Indian Foreign Service, Saran was appointed India’s Foreign Secretary in 2004 and held that position till his retirement from service in September 2006. After his retirement, he was appointed Prime Minister’s Special Envoy for Indo-US civil nuclear issues and later as Special Envoy and Chief Negotiator on Climate Change. He has now concluded his assignment in Government and returned to being a private citizen. He is also Senior Fellow with the Centre for Policy Research, a prestigious think tank. Shyam Saran is President of the India International Centre. He speaks and writes regularly on a variety of subjects. His book, How India Sees the World was published in September 2017. He has recently published his second book, How China Sees India and the World. Saran holds a post-Graduate degree in Economics. He speaks Hindi, English and Chinese and is conversant in French.

Where do you see the most exciting research/debates happening in your field?

The most important influence on international relations is technology, in particular the impact of digital technology. The pandemic has accelerated the spread of digital technology and enabled diplomacy in the virtual space, including the convening of summit meetings among leaders and the holding of online conferences and meetings. There is very little study of the ways in which inter-state relations have been affected by these developments. We now have the phenomenon of “twitter diplomacy” which is changing the nature of diplomatic interactions with the premium on instantaneity, rather than the traditional carefully deliberated and mediated communications. This has added complexity to the whole field of international relations and offers a rich field for research.

How has the way you understand the world changed over time, and what (or who) prompted the most significant shifts in your thinking?

Since the world itself has changed in dramatic ways as has India itself, it is inevitable that one’s thinking about international relations, too, would change in fundamental ways. We live in a more globalized and densely inter-connected world and the dividing line between what is domestic and what is external has changed. The external environment impinges on our ability to tackle domestic issues; equally choices which India makes in its pursuit of economic and social development, affect the prospects for tackling global issues. For example, the energy choices which India makes, the extent to which it chooses to meet its energy security needs through renewable energy or through continued reliance on fossil fuels, will affect the world’s ability to tackle Climate Change because India, even as a developing country has a large energy footprint. It is also true that even if India achieved zero carbon emissions tomorrow by some miracle, Climate Change would continue to impact India adversely unless other major energy users reduce their carbon footprint significantly. Therefore, Indian diplomacy confronts a more complex international landscape with no easy answers.

What do you see as the most crucial element in negotiation with the Chinese government given their recent turn to ‘wolf-warrior’ diplomacy?

There is no such thing as a single “crucial element” in negotiations with any state including China. One needs to explain why China has adopted a more assertive and sometimes aggressive stance in its interactions with other countries. Quite simply it reflects a Chinese perception that the balance of power has moved decisively in its favour as a result of its steady and significant accumulation of economic, military, and technological capabilities, reducing its power asymmetry with its peer rival the U.S. Conversely, the power asymmetry with India has been expanding. China believes that it is in a position to expand its influence both in Asia and the world at the cost of the existing powers. It also has less incentive to be sensitive to India’s concerns and interests. In negotiating with such a China, it is important to understand this context, maintain a firm but prudent posture and explore what countervailing initiatives need to be taken to restrain China’s unilateral assertion of power. The Quad, composed of the U.S., India, Japan, and Australia, all of whom share concerns about rising Chinese influence, is certainly a part of this countervailing strategy. Eventually, however, the answer to the China challenge is the accelerated build-up of India’s own capabilities in the economic, military, and technological fields, which is eminently possible if the right decisions are taken now. It is also my sense that in the aftermath of the Ukraine war, China is somewhat on the defensive, because of its bet on Russia as a strong ally looks to have soured.

When countries like India and China interact with the West, they tend to have a very different idea of ‘worldmaking’ in comparison to their western counterparts. How can the West approach Asia while respecting the latter’s worldviews?

China and India have broadly convergent views on the need to adjust the West dominated international order, its institutions and its various norms and rules of global governance so that they are more aligned to their respective interests. But the West has been resistant to such change. Take, for example, the voting rights in the World Bank and IMF, which certainly do not reflect the relative economic importance of major emerging economies. The two countries also have a shared interest in shaping emerging global regimes in areas such as Climate Change, Cyber Security, and the safety of space-based assets. One reason why India was ready to join the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) or the BRICS Development Bank was because the West was not ready to acknowledge the interests of the large emerging economies. In approaching Asia, the West will have to acknowledge that the centre of gravity of the global economy has moved to Asia and a stable global order must find ways to accommodate the interests of other major actors, several of whom are in Asia.

The Galwan valley incident was a critical inflection point in the bilateral relations of both the Asian giants, China and India. How far do you think the South Asian region has been impacted post-Galwan?

Galwan was an inflection point in India-China relations because it was the first time since 1976 that there was a violent encounter in which several lives were lost on both sides. But this incident was preceded by aggressive stand-off between Indian and Chinese patrols in the Pangong Tso area. A similar and extended stand-off had also taken place in 2017 at Doklam, which is at the India-China-Bhutan trijunction area. So Galwan was the culmination of more tense confrontations at various points on the border. India-China relations have inevitably worsened as a result although the two sides are engaged with each other in negotiations aimed at resolving outstanding issues. The state of India-China relations does have an impact on India’s and China’s relations with South Asian countries. China’s alliance with Pakistan has become stronger and the prospect of greater Chinese intrusion into the rest of India’s periphery has become more salient. China has been trying to form a regional forum that would include Pakistan, Afghanistan, Nepal, and Bangladesh and potentially Bhutan, focusing on regional connectivity and economic cooperation. There could also be a revival of China’s bid to join as a full member, the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) which has been unable to convene because of Indian opposition, since Pakistan would be the host, observing the principle of rotation. These would be negative developments for India.

In your recent book, How China Sees India and the World, you touch upon the idea of the Middle Kingdom. What is the extent to which China defines its centrality vis-a-vis others? Is it limited to the Asian imagination or does it go way beyond that?

Throughout its long history, China has seen itself as a centre of advanced culture and civilization surrounded by concentric circles of less cultured and inferior countries. It was also under constant assault by the aggressive and hostile tribes on its land frontiers to the north and the west. It is this historical experience which has given rise to the Middle Kingdom complex and a hierarchical conception of power. China aspires to create a regional order in Asia which it would dominate with lesser powers acknowledging its ascendant status and defer to it. It is through the dominance of Asia that the way would be open for a China dominated global order.

There is a pervasive perception problem and mistrust as to how China and India deal with each other. What is your broad take as to how both countries can reconcile, and resolve their mutual differences stemming from the border issue and move towards a more comprehensive partnership?

India and China know very little about each other and harbour stereotypical perceptions of each other. It is only through greater engagement and familiarity with one another, unmediated through third countries, that it may be possible to foster better understanding and establish a more stable relationship. I believe that India-China relations are, by their very nature, adversarial so the objective of our China policy should be to manage the adversarial relationship in a manner that it does not descend into armed conflict. As pointed out earlier, there are areas of convergent interest between the two sides, the pursuit of which may create an environment in which it may be easier to deal with difficult issues, including the border dispute.

What is the most important advice you could give to young scholars of International Relations?

Keep an open mind, treat theories of international relations only as analytical guides to be tested against practical experience. We are living through an age of momentous changes where the geopolitical landscape is changing but the contours of what may eventually emerge are not very clear. It is an exciting time for students of international relations to explore these changes and seek to discern patterns in them. Good luck!