The dominant measure of a country’s development in world politics is the annual total value of production expressed as Gross Domestic Product (GDP), which originates from 20th Century American capitalist thinking (Lepenies, 2016). The mere focus on economic growth is not only problematic in terms of external environmental costs (e.g., He et al., 2019), but it also ignores alternative understandings of development such as buen vivir in Ecuador and Gross National Happiness (GNH) in Bhutan that go beyond materialism (Braun, 2009; Van Norren, 2020). In GNH terminology, development stands for balancing equitable economic growth, cultural preservation, environmental protection, and good governance (Ura et al., 2012, p. 6). This idea travelled beyond its region of origin because of Bhutan’s successful norm entrepreneurship within the United Nations (UN), which led to the UN Resolution 65/309 (2011) to take a holistic approach to development and the UN Resolution 66/281 (2012) that declares 20 March as the World’s Happiness Day (Theys & Rietig, 2020, p. 1603). Despite these resolutions, a decade later, and the awareness that a better measure of development is necessary, GDP remains the standard measure and model for development in world politics (Benjamin et al., 2021). It seems that the West continues to dictate the political language for development despite existing alternatives, hence, this epistemic injustice perpetuates colonial social patterns and reinforces global inequality (Rivas, 2018, p. 166).[1] It is therefore important to understand how development measured by GDP instead of GNH is normalised.

The existing literature about GNH as an alternative to GDP either concentrates on the effectiveness to measure development (Brooks, 2013; Schmidt, 2017; Chuki, 2019), or Bhutan’s GNH-based identity (Avieson & Tschering, 2017; Kaul, 2021; Long, 2021). While these studies offer interesting insights on sustainable development and identity politics, they overlook the power of discourse in constituting the norm and ‘normal’ regarding the measure of development. Travel narratives do not only tell a story about ‘another place’ but they are also used in postcolonial analyses that uncover Eurocentrism, Westerncentrism, Orientalism and other systems of oppression that enable the dominance of the Global North in world politics (e.g., Ahmad, 2011; Roddan, 2016). Focussing on Orientalism (Said, 1978), this paper aims to answer the research question: How do Western travel narratives about Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness model normalise Gross Domestic Product as the measure of development?

This paper takes a Humanities-based approach to IR by drawing from Cultural Studies to analyse the narratives of Western travel vlogs about Bhutan’s GNH model, focussing on the introduction, the plot (i.e., the storyline), and the characters (Ryan, 2017). Discourse expressed through popular culture products is a form of micropolitics that shapes our everyday common sense and understanding of issues in world politics (Duncombe & Bleiker, 2015, p. 37). This paper therefore aims to contribute to a sub-field of IR pioneered by Caso and Hamilton (2015), namely Popular Culture and World Politics (PCWP). While video games, films, music, and the arts are well-analysed (Caso & Hamilton, 2015, p. iii), travel vlogs are a hitherto overlooked dimension of PCWP. Using critical discourse analysis, this paper reveals that Western travel vlogs orientalise Bhutan, exoticize GNH, and normalise GDP, thereby contributing to the perpetuation of GDP’s dominance as the normal measure of development.

This research paper is structured as follows. The first section reviews the existing explanations for GDP’s dominance over GNH in world politics, noting that this literature offers an important but still limited account of the ideational realm and the normalisation of GDP. The second section sets out the theoretical framework and methods. The third section analyses travel vlogs by Anglophone YouTubers to render a better understanding of GNH’s subordinated position vis-à-vis GDP. Arriving at the conclusion, the last section answers the research question and suggests ideas for future research.

State of the Art

In the Sustainability Studies and Development Economics literature, the debate about GNH and GDP can be placed on a continuum. On the one hand, some scholars claim that GNH is a better social indicator than GDP because sustainable development should include the socio-cultural needs of society (Brooks, 2013; Schroeder & Schroeder, 2014; Yangka et al., 2018; van Norren, 2020). On the other hand, there is criticism of Bhutan’s implementation of its GNH development model for not sufficiently tackling unemployment and poverty (Santos, 2013; Schmidt, 2017), perpetuating gender inequality (Verma & Ura, 2018), and neglecting LGBT rights (Chuki, 2019). Forming a middle position, others advocate for GNH and GDP as complementary development strategies (Lepely, 2017; Masaki, 2021). While one can claim that GNH as a social indicator is subordinate to GDP based on the aforementioned shortcomings, this argument disregards the limitations of GDP concerning negative external costs and the inability to measure psychological well-being as expressed in the literature (see Van den Bergh, 2009; Fioramonti, 2013). It becomes clear that these material explanations do not only lack a scholarly consensus, but they are also insufficient to explain GDP’s dominance in development discourse in world politics. This demands a focus on the ideational instead of the material realm, considering GNH as an idea instead of implemented model for development.

We here turn to the existing IR literature scholarship on GNH, which revolves around understanding GNH as a unique trademark in Bhutan’s national identity that generates power and influence. Realist studies claim that the status derived from the GNH development model is quintessential to Bhutan’s state survival as a materially weak power awkwardly located between the two Great Powers China and India (Avieson & Tschering, 2017; Long, 2021). Meanwhile, Social Constructivists maintain that Bhutan’s GNH-based national identity unlocks diplomatic influence in global governance (Monaco, 2016; Kaul, 2021, p. 24; Theys & Rietig, 2020). While these studies offer valuable insights into how Bhutan portrays itself on the international stage, it pays little attention to how Bhutan’s GNH development model is perceived. In Tourism Studies, only Teoh (2012) analyses Australian perceptions of Bhutan’s GNH tourism policy but fails to expose how these are inextricably bound up with the legacies of colonialism. This research paper aims to contribute to the academic debate with a post-colonial analysis of online Western travel narratives about Bhutan’s GNH model, which is discussed in the next section.

Methodology

Postcolonialism in International Relations (IR) is a theoretical lens that reveals how colonial social structures still shape the contemporary social world. Building further on Said (1978), one of its key tenets is attending to the politics of representation that is often linked to Orientalism and exoticism (Biswas, 2010, pp. 222-223). Orientalism is the practice of defining the East through a Western lens that engenders and perpetuates Western dominance through othering practices. It discursively pictures the East as exotic, spiritual, undeveloped, and primitive, in contrast to the ‘better’ enlightened, rational, and developed West, establishing the identity of the Western Self by orientalising the Eastern Other (Said, 2003, pp. 1-8). Therefore, Postcolonial Theory in IR is most appropriate to understand the unequal discursive representation of GDP over GNH, in which the West has flirted with the idea of GNH but sticks to GDP. To reiterate a clarification, the West/non-West conceptualisation is debatable (Bilgin, 2008, pp. 7-8). Here, ‘the West’ refers to geographical regions with Euro-American cultures, namely North America, Western Europe, and Australia, for analytical purposes in the limited scope of this paper.

Travel narratives have historically been an important tool in the sense-making processes about places other than home, making them particularly relevant for post-colonial analyses (Ahmad, 2011; Roddan, 2016; Said, 1978). In the age of social media, it is important to consider non-traditional material such as travel vlogs to understand how the collective imagery of Bhutan is shaped in the West. Vlogs are the video format of blogs and show the audio-visual documentation of the narrator’s first-person experience of the travel destination (Trinh & Nguyen, 2019, p. 15). Basarangil (2020) shows that vlogs have a higher social impact than blogs based on their circulation rate and views, which is the reason that this paper concentrates on travel vlogs instead of blogs as the primary data.

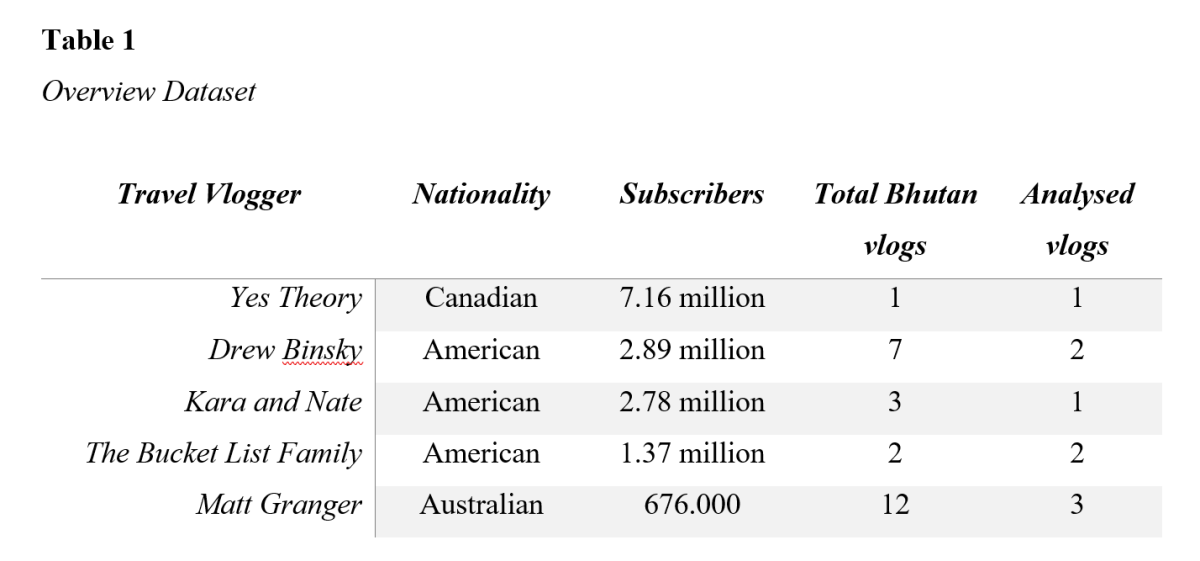

Five YouTube accounts—Yes Theory, Drew Binsky, Kara and Nate, Matt Granger, and the Bucket List Family—were selected based on the following criteria. Firstly, the large number of subscribers and the active engagement with their online content in terms of views, comments and likes signal that their travel vlogs have a large audience. Moreover, these popular YouTubers have more discursive authority and credibility than amateur vloggers, which adds to the social impact of their discourse. Secondly, these YouTubers are professional travel vloggers from the West, which fits the research focus on Western perspectives. Except for Yes Theory, these YouTubers have multiple travel vlogs about Bhutan. However, only the vlogs that touch upon Bhutan’s GNH model and the happiness of Bhutanese people were selected, which resulted in analysing nine vlogs in total (see Table 1).

The method of analysis is critical discourse analysis, which uncovers how discourse reproduces unequal power structures and perpetuates social patterns of domination and control (Catalano & Waugh, 2020, pp. 1-3). This is the most appropriate method for two reasons. Firstly, this paper analyses both linguistic and non-linguistic discourse, namely speech and visual image, in online audio-visual material. Secondly, the postcolonial lens focuses on revealing colonial power asymmetries, and critical discourse analysis is the suitable method to achieve this. Although narratives, or stories, are made up of several elements (Ryan, 2017), this paper concentrates on the introduction, the plot and the characters are the fundamental building blocks of a travel narrative about a place other than home. It is to this analytical focus that the next section turns.

Western Travel Narratives About Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness

Introduction: titles and thumbnails

Before playing a YouTube video, the audience can see the title and the thumbnail, which is the still image that gives a preview of the video. Setting the tone for the travel narrative, the vlog titles of Yes Theory, Drew Binsky, and Matt Granger explicitly identify Bhutan as the land of happiness. For example, “Travelling to the Happiest Country in the World!!” (Yes Theory, 2019, December 1), “The World’s Happiest Country?! Gross National Happiness” (Binsky, 2018, July 28), and “Bhutan—The Happiest Place on Earth” (Granger, 2018, January 1). Moreover, their thumbnails only display smiling white travellers and/or happy Bhutanese locals. This is not only an awkward imagery of the white voyage in exotic places with natives of colour, but it also conjures up the image that Bhutan is a place that supposedly makes everyone happy. The combined social effect of both the linguistic construction of the titles and visual images of the thumbnails is that Bhutan as a geographical location is singled out as the unique space of happiness, and thus GNH becomes a uniquely Bhutanese phenomenon. Consequently, such discourse contributes to the imagery of GNH as exceptional in a place far from developed countries where GDP is the standard measure of development. This inherently implies the incompatibility of GNH with GDP. In addition to the emphasis on ‘happiest country’ with yellow letters in Drew’s preview, the temple, the Bhutanese flag with the Thunder Dragon, the smiling monk, and the traditional clothing in these thumbnails all add to the exoticisation of Bhutan.

The other travel vlogs introduce Bhutan as a primitive place in the Rousseauian sense because it is ‘hidden away in the Himalayas’ and untouched by Western modernisation. In Discourse on Inequality (1755), Rousseau advocates for authenticity in a moral sense because the ideal way of life would be a solitary existence in the absence of language, material properties or any other external influences. All social constructions are deemed artificial and inauthentic (Doorman, 2012, pp. 27-33). Rousseau’s plea for authenticity does not concern a return to the primitive homo sapiens’ past, instead, it is a moral compass for people to live a simple life without alienation from their personal nature due to culture. This moral compass still lives in today’s Western collective consciousness (ibid., pp. 67-72). The problem is that the Eurocentric lens on primitivity fetishizes Bhutan and contributes to the binary distinction between the West as civilized, modern, and globalising vis-à-vis the non-West as unmodern, primitive, and solitary. This distinction is characteristic of Orientalist discourse (Said, 2003, p. 8). It therefore Others the birthplace of the GNH model as unmodern and primitive, and implicitly defines the GDP model of the Self as originating from a modern and civilised place. It can be concluded that the first impression of these videos is either the image of Bhutan as the land of happiness or as an exoticised primitive Himalayan country – both contributing to the idea of GNH as abnormal and GDP as normal.

The plot

All plots begin with the same event, namely arriving at Bhutan’s national airport where the vloggers get picked up by their smiling tour guide. The first contact with Bhutanese locals is already in a happy setting. This is no surprise because Bhutan’s restrictive tourism policy does not permit exploring the country without one, which is based on the GNH pillars to preserve the traditional culture and protect the environment (Ura et al., 2012, p. 6) After that, the plots can be organised into two threads: a) experiencing ‘authentic Bhutan’ through its happy citizens, and b) finding out the meaning of GNH.

The first plot can be found in the vlogs of Kara and Nate, Matt Granger, and the Bucket List Family (TBFL). They all claim to experience ‘authentic Bhutan’ during their travel tour, in which they visit a Buddhist monastery and local shops, try out local food, and dance with locals. Kara & Nate and Matt Granger even give up their modern hotel to stay with a local family in a rural village for one night. The climax in these plots is the inner revelation that a simple life governed along the principles of GNH is better than modern life in the West, which is experienced when the vloggers attempt to adopt the Bhutanese rural lifestyle. After observing the village’s farmers working on the land, for example, Kara states that: “Seeing what the people do for work. Every step of the way of making rice. It is clear that people are very happy and hardworking here” (Kara and Nate, 2019, December 31; 08:03-08:12). Meanwhile, TBFL repeatedly emphasises the preservation of traditional culture, one of the GNH pillars, as the reason for Bhutanese happiness when interacting with local monks. The exoticization is evident when TBFL mother states that:

It felt like an Asian fairy tale. I kid you not. I kept waiting for like the real Bhutan to come out and for everybody to start dressing in regular clothes and for all the normal-looking buildings to come out, but no.

(TBLF, 2018, October 28, 16:36-17:01; emphasis added)

The italicised words reproduce the normalisation of Western-style fashion and architecture as ‘regular’ and ‘normal’ in contrast to Bhutan’s traditional clothing and buildings. The expression ‘Asian fairy tale’ fetishizes the image of Bhutan as utopian and unreal. In sum, the first plot constructs the idea that the primitive and traditional cultural lifestyle of the Bhutanese families is an explanatory factor for their extraordinary happiness.

In the second plot, the main character explores the meaning of GNH in Bhutan by talking to locals, which applies to the vlogs of Drew Binsky and Yes Theory. After both vloggers briefly explain the key tenets of GNH, they interview and interact with Bhutanese locals to capture their conceptualisation of GNH. However, they frame all questions about GNH as a uniquely Bhutanese and better alternative to GDP. For example, Thomas of Yes Theory interviews Bhutan’s ex-Prime Minister Tshering Tobgay during which both state that the psychological struggles of people in the West are caused by modern technologies and social media, unlike Bhutan because of GNH principles (Yes Theory, 2019, December 1, 08:12-08:21).

Moreover, the climax in the plots of the travel vlogs by Drew Binsky and Yes Theory pertains to the idea of experiencing happiness, euphoria, and joy in the quote-on-quote country of happiness fostered by GNH. The climax in Drew’s plot is his personal evidence for the success of GNH, which is clear when he excitedly says: “taking a little walk here in the kid’s parks of Paro, and everybody is happy! It is amazing!” (Binsky, 2018, July 29, 00:40-00:44). While the climax of Yes Theory’s plot similarly centres on experiencing happiness in Bhutan, it comes in a different form. After interviewing Tobgay, Thomas hikes up the mountain of the Tiger’s Nest Monastery, which builds up to a spiritual awakening for him as the music becomes increasingly upbeat. At the top, Thomas cries:

We just got out of the Tiger’s Nest and I just had one of the most spiritual moments that I have ever experienced […] there is just something about this place that just leaves me so uncontrollably emotional […] I feel extremely grateful right now to experience this moment.

(Yes Theory, 2019, December 1, 12:29; 13:04-13:26)

Thomas’ spiritual moment is linked to the scenery of the vlog, namely the Buddhist monastery in the mountains that is preserved through Bhutan’s GNH policy. The speech, excited facial expression, music, and emotions of Drew and Thomas affect the viewer with feeling their excitement. Peralta argues that the viewer identifies the destination as a place of happiness when travel vloggers record their enjoyment of a place (2019, p. 11). In this way, they orientalise Bhutan as the land of happiness that was made possible by the country’s GNH model.

Thomas ends his vlog with: “What do you think that the world can learn from Bhutan’s happiness; I guess making happiness the priority!” (Yes Theory, 2019, December 1, 08:12-08:21). Similarly, Drew concludes his exploration of GNH by stating: “if you take away one message from my videos of Bhutan, please let it be that life is perfect in this country” (Binsky, 2018, July 29, 02:33-02:37). Presenting Bhutan’s GNH model as the formula to a perfectly happy life is problematic as it covers up the issue of alcoholism and structural poverty of Bhutan’s citizens (Ongmo & Parikh, 2019, September 26). Moreover, the emphasis on what the West should learn from the mystical Other, Bhutan, again exoticizes GNH and implicitly accepts GDP as the standard measure of development.

The characters

Every narrative has different characters, of which the main character plays the starring role. Here, the travel vloggers are both the main characters and the narrators of the story. The point of view is the first-person as the vloggers directly speak into the camera to narrate their story about Bhutan and the GNH model. This results in a problem of representation because non-Bhutanese vloggers who have relatively more power in terms of wealth distribution, cultural domination and representation in world politics tell the story of the Bhutanese people: their day-to-day life (Biswas, 2010, pp. 222-223). Thomas even begins the interview with ex-prime minister Tobgay by asking what Gross Happiness Income means, to which Tobgay awkwardly corrects him that it is GNH (Yes Theory, 2019, December 1, 05:38-05:40). This ignorance leads to misrepresentation, and it perpetuates the colonial social pattern of the Self that observes and reports about the exotic Other.

An interesting aspect of character representation in vlogs is the use of music, and its affective effect (see Davies & Franklin, 2015). Whenever the people or landscape of Bhutan are on screen, Oriental music is in the background with a harp, a flute, a bamboo whistle, and sometimes even meditative chanting. Meanwhile, modern music made with computer technology such as electronic dance music and lounge music is used when the vloggers are in action on screen. This contrast reinforces the idea that Bhutan is undeveloped, primitive, and exotic, in contrast to the modern and technology-infused West. Implicitly, GNH then belongs to a backward country that is too exotic for the West.

Except for ex-prime minister Tobgay’s supporting role, the Bhutanese locals do not play a role other than exotic objects. When Bhutanese locals say something in the vlogs, they seem to be very aware of the presence of a Western tourist audience. In the vlogs of Kara and Nate, Yes Theory, and Drew Binsky, these figurants give short statements about GNH and their happy lifestyle in English, but it seems very staged and bumpy as they try to remember the rights sentences. After Drew states that everyone watching Drew’s vlog probably knows what GDP means, he lets his Bhutanese tour guides shout one-liners in choir with little breaks between each word “Gross National Happiness” (Binsky, 2018, July 29, 00:06-00:20). This somewhat child-like way of speaking constructs the idea of the Bhutanese as undeveloped if not uncivilised as they do not properly speak English in comparison to the English-speaking vloggers.

The Bhutanese figurants are portrayed as people who are always happy in their primitive state of being through linguistic expressions and visual images. For example, Drew expresses that: “Bhutan is consistently ranked as the happiest country in Asia, and it is obvious when you see their smiles” (Binsky, 2018, July 29, 01:55-02:00). Regarding visual images of Bhutanese citizens, the vlogs only show locals who are smiling, laughing, and experiencing joy. Moreover, all vlogs show a problematic pattern regarding the spatial organisation of the visual images in terms of the position offered to the viewer. Shots of the locals are often taken from an aerial view or from above with either a selfie stick or a drone. This framing leads to an unequal power position in which the viewer stands above the objects to be observed in the visual image (Rose, 2016, pp. 71-72). When Bhutanese people are filmed in close-ups, this is always montaged into a slow-motion moment in which the Western viewer can observe the exotic Other. In that sense, life in Bhutan slows down to enable the colonial observation of foreigners and a foreign landscape. Meanwhile, all actions and events that involve the white vloggers themselves are recorded at face height and without slow motions.

The overall social effect is that Bhutanese citizens become a tourist attraction with whom the travellers can interact and experience the happiness of the authentic Bhutanese lifestyle. They are exoticized as the citizens of the ‘land of happiness’ who are sheltered from the pain and hardship that is experienced in industrial capitalist countries. This utopian dream supposedly has manifested through Bhutan’s GNH-driven policy, hence GNH is exoticised. This very notion of GNH as exceptional inherently implies that GDP is normal in the vloggers’ discourse about GNH vis-à-vis GDP.

Conclusion

Using a postcolonial lens and critical discourse analysis, this paper has uncovered how Western travel narratives in YouTube vlogs exoticize GNH and normalise GDP. The findings reveal that the introduction, plot, and characters contribute to a romanticised image of GNH as the exceptional formula for Bhutan as the land of happiness that exists in primitive solitude—hidden away in the Himalayas—in the Rousseauian sense. These storylines centre on how the vlogger protagonists experience GNH and happiness in ‘authentic Bhutan’ either via interviews or interactions with Bhutanese locals, making the latter exotic objects in the process. The Oriental music, camera angles, thumbnails, temple and dragon images, and ignorant speech acts in the travel vlogs about Bhutan’s GNH model orientalise, and therefore other, this measure of development. It creates a problematic Western desire for the primitivity of the exotic Other that is exceptional in comparison with the modern everyday Western Self. It can therefore be concluded that the social effect of these narratives is constructing the collective imagery of GNH as an exotic unicum and the GDP development paradigm as the norm.

This paper has taken a Cultural Studies approach to IR, which enriches the discipline with an interdisciplinary analysis of popular cultural products and their micropolitics (Katzenstein & Sil, 2008). Its value-added resides in using travel vlogs as a hitherto unexplored dimension in IR’s subdiscipline of PCWP (Caso & Hamilton, 2015). It takes PCWP research in IR to the online world and relates it to the offline world—two inextricably linked dimensions of our everyday sense-making in contemporary international relations. Indian travel vlogs about Bhutan’s GNH model also came to light during the data collection process, but they were excluded from the dataset because this paper focuses on Western perceptions. Further research should use a postcolonial lens akin to Ling (2002) – paying attention to internalised colonial thought in ex-colonies—to examine if and how the above narratives are reproduced or countered in non-Western travel vlogs about Bhutan’s GNH. Another suggestion for future post-colonial IR studies on travel vlogs, which was beyond the scope of this paper, is an in-depth discourse analysis of the covered colonial racism and exoticism toward Asian inhabitants that enables Hypermasculine Eurocentric Whiteness (see Prianti, 2019; Ling, 2019)—a system of oppression that still colonises world politics.

Notes

[1] While the binary distinction between the West and the non-West is contentious (Bilgin, 2008, pp. 7-8), ‘the West’ in this paper refers to regions with Euro-American cultures, namely North America, Western Europe, and Australia. It is used as an analytical term referring to a geographical space, not a culture or any way that contributes to Westerncentrism.

Bibliography

Ahmad, R. (2011). Orientalist imaginaries of travels in Kashmir: Western representations of the place and people. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 9(3), 167-182.

Avieson, B., & Tshering, K. (2017). Seduced by Bhutan’s philosophy of happiness. In N. Chitty, L. Ji, G. Rawnsley & C. Hayden (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Soft Power (pp. 389-400). Routledge.

Basarangil, I. (2020). Bloggers out, vloggers in: A study on the investigation of effects on travel perceptions. In V. Krystev, M. S. Dinu, R. Efe, & E. Atasoy (Eds.), Advances in Social Science Research (pp. 451-467). St. Kliment Ohridski University Press Sophia.

Benjamin, D., Cooper, K., Heffetz, O., & Kimball, M. (2021). Measuring the essence of the good life: The search continues for a better gauge of prosperity than GDP alone. International Monetary Fund, Finance & Development. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2021/12/Measuring-Essence-Good-Life-Benjamin-Cooper-Heffetz-Kimball

Bilgin, P. (2008). Thinking past ‘Western’ IR?. Third World Quarterly, 29(1), 5-23.

Biswas, S. (2010). Postcolonialism. In T. Dunne, M. Kurki & S. Smith (Eds.), International Relations Theory. Discipline and Diversity (pp. 220-236). Oxford University Press.

Braun, A. A. (2009). Gross National Happiness in Bhutan: A living example of an alternative approach to progress. Social Impact Research Experience Journal, 33-38.

Brooks, J. S. (2013). Avoiding the limits to growth: Gross National Happiness in Bhutan as a model for sustainable development. Sustainability, 5(9), 3640-3664.

Chuki, S. (2019). Being LGBT: Their status and rights in Bhutan. Australian Journal of Asian Law, 20(1), 217-134.

Davies, M., & Franklin, M. I. (2015). What does (the study of) world politics sounds like?. In F. Caso & C. Hamilton (Eds.), Popular Culture and World Politics: Theories, Methods and Pedagogies (pp. 120-147). E-International Relations Publishing.

Doorman, M. (2012). Rousseau en Ik [Rousseau and I]. Uitgeverij Bert Bakker.

Drew Binsky. (2018, July 29). The World’s Happiest Country?! (GROSS NATIONAL HAPPINESS) . YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YsQPqwzg8is

Duncombe, C., & Bleiker, R. (2015). Popular culture and political identity. In F. Caso & C. Hamilton (Eds.), Popular Culture and World Politics: Theories, Methods and Pedagogies (pp. 35-44). E-International Relations Publishing.

Fioramonti, D. L. (2013). Gross Domestic Problem: The politics behind the world’s most powerful number. Zed Books Ltd.

Granger, M. (2018, January 1). Bhutan – The Happiest Place on Earth . YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O9JFkuWNHCU&t=5s

He, F. S., Guan Gan, G. G., Al-Mulali, U., & Adebola, S. S. (2019). The influences of economic indicators on environmental pollution in Malaysia. International Journal of Energy Economics, 9(2), 123-131. https://doi.org/10.32479/ijeep.7489

Kara and Nate. (2019, December 31). WE LIVED WITH A LOCAL FAMILY IN BHUTAN (life in a rural village) . YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jPe0V4TXdsg&t=495s

Katzenstein, P., & Sil, R. (2008). Eclectic theorizing in the study and practice of international relations. In Reus-Smit, C., & Snidal, D. (Eds.,) The Oxford Handbook of International Relations (pp. 109-130). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199219322.003.0006

Kaul, N. (2021). Beyond India and China: Bhutan as a small state in international relations. International Relations of the Asia-Pacific, 00, 1-41. https://doi.org/10.1093/irap/lcab010

Lepeley, M. T. (2017). Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness: An approach to human centred sustainable development. South Asian Journal of Human Resources Management, 4(2), 174-184.

Lepenies, P. (2016). The Power of a Single Number: A political history of GDP. Columbia University Press.

Ling, L. H. M. (2002). Postcolonial International Relations: Conquest and desire between Asia and the West. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Ling, L. H. M. (2019). Köanizing IR: Flipping the logic of epistemic violence. In K. Shimizu (Ed.), Critical International Relations in East Asia: Relationality, Subjectivity, and Pragmatism (pp. 64–85). London: Routledge.

Long, W. J. (2021). Modern Buthan Buddhist Statecraft. In W. J. Long (Ed.), A Buddhist Approach to International Relations: Radical Interdependence (pp. 71-86). Palgrave Macmillan.

Masaki, K. (2021). Exploring the ‘partial connections’ between growth and degrowth debates: Bhutan’s policy of Gross National Happiness. Journal of Interdisciplinary Economics, 02601079211032103.

Monaco, E. (2016). Notes on Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness and its measurement. Journal of Management and Development Studies, 27, 1-15.

Ongmo, S., & Parikh, T. (2019, September 26). Addicted in Bhutan: The country’s substance abuse is undermining its focus on gross national happiness. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/09/26/addicted-in-bhutan/

Peralta, R. L. (2019). How vlogging promotes a destination image: A narrative analysis of popular travel vlogs about the Philippines. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 15(4), 244-256.

Prianti, D. D. (2019). The identity politics of masculinity as a colonial legacy. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 40(6), 700-719.

Rivas, A. (2018). The everyday practices of development. In O. Rutazibwa & R. Shilliam (Eds.), Routledge Handbook Postcolonial Politics (pp. 166-178). Routledge.

Roddan, H. (2016). ‘Orientalism is a partisan book’: Applying Edward Said’s insights to early modern travel writing. History Compass, 14(4), 168-188.

Rose, G. (2016). Visual Methodologies: An introduction to researching with visual materials. Sage.

Rousseau, J. (1755). Discours sur l’origine et les fondements de l’inégalité parmi les hommes [The Discourse on the Origin and the Basis of Inequality Among Men]. N.P.

Ryan, M. L. (2017). Narrative. In I. Szeman, S. Blacker & J. Sully (Eds.), A Companion to Critical and Cultural Theory (pp. 517-530). John Wiley & Sons Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118472262.ch33

Said, E. W. (1978). Orientalism: Western Concepts of the Orient. Pantheon.

Said, E. W. (2003). Introduction. In E. Said (Ed.), Orientalism (pp. 1-28). Penguin.

Santos, M. E. (2013). Tracking poverty reduction in Bhutan: Income deprivation alongside deprivation in other sources of happiness. Social Indicators Research, 112(2), 259-290.

Schmidt, J. D. (2017). Development Challenges in Bhutan. Springer, Cham.

Schroeder, R., & Schroeder, K. (2014). Happy environments: Bhutan, interdependence and the West. Sustainability, 6(6), 3521-3533.

Teoh, S. (2012). The ethics platform in tourism research: A western Australian perspective of Bhutan’s GNH tourism model. Journal of Bhutan studies, 27, 34-66.

Theys, S., & Rietig, K. (2020). The influence of small states: How Bhutan succeeds in influencing global sustainability governance. International Affairs, 96(6), 1603-1622.

The Bucket List Family (TBLF). (2018, October 28). HAVE YOU HEARD OF BHUTAN??!/ The Bucket List Family . YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vOJ41vNasBs&t=1038s

Trinh, V. D., & Nguyen, D. Y. L. (2019). How to change perceived destination image through vlogging on Youtube. In [no editors], SSRN: the Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Management Science ‘DIGITAL DISRUPTION ERA: Challenges and Opportunities for Business Management (pp. 1-20). http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3426968

Ura, K., Alkire, S., Zangmo, T., & Wangdi, K. (2012). An Extensive Analysis of GNH Index. The Centre for Bhutan Studies.

Van den Bergh, J. C. (2009). The GDP Paradox. Journal of Economic Psychology, 30(2), 117-135.

Van Norren, D. E. (2020). The Sustainable Development Goals viewed through Gross National Happiness, Ubuntu, and Buen Vivir. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 20(3), 431-458.

Verma, R., & Ura, K. (2018). Gender differences in Gross National Happiness in Bhutan: Abridged analysis of the GNH surveys. In D. K. Ura & D. Penjore (Eds.), GNH: From Philosophy to Praxis (196-247). Centre for Bhutan Studies & GNH.

Yangka, D., Newman, P., Rauland, V., & Devereux, P. (2018). Sustainability in an emerging nation: The Bhutan case study. Sustainability, 10(5), 1622-1638. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10051622

Yes Theory. (2019, December 1). Travelling to the Happiest Country in the World!! . YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qmi-Xwq-MEc&t=226s

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Do Postcolonial Approaches Explain World Politics Better than Other IR Theories?

- How Fear Shapes World Politics

- Do Colonialism and Slavery Belong to the Past? The Racial Politics of COVID-19

- Do Human Rights Protect or Threaten Security?

- The BRICS Bloc: A Pound-for-Pound Challenger to Western Dominance?

- To Reform the World or to Close the System? International Law and World-making