Flight of the Drone: Israeli Defense Forces’s Hermes 450

The latest conflict between the Israeli Defence Force (IDF) and the Palestinians in Gaza during 2008-2009 was at the heart of military controversy due to the extensive use of drones, or in military jargon- ‘unmanned combat aerial vehicles’ (UCAVs) (Ophir et al, 2009). The Israeli’s Elbit Hermes 450 UCAV binds together complex Intelligence, Surveillance, Reconnaissance (ISR) and hi-tech weapons systems affixed to an unpiloted light-aircraft providing in-depth detail of the battlespace (Gregory, 2011a; Elbit Systems, 2012). However, the UCAV is much more than an object of military life targeting individuals, groups and landmarks to accomplish missions. It is ravelled in layers of complex political powers challenging physical terrain of geography and political human aspects of spatial military discourse. Thus, this paper critically analyses how the Hermes 450 and UCAVs as objects project political power in territorial conflicts and/or disputes.

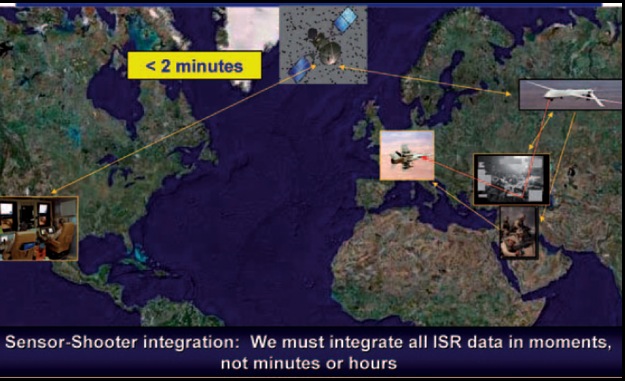

Hermes 450 is part of a pervasive military matrix melting away geographies projecting political power to re-carve the geopolitical landscape. Guiding the UCAVs rely upon series of networks all interlinked through satellite connections ensuring the ‘pilot’ is hundreds of miles from the battlefield but precision and time are not consequently compromised (Bookstaber, 2000) (Plate 1). The real time footage uploaded onto the screens of IDF operators with Facebook style chats ensure instant communication and action which compresses the kill-chain to two simple processes, ‘aim’ and ‘fire’ (Kaplan, 2006) (Plate 2). The high technological functionality of UCAVs challenges physical geographical terrain, borders and boundaries reducing time and space to remould places of war to a globalised battlespace.

Plate 1: Impersonal Warfare - Pilots are based hundreds of miles from their targets

Manufacturers of the Hermes 450, Elbit Systems allegorically project political power over geographies through complex military systems and networks bringing together alliances in two ways. Firstly, research and development processes of UCAVs require the sharing of intelligence and capital between allies to be able to create drones. For example drones “found contained labels from [America’s] Motorola…and MCB Industrie of France (HRW, 2009:12). Secondly, the compression of the kill-chain requires a communicational infrastructure spatially distributed over geography. Therefore, alliances are formed and strengthened over geographies through the manufacturing and operational processes of UCAVs.

Plate 2: Compressing the Kill-Chain - Interconnectedness of key players navigating UCAVs perpetuates a new dimension of time-space compression.

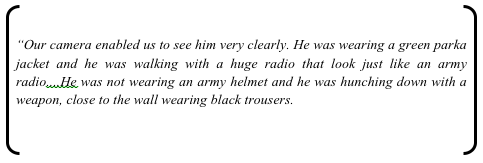

The final strand of critical engagement with UCAVs explores the technicalities of the operational process of ‘targeting’. Targeting the enemy through hi-resolution, and infra-red cameras built onto the body of the UCAV requires the operator to identify between ‘target’ and ‘civilian’. This God-like practice of identity classification results in the decision-making of life and death (Haraway, 1988). Thus, the ability to choose to create identities but also to destroy them in conjunction with powerful visualities gives UCAVs the ability to alter the future of place. Shaping geographical futures is a powerful political tool of the Hermes 450 greatly benefitting the IDF over the Palestinians in Gaza.

This paper argues that objects not only project political power but also form political powers through time-space compression, political alliances and the formation of futures. Questioning the ethics behind the extensive use of drones by the IDF in Palestinian territories challenges projected political power on and over geography. Therefore, the second part of this essay explores the ethical concerns over the use of UCAVs. This paper argues the ethical process of drone warfare challenges the political power projected by the Hermes 450. The object both forms and performs political power in territorial conflicts and disputes but is continually challenged by members of the public, the media and non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

Re-carving Time-Space Compression

Arguments surrounding the ‘shrinkage of time-space’ are nothing new (see, Allan and Hammet, 1996) but the power of political objects in perpetuating this process is new academic territory. Drones drastically reduce the time and distance that would usually be encountered if conventional forces were used (foot-soldiers, tanks etc.). For example, IDF troops ‘tabbing’ (fast-march with full kit) from Lod Airbase would take 21 hours and 8 minutes to Kiribat Ikhza’a, Gaza Strip whilst the use of a vehicle would shave the time to an hour and a half (GoogleMaps, 2012). Using the Hermes 450 from Lod Airbase travelling at the maximum speed of 176 km/h would take c.40 minutes to reach this target (GoogleMaps, 2012; Elbit Systems, 2012) (Figure 1). Therefore, time taken from target to kill is reduced significantly due to the technological militarization of time-space (Adey, 2011). Both time and distance no longer challenge the science of warfare. Consequently, UCAVs are powerfully reconfiguring the physical geopolitical landscape. UCAVs project political power on the geographical landscape through reducing time and space between the target and the kill.

Figure 1: Mapping Targets - Lod Airbase to Khiribat Ikhza’a

Geographical distance is also transformed through the development of ‘Network Centric Warfare’ whereby physical space is made increasingly redundant due to cyber networks (Clarke and Knake, 2010). Satellites circulating in the Earth’s orbit reconceptualise the way in which space and distance should be imagined in geopolitical literature. The UCAV represents a new dimension to conceptualizations of the spatiality of warfare through the reduction of distance. Derek Gregory (2011b) argues the UCAV causes ‘the death of distance’ as battlespace becomes increasingly globalised and bombing is inevitably borderless (see Slavick, 2007 in Plate 3). The complex surveillance networks and real-time communicational systems strengthen this claim. UCAVs project political power on geographies to rapidly minimise time and space to perform militarised processes in a milieu of instant warfare. Coleman (2005) suggests the process of time-space compression alters conceptions of the militarised ‘frontline’. The frontline is constructed as borderless through rapid re-bordering by the drones thus, creates a battlespace absent from a start or a finish. The configuration of the frontline questions the authority of the state and the notion of sovereignty. The Hermes 450 regularly surveils and strikes in order to project Israeli sovereignty and authority further onto and across the Palestinian landscape through the pushing of the frontline to evolve the border. Hermes 450 strips sovereignty away through militarised political power projections shifting the focus of sovereignty from a de jure right to territory which requires obligation and responsibility (Williams, 2009). The Hermes 450, as well as other UCAVs are representative of a technological revolution that forces geography to obey.

Plate 3: Blurred Bombing - Elin O’Hara Slavick, (2007) presents the consequence of modern warfare

Manufacturing and Operating Alliances

Political power is projected through the formation of alliances in two ways, the manufacturing of drones and the communication between networks interacting with each other move from ‘aim’ to ‘fire’. The Hermes 450 may initially be imagined a product of Israel, after all it is manufactured by an Israeli company, operated by the IDF and was contracted by the Israeli government for $47 million (see, Tozer et al, 2005). However, the focus needs to encompass a wider geographical context to explore the interplay relationships between objects and their formulated networks. Elbit Systems is a transnational defence company with a research and development facility located in Fort Worth, Texas, plus two subsidiaries, one in Texas and the other in Virginia. The company owns 49% of the UK aerospace defence company, Thales and heavily influences the European defence markets (Elbit Systems, 2012; Thales, 2012). These ‘special’ relationships are strategically diplomatic in projecting political power and influence over geographies through the research and manufacturing of the Hermes 450.

The Hermes 450 relies on a complex set of ISR systems, even for the shortest of flights. The attacks in Gaza during December 2008 required intelligence sharing from the British and the use of US satellites to guide the UCAV to a location where ‘grad missiles’ (rocket launcher missiles) were being loaded onto multiple vehicles (Johnson, 2009) (Plate 4). The series of inputs on operations like this strengthen the trust between allied forces through creating and reinstalling military connections across the Network Centric Warfare battlespace.

Plate 4: Combat Zones That See - Powerful ISR technology identified grad missiles being loaded onto a Hamas vehicle

Manufacturing and communicational infrastructures facilitate objects to project political powers over geography. These connections are strategically diplomatic to build and solidify new and existing relationships with states. It can be suggested these interrelationship networks of alliances add new dimensions to globalising the battlefield, contributing to the first strand of this argument of time-space compression (see Bridge, 1997; Harvey, 2005[1990]). Alliances are much more powerful, both politically and militarily in succeeding in the Gaza conflict. American support for the drone attacks located across the Gaza Strip and in the West Bank provides (to some extent) a legitimate justification for the extensive use of UCAVs against the Palestinians. Israeli power is strengthened by the use of UCAVs due to the reinforcement of alliances through manufacturing drones and their operational tasks.

Targeting Geopolitical Futures of Identity

Increasing visualization of the ‘target’ has only been possible through the use of extensive state-of-the-art surveillance and monitoring equipment enabling ‘combat zones that see’ (Graham in McDonald et al, 2010). Surveillance systems have become so powerful through drone warfare that they aid the distinction between civilians and targets but also the prioritisation of targets identified in conflicts. The most intricate details are susceptible to the hawkish-eye of these predators that constantly surveil the Gaza Strip (see Figure 2). Military surveillance forms new dimensions to the military-industrial complex combining powers of the state and private sector to categorize identities making the most obvious distinctions between enemy, ally and civilian (Anderson, 2011). The power entrusted in the UCAV operators allows them to shape futures of geographical identity through pre-emptive war, striking targets before attacks on allied forces occur based on measurements of risk intelligence (Galston et al, 2002). Therefore, drones project political futures for the targets they attack but also those targets that are not attacked.

Figure 2: Powerful Visualities - Intricate details picked up by Hermes 450 during surveillance missions over Gaza.

Classification is a powerful tool in reconstructing and simplifying identities and cultures of people. It removes traditional imaginations of what geographers may consider identity to originally be conceptualised as. Reducing cultures, traditions, religions, norms, family traits to simply a target, ally or civilian removes the values of a person and reconstructs imaginations of identity to categorization of a geographical divide of ‘them’ and ‘us’ (Gregory, 2004). The surveillance nature of drones possesses the political power of refining identities to simple categorizations of targets, allies and civilians and thus, reinstalls geopolitical imaginations of identifying the enemy (Said, 2003[1973]). The process can be thought of as one of re-humanization; stripping identity down to the dry-bones and overlaying new identities of for example, ‘terrorists’ to the rest of the world.

The panoptic shift in military surveillance has led to a more powerful force of a God-like nature determining the futures of identities, the decision-making of killing selected targets. Pre-empting the death of individuals in spaces of potential conflict projects a kind of omnipotent presence to the Hermes 450.The attacks on Hamas terrorist organization transporting ‘grad missiles’ prevented a particular type of future from emerging but also re-humanized the active bodies in this process. The Hermes 450 strikes eliminated a number of futures including Israeli deaths, intensity of conflict, increased drone support from the US, UN resolutions to name but a few (Finkelstein, 2003). The re-creation of identity aids the development of futures emerging through objects projection of power. Therefore, futures are formed through the pre-emptive nature of surveillance and classification of the UCAVs and their retrospective operators. Geographical futures are formed and projected through the use of objects in zones of territorial conflict and dispute to benefit the IDF.

The third strand of this argument interweaves two conceptual fabrics of time-space compression and of satellite geo-positioning contributing to the evolution of the Network Centric Warfare battlespace. Drones have made the imaginations of Revolution in Military Affairs (RMA) theorists a physical reality whereby warfare is controlled and co-ordinated through computerization (see Barnett, 2004). However, categorization and computerization are problematic due to reliance on the subjective and erroneous nature of both man and machine. The modernization of warfare and the extensive use drones has raised ethical questions and issues of legality which challenge and restrict political powers of military objects.

Objecting the Hermes 450: Ethics and “Lawfare”

Targeting and the compression of the kill-chain through the extensive use of the Hermes 450 in the Gaza Strip conflict presents a series of ethical challenges that shall be unpackaged through two case studies. Both case studies have been adapted from a Human Rights Watch (HRW) report condemning the use of IDF drones on Palestinians due to the extent of collateral damage. Critical engagement with the attacks at the UNRWA Asma Elementary School, Gaza City and the strikes at a metal shop in Jabalya question the ethical and legal responsibilities of drone warfare by NGOs, the media and the public. This section does not present a debate of ethical issues of the Hermes 450 but argues such presented debates undermine its uses and allegorical political power in the Gaza Strip. The section also engages with the legalities behind drone warfare. In the past scholars and advocates of the ‘Just War’ theory have argued that military operations can be restricted by international legal structures (see, Johnson, 1981; Reagan, 1996; Ramsey, 2002). However, investigations into the legal approval systems behind IDF drones reveal the law is manipulated and diluted to favour military operations. Finally, this part of the paper concludes political power is challenged through the rise in non-statutory bodies questioning the UCAVs ethical frameworks but the so-called ‘legalities’ of drone warfare overcome such opposition.

On the 5th of January, 2009 at 2200hrs, three ‘civilian’ men were directly targeted by an IDF Hermes 450 that killed all targets. The IDF claimed these men were under ISR observations leading operators to believed the men were about to engage in military activities (UNRWA, 2009). However, HRW believe these attacks to be methods of clearing Palestinians from so-called Israeli territory. Deciphering this story further reveals the IDF knew the GPS coordinates of the school and were fully aware of the evacuation of 400 civilians into the school’s buildings. Nonetheless, the IDF still engaged in active airstrikes because the three men were believed to be “dangerous” (Adelman, 2009:94). Similarly a metal shop in Jabalya was pre-emptively attacked as the men were suspected to be loading weapons onto vehicles belonging to Hamas. In response to the controversy that arose from the strike the IDF published a video online whereby “cylindrical objects” could be seen being loaded onto open trucks (HRW, 2009:18). Nevertheless, according to Human Rights Watch (2009) no secondary explosions occurred after the strikes had been carried out, which would have resulted in the explosion of such military warheads. Therefore, it is speculated after investigation that attacks were on civilians, but whether deliberately or accidentally remains subject of political controversy.

Against the landscape of complex technological systems containing powerful surveillance cameras, the margin of error for the Hermes 450 is relatively small. Journalist investigations by the BBC and CNN found no weaponry or ammunition at the site of the strike raising suspicions of why such an attack was carried out. Strikes by UCAVs are still under the same international standards as any other weapon systems, subject to a chain of military lawyers or popularly known as lawfare (Gregory, 2011b; Hajjar, 2012). Nevertheless, the principle of proportionality has fulfilled a niche in the legal system to justify the killing of civilians in warfare. The principles refer to a legal structure whereby if a target is sited to be actively engaging in military activity whilst civilians are present if the threat is greater in proportion to its environment strikes can be carried out despite results of collateral damage (Blau, 2008). Kremnitzer argues “to the effect that if one strikes at a military target an accompanying strike against civilians will not be illegal…” (in Blau, 2008:04). Thus, the law becomes elastic stretching over a broad and ambiguous set of military practices. Another tactic employed to manipulate the law is to state intentions of arrest previously despite objectives to kill selected targets. For example, the death of Muhammed Ramaha on 13th December 2006 was “in the course of a joint arrest operation…” (in Blau, 2008:05). The reconfiguration of military law is powerful in retrospect to using UCAVs by filtering information through media networks to culminate a justification for targeted killing that originally would have been labelled ‘unethical’ and ‘illegal’. Reconstructing the law adds weight to the political projection of military objects in environments of war and conflict.

The exposure of truths through ethical perspectives presents objections to how politically powerful the Hermes 450 actually is. Alliances are much more complex than first perceived, thus, political power projected through the construction of objects can be restrained by breaking the military-industrial complex. Furthermore, the ethical questioning of targeting challenges the formation of a military utopia of a ‘trigger-happy’ environment from emerging. Constant scrutiny towards the use of the Hermes 450 means the IDF has to justify targets through a system of open-sourcing to the public (Gregory, 2011b). However, as displayed through Blau’s (2008) article the law can be manipulated to favour and strengthen the power of drones. Law is merely a tool that is used to combat ethical questioning from NGOs and justify the death of selected targets. Power of UCAVs is both challenged by ethics but re-projected through the law in the Gaza Strip conflict.

Conclusions: A Shift towards Pre-emptive Warfare

Drones contain certain representations, a process of practices and doings and live a political life but it also objects a particular politics of power. Combining these approaches with the arguments of time-space compression, networked powers, geographical futures and questioning of ethics and legalities presents a critical analysis of how objects project political power in territorial conflicts and disputes. The increasing hybridisations of war multiplies the ambiguity of warfare thus, leaves us with a contradictory conclusion confirming objects in conflicts both form political powers and restrain political powers (Chojnachi, 2006). The manufacturing of pre-emptive war attempts to flex political muscle before other states have a chance to. Thus, drones act out political meanings across the international platform through warfare to result in a zero-sum game tipping the balance of power over to their side. However, some of the power gained is challenged through the questioning of NGOs that keep military objects under a system of ‘checks and balances’. Similarly the United States government has developed drone technologies in locations of Pakistan, Iraq and Afghanistan to project their foreign policy of a Global War on Terror. The US has faced questions of an ethical nature against its borderless bombing strategies (see Gregory, 2011a, 2011b). However, lawfare has been used to engage with these challenges to power and reassert government justifications in targeted killing. Thus, targeted killing through UCAVs has a domino effect as the IDF sets a precedent for using such military tactics in engaging with the enemy perpetuating the evolution of a technological warfare paradigm.

The IDF presents a new shift of imperialism through the militarization of Palestinian territory using drones to exert particular political agendas. Installing fear is a geopolitical weapon that opens debates surrounding geographies of emotions that could offer an alternative avenue of research to analyse how objects project political power through the manipulation of the psyche. Nevertheless, this paper has critically engaged with the politicisation of the Hermes 450 to evaluate how political power is projected during warfare. Objects are a symbolism of geopolitical power containing forces that alter geographies of terrains, borders, networks and communications, identity and futures (Gregory, 2011a; McDonald et al, 2010). Objects reduce place and space to alien spaces through folding distance into differences spatially inverting geographical features (Gregory, 2004). Objects project powers to politically simplify geography to the rest of the world conscious to portray the division of them and us in a situation of conflict and dispute.

Bibliography

Adelman, H. (2009) Research On The Ethics Of War In The Context Of Violence In Gaza, Springer Science And Business Media B.V., 7(1), 93-113.

Adey, P. (2011) Introduction: Air Target: Distance, Reach And The Politics of Verticality, Theory, Culture and Society, 28(7-8), 173-187.

Alberts, D.S. Gartska, J.J. And Stein, F.P. (1999) Network Centric Warfare: The Face Of Battle In The 21st Century, National Defense University Press, Washington D.C.

Anderson, B. (2011) Facing the Future Enemy: US Counterinsurgency Doctrine And The Pre-Insurgent, Theory, Culture and Society, 28(7-8), 216-240.

Blau, U. (2008) License To Kill: A Haaretz Magazine Investigation Reveals Operational Discussions In Which The Fate Of Wanted Men And Innocent People Was Decided, Haaretz Online, http://www.haaretz.com/license-to-kill-1.258378 [Accessed, 06/02/2012].

Bookstaber, D. (2000) Unmanned Combat Aerial Vehicles: What Men Do In Aircraft and Why Machines Can Do It Better, Defense Technical Information Center (DTIC), Virginia.

Bridge, G. (1997) Mapping The Terrain Of Time-Space Compression Power Networks In Everday Life, Environment and Planning D, 15(5), 611-626.

Chojnacki, S. (2006) Anything New Or More Of The Same? Wars And Military Interventions In The International System, 1946-2003, Global Security, 20(1), 25-46.

Clarke, R. And Knake, R. (2010) Cyber War: The Next Threat To National Security And What To Do About It, HarperCollins, New York, 69-103.

Crampton, J. (2001) Maps as Social Constructions: Power, Communication and Visualization, Progression in Human Geography, 25(2), 235-252.

Elbit Systems. (2012) Hermes 450: Tactical Long Endurance UAS, http://www.elbitsystems.com/elbitmain/area-in2.asp?parent=3&num=32&num2=32 [Accessed, 20/01/2012].

Finkelstein, N. (2003) Image And Reality Of The Israel-Palestine Conflict, Verso Publications, London.

Galston, W.A. Dumas, L.J. Crocker, D.A. And Townley, C. (2002) The Perils of Preemptive War, School of Public Affairs, Maryland.

Geneva Conventions. (1977) Protocol Additional To The Geneva Conventions Of 12 August 1949, And Relating To The Protection of Victims Of International Armed Conflicts (Protocol I), 8 June 1977, http://www.icrc.org/ihl.nsf/full/470?opendocument [Accessed 26/01/2012].

Graham, S. (2004) Vertical Geopolitics: Baghdad and After, Blackwell Publishing, Oxford.

(2010) Combat Zones That See: Urban Warfare And US Military Technology, In McDonald, F. Hughes, R. And Dodds, K. Observant States, I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd., London, 199-223

GoogleMaps. (2012) Lod to Khiribat Ikhza’a, http://g.co/maps/53a6s [Accessed, 22/01/2012].

Gregory, D. (2004) The Colonial Present: Afghanistan, Palestine and Iraq, Wiley-Blackwell, London.

(2011a) From A View To A Kill, Theory, Culture and Society, 28(7-8), 188-215.

(2011b) Lines of Descent, Open Democracy, http://www.opendemocracy.net/derek-gregory/lines-of-descent [Accessed, 22/01/2010].

(2011c) The Everywhere War, The Geographical Journal, 177(3), 238-250.

Hajjar, L. (2012) Lawfare and Targeted Killing: Developments In The Israeli And US Contexts, Jadaliyya Online, http://www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/4049/lawfare-and-targeted-killing_developments-in-the-i [Accessed, 06/02/2012].

Harraway, D. (1988) Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in feminism And The Privilege of Patial Perspective, Feminist Studies, 14(3), 575-599.

Harvey, D. (2005[1990]) Between Space And Time: Reflections On The Geographical Imagination, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 80(3), 418-434.

Human Rights Watch, (2009) Precisely Wrong: Gaza Civilians Killed By Israeli Drone-Launched Missiles, Human Rights Watch, New York.

Johnson, J. (1981) Just War Tradition And The Restraint Of War: A Moral And Historical Inquiry, Princeton University Press, Princeton.

(2009) Unmanned Aerial Vehicles And The Warfare Of Inequality Management, The Electronic Intifada, http://electronicintifada.net/content/unmanned-aerial-vehicles-and-warfare-inequality-management/8072 [Accessed, 23/01/2012].

Kaplan, R. (2006) Hunting the Taliban in Las Vegas, The Atlantic Monthly, September, http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2006/09/hunting-the-taliban-in-las-vegas/5116/ [Accessed, 20/01/2012].

Ophir, A. Givoni, S. And Hanafi, S. (2009) The Power Of Inclusive Exclusion: Autonomy Of Israeli Rule In The Occupied Palestinian Territories, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Ramsey, P. (2002) The Just War: Force And Political Responsibility, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers INC, Maryland.

Reagan, J. (1996) Just War: Principles And Cases, The Catholic University Of America Press, Washington, 48-68.

Said, E. (2003 [1978]) Orientalism, Penguin Books, London.

Thales, UK. (2012) Reconnaissance Manage Systems: RMS/EMS, Thales Group, Glasgow.

Tozer, T. Grace, D. And Thompson, J. (2000) UAVs and HAPs: Potential Convergence For Military Communications, Military Satellite Communications, 1(3), 24-42.

United Nations Relief and Works Agency. (2009) Direct Hit On UNRWA School Kills Three In Gaza, United Nations Press Release, UN, New York. http://www.unrwa.org/etemplate.php?id=507 [Accessed, 26/01/2012].

Williams, A.J. (2009) A Crisis In Aerial Sovereignty? Considering The Implications Of Recent Military Violations of National Airspace, Area, 42(1), 51-59.

—

Written by: Connor Lattimer

Written at: Royal Holloway, University of London

Written for: Dr. Peter Adey

Date written: February 2012

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Meaning of US Drone Warfare in the War on Terror

- The Bodies of Others: United States Drone Strikes and Biopolitical Racism

- ‘Drone Vision’: Precision Ethics Theory and the Royal Air Force’s use of Drones

- Everyday Insecurity in Gaza: Experiencing Blockade, Displacement and Panopticism

- Old Wine, New Bottles: A Theoretical Analysis of Hybrid Warfare

- The Use of “Remote” Warfare: A Strategy to Limit Loss and Responsibility